Everyone knows to never feed the trolls. But what happens when they're part of a government-run online army that has a history of taking their hatred off the Internet and into the streets?

At the Gezi Park Protests of 2013, young people in Turkey gathered in mass, aiming to reclaim not only their last green space from turning into a mall, but also their voice in the country's politics. Their use of social media—Twitter in particular—for gathering and sharing news was a rebuttal to the mainstream media, and it inspired a number of independent news outlets, as well as the video streaming service Periscope.

Turkey’s ruling party, AKP, responded to this challenge by creating a 6,000-member social media team, who were charged with “promoting the party perspective and monitor online discussions.”

The initial plan may have been similar to Vladimir Putin’s trolls in Russia—trolls posing as ordinary people, and using them to promote a positive image of the government on comments sections of news articles. But their challenge got harder when President Recep Tayyip Erdo?an’s corruption network leaked online. Both the president and his trolls resorted to aggressive methods.

First, Erdo?an blocked access to Twitter and YouTube during elections. Since then, his trolls have gotten involved in organizing online lynch mobs against critical journalists, spreading fake news about dissident artists, and even targeting families of fallen soldiers who voiced disapproval of Erdo?an’s security policies.

Lately, the online activities of trolls have taken a dangerous turn. In September, an actual mob, led by an AKP Member of Parliament, gathered around the headquarters of Hürriyet, an opposition paper, smashing its windows and trying to storm its way inside. The MP in question was Abdürrahim Boynukal?n, the head of AKP’s youth branch and the leader of Erdo?an’s trolls.

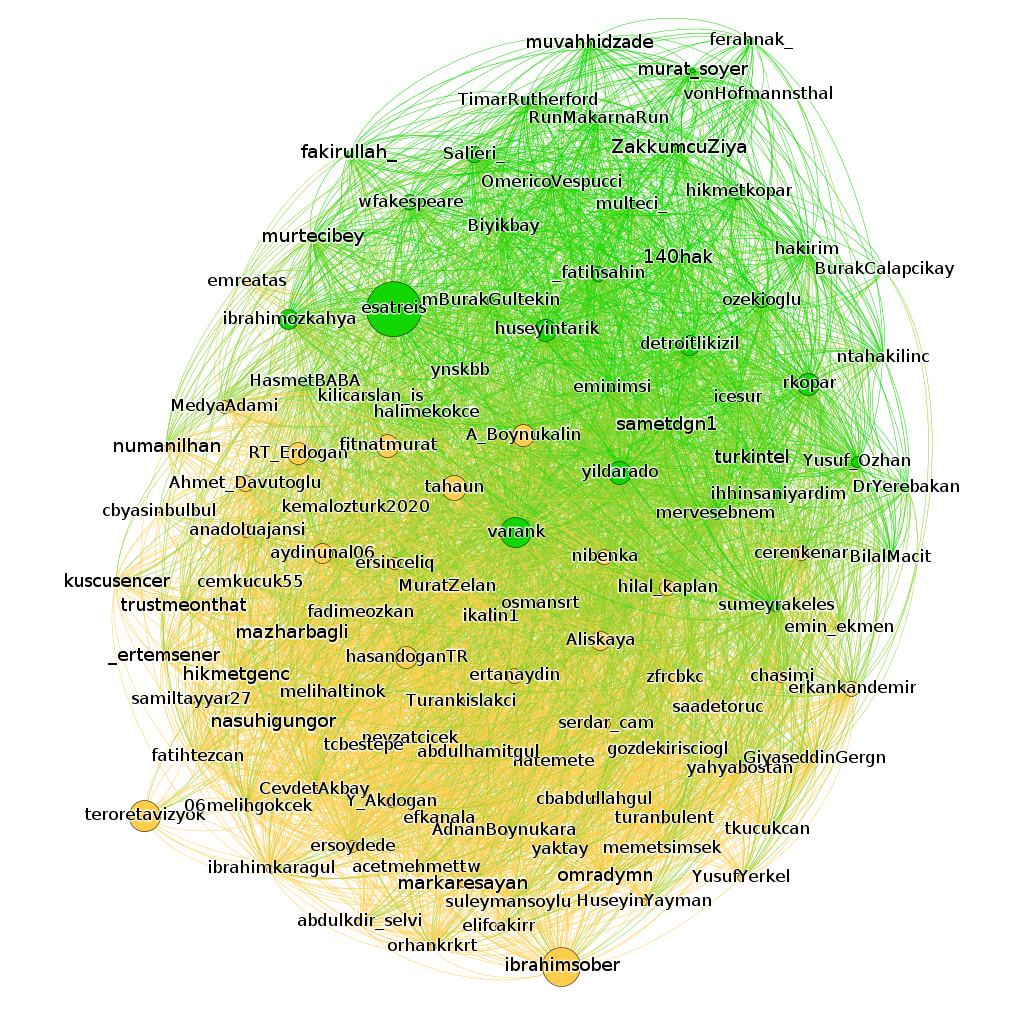

While people have previously drawn links between pro-Erdo?an trolls and AKP cadres, a recent study by an anonymous group of researchers shows the web of connections between them based on Twitter data.

Starting with known troll @esatreis, who was recently revealed to be an AKP youth member, the data identifies the most-followed users in this pro-AKP network and groups them together by the similar accounts they follow.

Broadly speaking, the orange-colored users at the bottom are the AKP officials and pro-AKP columnists who are on Twitter with their real names. Green colored ones are mostly the trolls with fake names.

First and foremost, the map illustrates the AKP clique, composed of politicians, columnists, civil servants, and trolls. But it also identifies the most influential accounts within it: Mustafa @varank, the central figure in the map, is Erdo?an’s adviser. In a leaked recording, Erdo?an’s daughter, Sümeyye Erdo?an, is heard asking him to boost her social media campaign with the help of “AK trolls.” @A_Boynukalin, shown with an orange circle at the center of the troll group, is Boynukal?n himself.

Just like the real-life attackers, these high-profile trolls are in charge of naming targets. On Twitter, this is often done by posting screengrabs of an oppositional account’s tweet (see a recent example). Then, thousands of trolls launch a smear campaign, which often result top-trending hashtags. When a Turkish student was recently targeted online for tweeting about a dead soldier, leading to his eventual arrest, the AKP trolls used this tactic.

This network of trolls also explains why many Turkish celebrities are leaving the platform, citing their weariness at such harassment when they even lightly criticize the government's policies.

Twitter has worked to take down botnets on its platform—swarms of programmed accounts that post automated tweets—that were used for political campaigning. More recently, the company seems to take hate speech and violent threats more seriously as well, going so far as to take down pro-AKP accounts that posted threats against oppositional groups.

But there’s little Turkey can do with the root issue: real groups of people following a few leaders who consolidate them by inciting hatred against others.

Illustration by Max Fleishman