Jamie Duke’s life as she knew it ended three and a half years ago. That’s when her doctor delivered the news that would change everything: She had breast cancer. Her mother had just passed away; now on top of the grief, she was terrified of dying.

The bad times were just beginning. Three months later, the cancer had grown.

From a cattle farm in Louisiana where she’s helping a friend, Duke recalled the doctor telling her that she was nearing stage four with “very aggressive” cancer. (She provided the Daily Dot with records from her cancer diagnosis and a friend who was with her at the time confirmed her account.)

Duke was given two choices: A lumpectomy and radiation or a mastectomy. She opted for a double mastectomy. It wasn’t enough. A month later, her doctor said that without chemotherapy, the cancer was going to spread into her brain and kill her.

Duke was 50 years old with a lot of life ahead of her. But spending hours hooked up to a bag of chemicals wasn’t a life she wanted. So she decided to die.

“Half my body's been burned off. I broke my back. I've had both my legs broken. I'm done. And God makes me suffer all this. I gave up,” Duke told the Daily Dot.

Then a friend told her about a man who claimed to have cured his own cancer with an unlikely and peculiar medication: Animal dewormer, specifically fenbendazole. After looking into it, she decided to give it a try.

Mondays through Wednesdays she took a dose of fenbendazole meant for a large breed dog, Thursdays and Fridays she took ivermectin (another dewormer), she took a few supplements, and she cut out sugar and carbohydrates.

Six months later, Duke said she got the first good news since her diagnosis. The cancer was gone.

Duke’s story is one of hundreds like it. She’s among the thousands of people around the world who believe that fenbendazole cures cancer.

While some are convinced that the animal dewormer is a cure for cancer, others, including physicians, are equally convinced it’s just another snake oil being sold to desperate, sick, and dying people.

Online spaces dedicated to fenbendazole are filled with people critics might charitably call well-intentioned but misguided or cynically accuse of being opportunists capitalizing on suffering. Fenbendazole has not been studied nearly enough for a definitive answer as to whether it cures cancer. Some research indicates it may have potential as a treatment; other research suggests it does not. There are also cautionary tales about the drug damaging internal organs and people getting scammed or dying because they opted for dewormer in lieu of more traditional treatments. Those who believe in its power also tend to be heavily influenced by the undeniable mistrust Americans have in our healthcare system.

No matter how many people claim it cured them, the fact remains that the truth about fenbendazole and cancer is unknown. Some facing the terror of a cancer diagnosis, like Jamie Duke, decide that the benefits of taking a relatively inexpensive, common drug (albeit one that is not approved for humans) outweigh the risks, which for some cancer patients is certain death. Others might conclude that fenbendazole is nothing but hopium, and a potentially deadly one at that.

The man who started it all

Cancer has afflicted humans for thousands of years. The word “cancer” itself has ancient roots: In the fourth or fifth century B.C. the great Greek physician Hippocrates, known as the father of medicine, referred to it as carcinos and carcinoma.

Yet we’ve only been treating cancer for roughly a century and a half. Historically, in the unlikely event it was diagnosed, cancer was simply a death sentence.

Cancer treatment has come a long way since what Scientific American describes as the first “radical mastectomy” in 1882. Breakthroughs have been made and our understanding of the disease has improved exponentially, but despite a thousand promises from politicians, scientists, and pharmaceutical companies, there remains no cure. Five thousand years removed from the first documented evidence of cancer in humans, hundreds of thousands of American lives are cut short by the disease every year.

Chemotherapy and radiation are the most common forms of cancer treatment, but there are thousands of other meds and methods with which people try to cure, prevent, or control the disease. You may not have hooked up to an electronic device or taken a coffee enema, but chances are you or someone you know has aspired to reduce the risk, such as by consuming foods known for their cancer fighting abilities or quitting tobacco.

Still, at some point in our lives, two out of five Americans will receive the dreaded news that they have cancer. For some populations, the rate is even higher.

Eight years ago, Joe Tippens became one of those statistics. Tippens recalled he was days from moving from his native Oklahoma to Zurich, Switzerland when he was diagnosed with small cell lung cancer, a rare and aggressive form of the disease. As he’s written in his blog and repeated innumerable times since, his medical team at MD Anderson Cancer Center immediately targeted the first-sized tumor in his left lung with chemotherapy and radiation.

The side effects were horrific. “They fried my esophagus,” Tippens told the Daily Dot in a recent interview. He couldn’t eat because of the damage but opted against the recommended feeding tube, sending his weight plummeting from 200 to 115 pounds. Clothes and skin hung from his 5’10” frame.

