White House prayer video sparks a meme parody trend in China. America is the punchline, of course

"Business owners are gathering their employees, forming circles, and jokingly praying for… better sales and higher bonuses?"

The Latest

See all posts“The best casting they could’ve done for this movie”: Fans love Brie Larson as Rosalina due to her extreme Nintendo knowledge

"This is a huge moment for me. I watch these!"

“I need answers”: The “Petsmart Truther” has a viral song about the true meaning of the brand’s name

“Is it Pet Smart or Pet’s Mart?”

“Bloodboiling” leaked texts show Ticketmaster execs bragging about overcharging fans

"These people are so stupid," wrote Baker. "I almost feel bad taking advantage of them."

Fortnite users are calling for boycotts and canceling accounts after new changes to V-Bucks

"We’re raising prices to help pay the bills," Epic Games said.

David protein bars slapped with lawsuit alleging they contain up to 83% more calories than advertised. Macro counters are spiraling

"The David protein bar class action lawsuit hitting NYC gays like a freight train."

Trump says groceries, hotel rates, car prices, and rent are all “way down.” Let’s fact check that

"A president completely untethered to truth," said ex-GOP Congressman Joe Walsh.

“But pet owners DO vote”: Katherine Heigl responds to backlash over her Mar-a-Lago rescue gala appearance

"Animals don’t vote," said Heigl.

Entertainment

Did Kathie Lee Gifford shade the LGBTQ+ community in an interview with Tomi Lahren?

"She's just an old woman trying to keep up with the letters."

“Community” fans point to Donald Glover’s range after he was announced as the voice of Yoshi

"Donald Glover was a COMEDIAN FIRST."

“You guys don’t get it yet”: Fans say Minnie Mouse is in her experimental “artpop era”

"Criss-cross applesauce. Shake it loose, like a boss..."

“Hypocrisy level: infinity”: Director Joseph Kahn calls out “de-gayification of Disney” after Pixar scraps film

"Just say you're scared of backlash and go."

Viral Politics

“Rubiorejo”: Thousands believed a viral story about Marco Rubio’s ears before realizing it was a prank

According to the story, Rubio's cousins once called him "Rubiorejo."

Marco Rubio’s giant shoes have people asking one question: Who bought them?

President Trump reportedly guesses his cabinet members' shoe sizes.

Guerrilla statue of Trump and Epstein recreating the “I’m flying” Titanic scene appears in D.C.

"Make America Safe Again."

The right-wing girlies are fighting! Candace Owens mocks Erika Kirk’s Air Force Academy role, Laura Loomer rushes to defend her

"Since everything is a conspiracy to you, let me explain."

Trending

Denver International Airport seeks gift card donations for TSA agents without pay amid partial shutdown

"It’s a nice sentiment but a MAJOR conflict of interest."

Celebrities jump on the “What were you like in the ’90s” trend

They're all taking a trip down memory lane.

“SUPER unnecessary”: Readers of the “Pretty Little Liars” books just noticed updated pop culture references on Kindle editions

"I wish there was a way to boycott the updated versions."

“Diabolical”: Someone opened their new Star Wars Lego set and found pasta instead of bricks. It’s not an uncommon scam

"There's a Lego set that's really gonna require you to use your noodle."

Culture

“Actions mean consequences”: MAGA traveler who said her politics ruined an Ireland vacation gets lit up on social media

"And I'm not lying to you when I say it instantly went from, 'Yes, I'm American,' to, 'Well, who'd you vote for?'"

“Your AI slop bores me” is the chaotic new anti-AI game people can’t stop playing

Anything AI can do, humans can do better.

“Not even close”: New York’s JFK Jr. lookalike contest drew crowds—and some brutal commentary

"This just looks like every finance bro in Manhattan."

