When science fails to cure your child’s cancer you might turn to God, and it might seem like God isn’t listening.

That Dragon, Cancer is an autobiographical indie game about Ryan and Amy Green and their son Joel, who was diagnosed with brain cancer. In the many hours he spent tending to his young son, Ryan began to sense that this cancer was like a game you couldn't really win—and he felt compelled to share the experience in a project that would honor Joel's struggle.

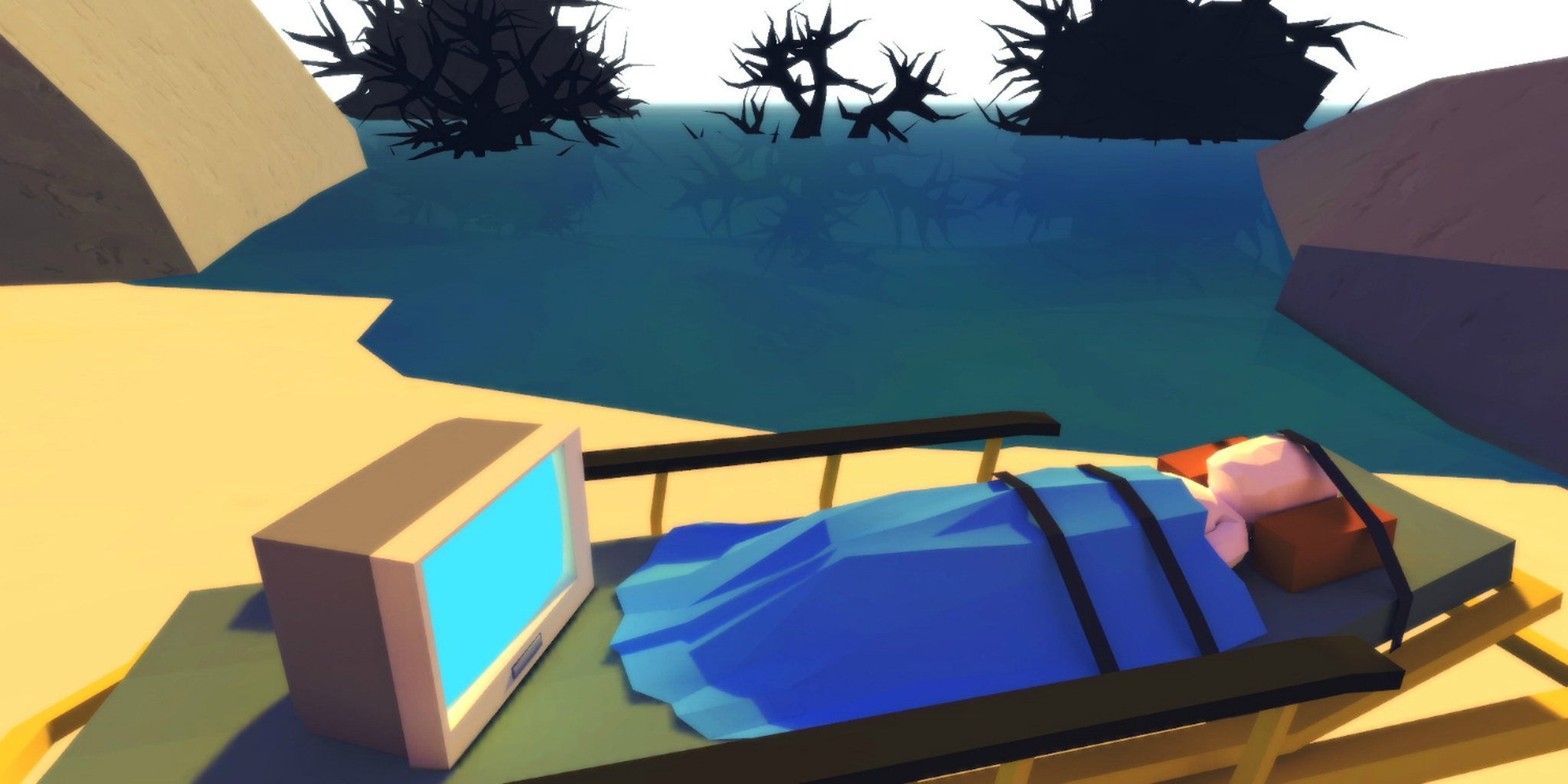

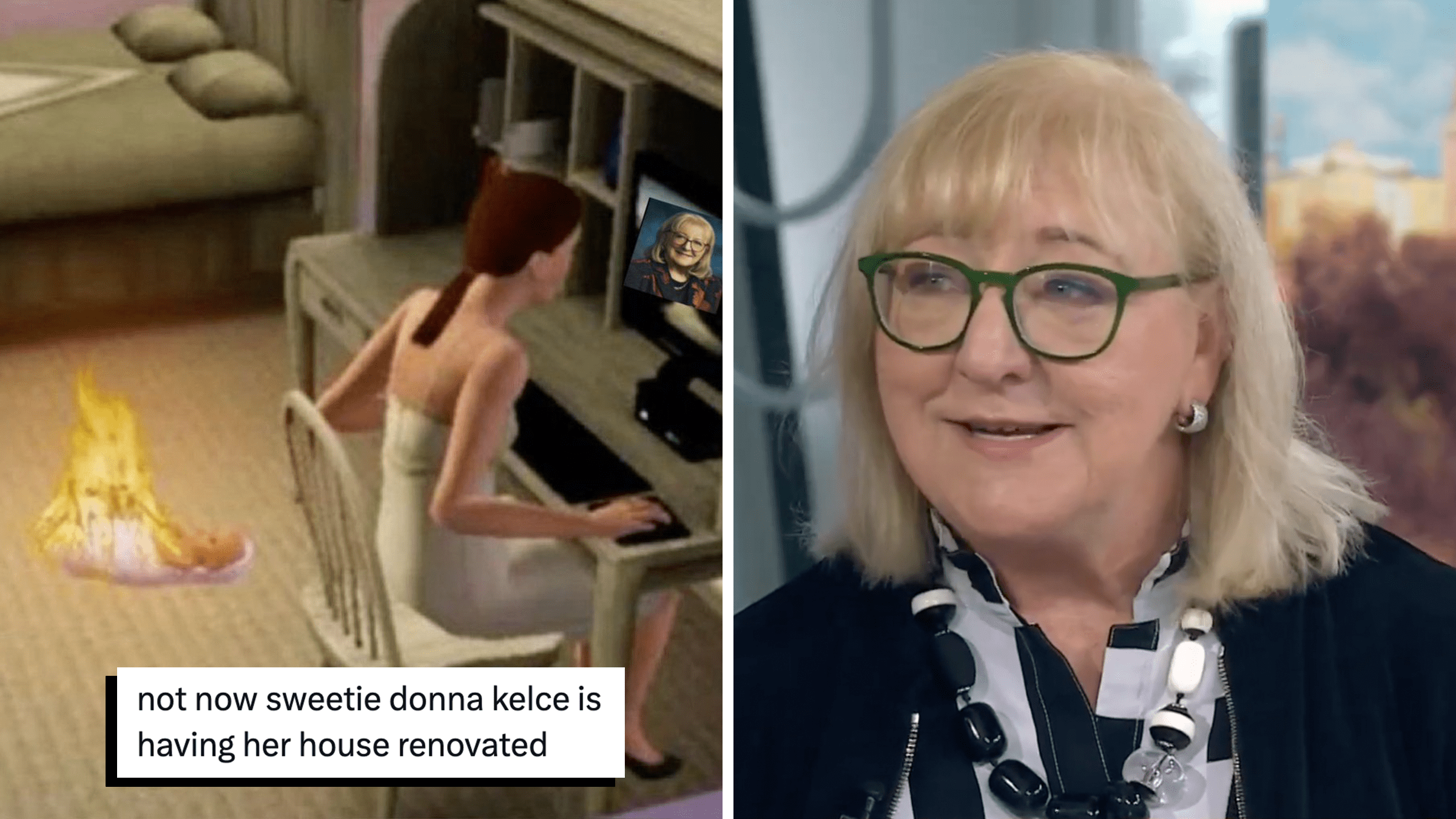

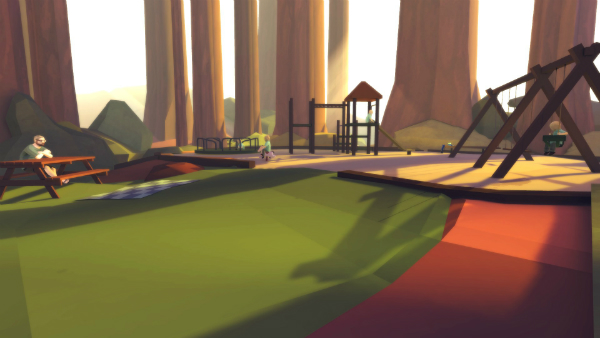

In the game, we first meet Joel as he throws bread crumbs to ducks in a pond while on a picnic with his parents. He is only 2 years old.

