Ask a Bitcoin aficionado what the point of Bitcoin is and you’ll probably get a long, convoluted answer about frictionless payment networks, pseudonymous monetary transfers, and a hefty dose of libertarian anti-central-bank ideology.

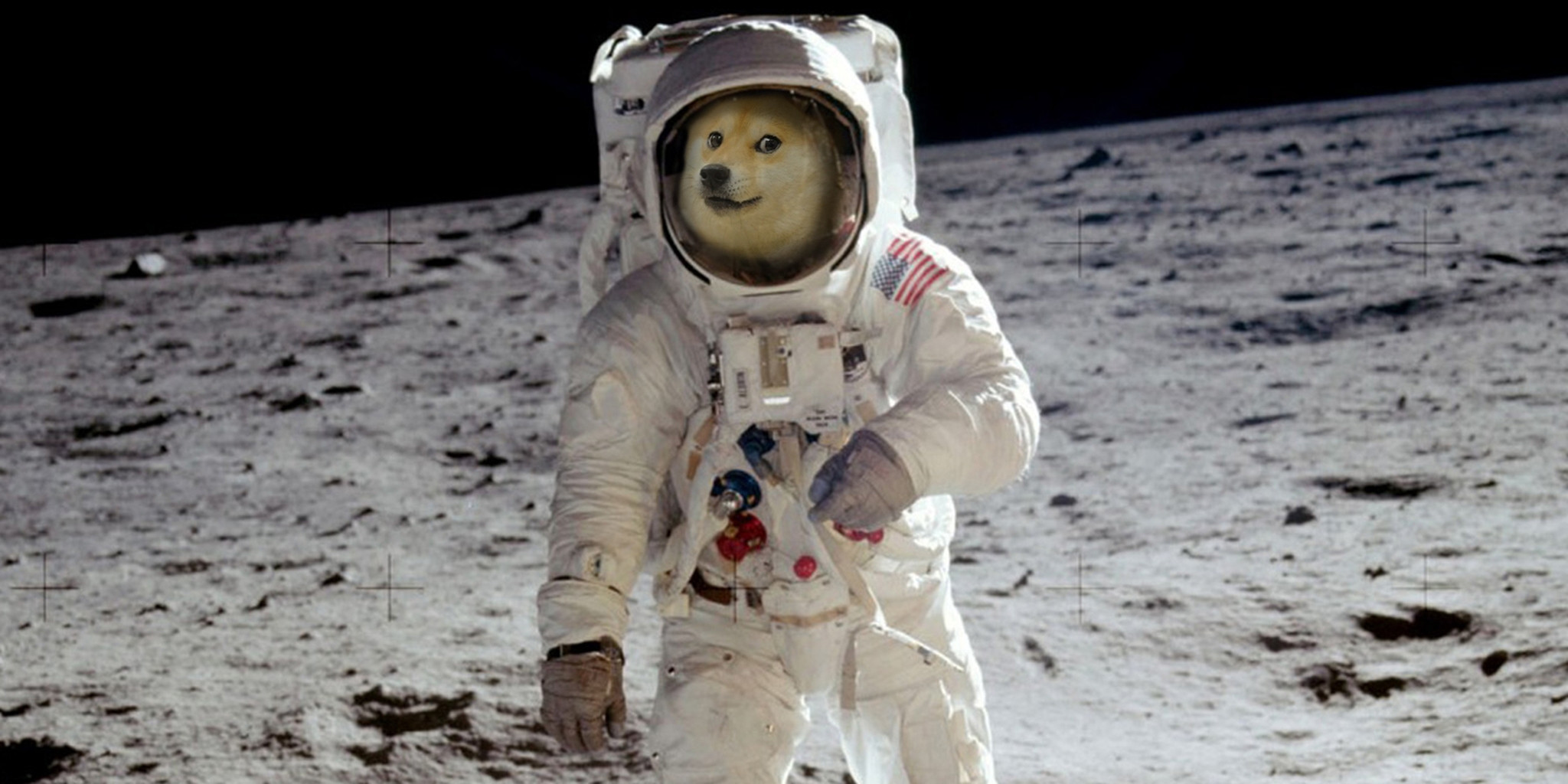

But, ask a Dogecoin booster about the purpose of the meme-themed cryptocurrency that was started as a joke late last year and you’re guaranteed to get one answer and one answer alone: ?TO THE MOON!”

A couple weeks after Dogecoin cocreators Jackson Palmer and Billy Markus first unleashed their cryptocurrency, the value suddenly suddenly jumped by over 300 percent in a 24-hour period. Considering that, even with the increase, a single dogecoin was only worth about $0.00095, Dogecoin users (affectionately termed ?shibes,” after the Shiba Inu breed of dog that serves as the basis for the Doge meme) began ironically stating that each new development would boost the currency onto the lunar surface. It was a phrase originally borrowed from the Bitcoin lexicon, but it really "took off" when Dogecoin's shibes got hold of it.

The irreverent, lighthearted nature of the entire endeavor belies an actual, important question: Just how many dogecoins would it take to actually get to the moon?

…

For some inexplicable reason, representatives from NASA did not respond to a direct inquiry about how many dogecoins it would take to put a shibe on the moon. But there are some figures out there that could, at the very least, provide a rough estimate.

Billionaire Richard Branson’s Virgin Galactic initiative is charging people $250,000 a pop just to get into orbit around the Earth. At the current exchange rate, that’s just under 300 million dogecoins.

There’s one holdup: While Virgin Galactic does accept Bitcoin, it doesn’t take Dogecoin. If an adventurous shibe wants to use dogecoins to get into space, he or she will have to first convert them into either bitcoins or dollars.

Last December, China’s space program landed a lunar rover on the moon. While the total price tag of that moon landing was never made public, the two prior stages of the project totaled about 2.3 billion yuan, or approximately 444 million Doge. It’s safe to assume that the third stage, the one that actually touched down on the moon, went well beyond that.

In 2005, NASA proposed an iniative that aimed at bringing a crew of four astronauts to the moon for as long as a week. The projected cost of that program was $104 billion—the equivalent of over 124 trillion dogecoins. While it doesn’t appear that this idea ever became a reality, NASA did launch an unmanned lunar orbiter to collect data about the moon's atmosphere. That initiative cost about 334 billion Doge.

Governments aren’t the only options for joyrides to the moon, a number of private companies have expressed plans to allow hopeful space cowboys to live out their lunar fantasies. The Golden Spike Company has announced that it intends to sell two seats on a trip to the moon and back for the combined price of $1.55 billion dollars—a figure that translates to about 1.8 trillion dogecoins. If you split it with a friend, each ticket costs 900 billion dogecoins apiece.

Sadly, all of these cost figures for an actual moon landing may be too rich for Dogecoin.

According to CoinMarketCap.com, there are currently just over 61 billion dogecoins in existence. The total market cap is just under $50 million USD. Meaning that, if someone were to collect every dogecoin in the existence and then spend them all on a space flight, the effort would be unsuccessful. Unless, of course, this attempt to corner the Dogecoin market causes the price of a dogecoin to jump 31 times to about 23 cents. In that case, then it would be possible to pay the equivalent of $1.55 billion in dogecoins.

In summation: Unless there are sudden dramatic changes, there are enough dogecoins to make it into space—but not get all the way to the moon.

That is, of course, assuming that the moon hasn't just been a metaphor this whole time. In that case, the 40 million dogecoins donated through the charity Doge4Water, an effort to create a network of wells supplying clean drinking water to the Tana River area of eastern Kenya, likely purchased more than enough rocket fuel to reach the tiny, symbolic moon in all of our hearts.

Illustration by Jason Reed