Memes

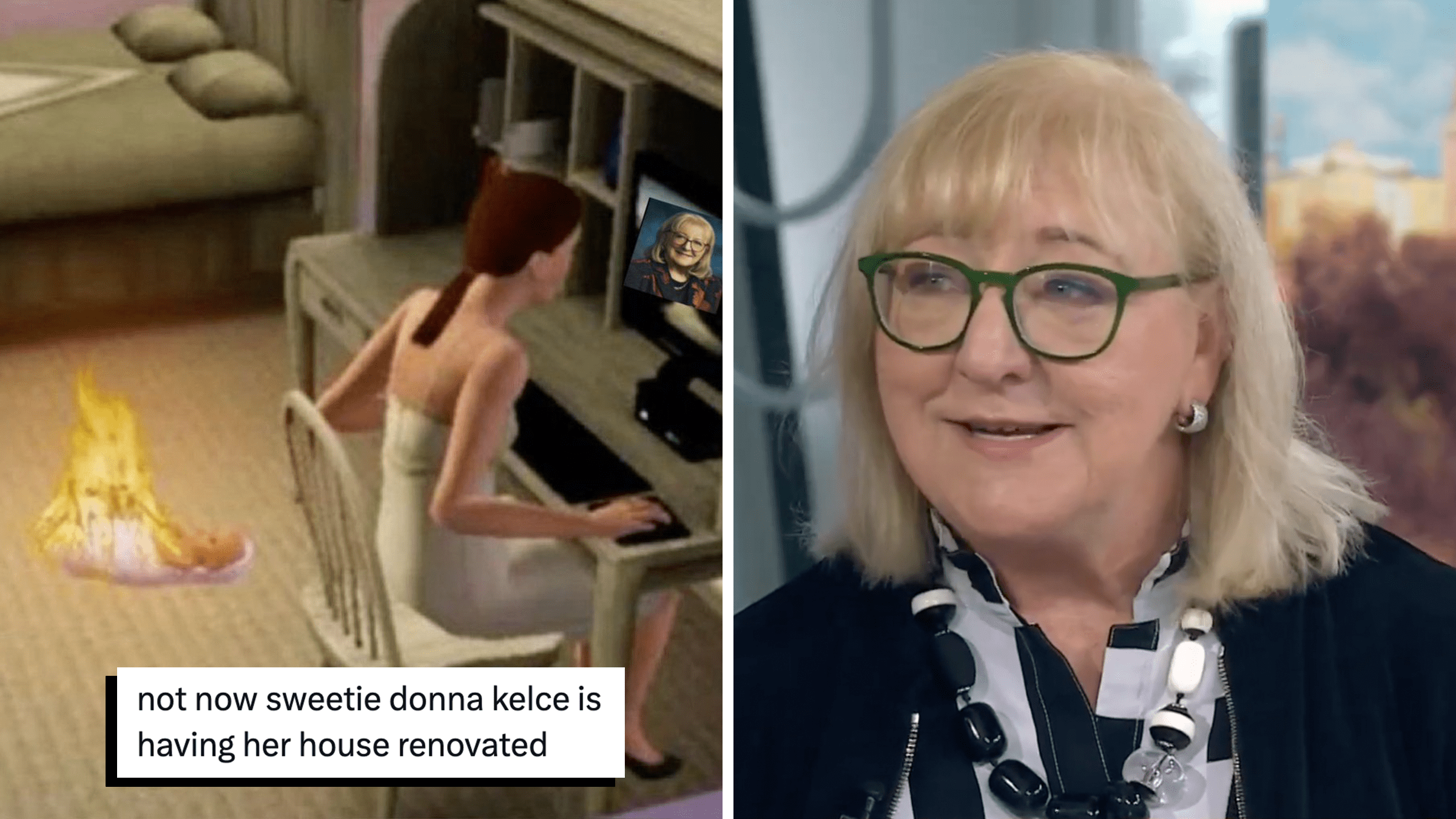

Donna Kelce’s home renovation becomes the meme we needed to face the horrors

"Does anyone have an update on Donna Kelce’s house situation, I’ve been worried about her doors and windows all weekend."

“I thought I was tripping”: Fortnite players spotted a “terrifying” Kim Kardashian skin glitch

Kim K is bugging out.

New “Pokémon Winds and Waves” characters inspire memes and a “Republican” backstory

"Where was Boca Raton Pikachu on January 6th?"

Tyra Banks forcing models to pose with their trauma on “ANTM” inspires the “traumatic photo shoot” meme

"Reality Check: Inside America’s Next Top Model" is the newest meme-maker.

Tech

“You’re gonna make them pay”: A new indie game lets you play as a “Karen”

"The mall denied your refund. Now you’re gonna make them pay."

The next “Stardew Valley” update lets Clint get married, and the fandom is split over the “worst” character’s new upgrade

"I know he's a fixer-upper, but he has a job. And a beard. Which is more than I can say for a lot of these losers."

“Twitch really humbled her”: Doja Cat can’t figure out how to turn off livestream ads after new update

"You can win a Grammy, but you still can't skip the 30-second unskippable ad for insurance. Humbling for the ego!"

This startup says its $1,199 gadget can block listening devices. Skeptics are raising questions

"This would be extraordinary and would require equally extraordinary proof if true."

TikTok

Woman tests how Home Depot workers treat her in a “hot girl” outfit vs dressed “like a boy”

Does pretty privilege apply at the hardware store?

“Ruining the rewards system”: Loyal Starbucks customers were just sorted into three tiers. Some are spiraling about their new status

"I buy Starbucks every day and I’m green so everything is a lie."

“Sounds like a you problem”: American Airlines passenger has a meltdown as she’s booted from plane for watching videos without headphones

"This should be done in buses and subways as well."

Influencer brags her outfit would “cause bankruptcy.” A “thrift god” put it to the test

"Isabel Marant ain't at the bins I fear."