The first seven chapters, each of which take the form of a short vignette, illustrate the period in which the Greens treat Joel with a regimen of chemotherapy. This half of the game is filled with images that will be distressingly familiar to anyone who has lost a loved one to cancer or who still has a loved one in treatment.

The remainder of the game is a tale of two Christian parents dealing with a crisis of faith. When science fails to cure their son, they pray to Jesus for a miracle to save Joel. They have to look for comfort in the tenants of their faith when cancer takes him.

The partition between these two halves of the game felts distinct in construction and tone, and encountering that partition was one of the most striking aspects of my experience with That Dragon, Cancer. The game becomes a set of two important and distinct questions. How can any parent deal with losing a child to cancer, and can you ever, truly make peace with such a thing if you have faith in a merciful God?

That Dragon, Cancer

That Dragon, Cancer frequently reminded me of a Terry Gilliam film, particularly Brazil and Time Bandits, in the way space and time are malleable. You may be looking down the hallway of a cancer ward and turn around to discover a wall where there should be more hallway, and then turn around again to discover you’re not in a hospital at all.

First you’re the duck, eating the bread crumbs that Joel is throwing into the water. Then you’re Joel, throwing the bread crumbs, and then you’re walking down a path in the woods. The transitions are never telegraphed. You can never be sure of your surroundings, where the next turn will take you, or when clicking your mouse on the environment will trigger one of these warping moments.

While That Dragon, Cancer borrows its interface from point-and-click adventures, this warping of space and time forces you down paths more definitively than in many adventure games, such that That Dragon, Cancer is more of a guided tour through memories than it is free exploration.

It is during the first chapter—the picnic in the woods—that you’re faced with the first Gilliamesque moment. The Joel you left behind on swingsets and slides is now on the beach, lying on a stretcher next to a heart monitor. Spiky, black blots sit in the water behind Joel, throbbing in time with the beat of Joel’s heart, and the shadow of a dragon passes over the scene.

You have just stepped out of what felt like a depiction of memory to a scene of pure, horrific fantasy. These sorts of seamless, sudden changes in mood and space are layered throughout That Dragon, Cancer, and they are brilliantly executed. The original score for the game is understated and frequently retreats into a minimalist sound design that often felt ominous and unnerving.

Ryan is seated in a chair in a hospital room holding Joel, the sun glowing through the windows. The IV machine behind you beckons with a relentless series of beeps. You naturally turn to face the machine and press some buttons to make the beeping stop. When you turn back around it is night, and Ryan and Joel are no longer in the chair, but sleeping on a couch.

The sudden silence, mixed with the disorientating change in environment, feels alien and disturbing. You never see the transition coming. It’s like a sudden slap to the head. What feels like retellings of actual events blend without warning into dreams.

You were in a cancer ward. Now you are floating through a purple sky with Joel as he hangs below balloons shaped like blown-up surgical gloves. Rows of the spiky, black blots float in the air like a minefield.

The point may have been to keep the player constantly on their toes, to never allow them to feel comfortable or settled in a space. Maybe that bears some resemblance to the challenge of trying to feel any sense of stability or normality when confronted with trying to maintain a family and life while treating your two-year-old for cancer.

That Dragon, Cancer

That Dragon, Cancer is drawn in a minimalist style. Joel’s face is defined by polygons, instead of soft curves. Shapes are drawn with hard lines and the colors don't blend in with one another for the most part. I suspect the simplicity of the graphics is what makes the seamless, shocking transitions possible. When the images are simple, swapping them out with one another isn’t as taxing on the software. It can be done quickly and immediately.

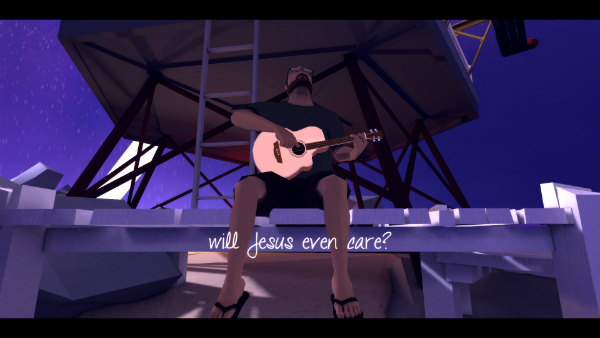

That Dragon, Cancer makes heavy use of subtitles that cannot be turned off. This addresses a quintessential problem with games where music and sound effects can easily cover subtle, quiet dialog. It also illustrates why some people choose to turn off subtitles, because the eye is naturally drawn to them, and they distract from the imagery of the scene. So much of the game is composed of abstract images or fantastical spaces I often wished the words weren’t in the way. At least the first half of That Dragon, Cancer is light on dialogue.

The part of the game that revolves around Joel’s chemotherapy treatment is, of course, still a personal tale, but also an homage to everyone who has faced the horror of cancer.

In one scene that’s set in the cancer ward where Joel was treated, there are cards lining every table, every desk, the seat of every chair, hanging from strings like pennants. I read each and every one—there were 153 in total—because they may have been the same messages written on cards in the real world, pulled into the game. It felt disrespectful not to read them all.

The first half of That Dragon, Cancer makes it clear that Ryan, Amy, and Joel are not alone in their fight. It is a memorial not only to their and Joel’s struggle, but the struggles of everyone they met along the way. It’s this first half of the game that's most likely to tear into you emotionally, for all the touchstones of your own experience with losing a loved one to cancer, experiences that too many of us share.

That Dragon, Cancer

Where the first half of the game is about an experience you may have shared in some way, the second half of That Dragon, Cancer depicts the time in which Joel’s chemotherapy treatment is deemed a failure, and his remaining time on Earth is short. This part of the game is focused squarely and intimately on Ryan and Amy, and how they faced this most horrific of declarations, a doctor pronouncing a timeline as to when they will lose their son.

In their case it was faith in Jesus, God, and belief in Grace that Joel’s parents turned to, and That Dragon, Cancer becomes a very Christian experience complete with references to biblical tales, and overt Christian imagery. The second half of the game is much heavier on the symbolic, and the metaphorical, and less about presenting you with places that could have been real in the physical sense.

The idea of Christian faith and the role that faith plays in the face of crisis for this family are not absent from That Dragon, Cancer prior to this transition, particularly in the scene with the cards in the cancer ward. Statements of belief and entreaties to God appear often.

But the second half of the game is defined by an ongoing discussion about how much faith ought to be placed in God, whether believing in divine intercession is a source of strength or false hope, the anguished desire to demand a miracle, and finally drawing solace from the belief that Joel has taken his place in Heaven.

The line that divides the two halves of the experience may not be obvious or even felt at all by someone who shares the Greens' faith. Struggle in maintaining faith may be a natural part of the experience when a believer is losing a loved one.

Even if you are not religious yourself That Dragon, Cancer may help explain the role that Christianity can play in someone’s life, and the value Christians draw from their belief. That Dragon, Cancer becomes an examination of how the mind of a believer operates and a demonstration that belief is not easy.

Faith can be taxing, but it ultimately may grant peace. If this is a mystery to you, That Dragon, Cancer may help explain it, inasmuch as anything spiritual can ever be explained.

That Dragon, Cancer

The scene from That Dragon, Cancer that broke me down utterly into tears depicted Joel hugging a therapy dog in his room in the cancer ward. The dog is happy. Joel is delighted. It’s a joyful moment, and I felt grateful that Joel was able to have it.

It also made me think about all the times I’ve taken the same experiences—enjoying time outdoors, being with family, having a happy moment with a pet—for granted, and how lucky I am to have time to make up for that. How lucky I am to have time at all. If there’s any message in That Dragon, Cancer that ought to be universal to anyone who plays the game, it’s that time is precious.

5/5

Disclosure: Our Steam copy of That Dragon, Cancer was provided by Numinous Games.

Illustration by That Dragon, Cancer