“No studies were published, and we are no longer collecting information on the drug’s use. We cannot offer any medical advice related to it,” the Oklahoma Medical Research Foundation said.

After chemo and radiation, Tippens took a PET (position emission tomography) scan and it “lit up like a Christmas tree.” The treatment had worked on the tumor in his left lung, but the cancer had nevertheless metastasized. There were dozens of tumors, he said, in his stomach, liver, bladder, right lung, pancreas, neck, and tailbone. The American Cancer Society reports that small cell lung cancer that has spread so extensively has a 5-year survival rate of 3%. Tippens, who today is 66, was told he was a dead man walking.

“When you’re told you have cancer, and you're gonna die, you either wilt up and die, or you get busy trying to find a solution,” Tippens said.

He was unmoved. Even as he was being told to get his affairs in order and prepare for hospice, because he had an estimated three months to live, he knew he was going to beat the seemingly impossible odds and survive. “I can't explain why other than I'm wired that way. I was 100% positive I would kick it,” Tippens quipped in his Oklahoman draw, which sounds like a mix of Midwest cowboy and southern. He enrolled in a drug trial for Keytruda, which Merck & Co. was then testing on his type of cancer. He was told it wouldn’t cure him, he said, but could potentially extend his life as much as a year, meaning Tippens might meet the grandson the family was expecting that spring.

Around the same time, Tippens saw that a friend who was a large animal vet had posted on the Oklahoma State University sports board, “If you have cancer or know someone who does, give me a shout.”

Tippens gave him a call and the friend told him a scientist with Merck Animal Health had discovered that fenbendazole kills various forms of cancer in lab mice. On his blog, Tippens wrote that the same scientist was diagnosed with terminal stage four brain cancer, took fenbendazole, and six weeks later was cancer free. The Daily Dot was unable to verify the veracity of this claim. Tippens said the large animal vet has since passed away from heart failure. Merck did not respond to an inquiry.

What is Fenbendazole?

Fenbendazole is a broad spectrum benzimidazole anthelmintic used to treat gastrointestinal parasites such as hookworms, pinworms, and tapeworm. Anthelmintics kill parasites by binding to their nerves and muscle cells and blocking them from transporting glucose, i.e. feeding off the host. Parasites and cancer are similar in a basic sense in that both invade the host, damage its tissues, and absorb its nutrients. Still, fenbendazole is not meant for humans and it certainly isn’t meant to treat cancer.

Tippens, who works in private equity, decided to give it a try anyway. After all, what did he have to lose?

After some research, Tippens came up with the first iteration of what he calls his “protocol”—fenbendazole, curcumin (the main ingredient in turmeric), CBD oil, and vitamin E—and secretly started taking it while on the Keytruda trial.

A few months later he got another PET scan. This time, he says there was no cancer.

“My oncologist was literally stupefied,” he wrote on his blog. He remained in the Keytruda trial but also continued taking his protocol, convinced that the fenbendazole was the cure, and not Keytruda, a cancer drug he says can be a “wonder” for some types of the disease.

His next PET scan was also clear, per Tippens. He says that the doctor told him he was the only patient out of hundreds in the clinical trial, which concluded that month, who had such a remarkably positive response. Due to medical privacy laws, this claim is impossible to verify, but in 2021, Merck withdrew Keytruda as a potential treatment for metastatic small cell lung cancer.

After the second scan, Tippens says he admitted the truth to his doctors. “They just went, ‘Oh [expletive],’ and they just dumped the entire clinical trial because the only survivor in the frickin’ trial was taking something else,” he said.

Tippens says that his radiation oncologist was Dr. Stephen Hahn, who then worked at MD Anderson and later served as the United States commissioner for food and drugs from 2019 to 2021. Medical privacy laws prohibit physicians from discussing patients’ records. Through a company spokesperson, Dr. Hahn, who now works for a venture capital firm focused on life sciences, such as biotechnology, declined to comment about fenbendazole and cancer.

Eventually the tale of the Oklahoman who believed he’d cured his cancer with dog dewormer reached the media. In 2019, local news affiliate KOCO-TV told the story of Tippens’ unlikely recovery.

At the time, Dr. Stephen Prescott, then-president of the Oklahoma Medical Research Foundation, told the outlet, “I'm usually skeptical, and I was and maybe still am about this one. But there's interesting background to this."

Prescott also reportedly acknowledged that other scientists and credible institutions had done work using fenbendazole to treat cancer for years, and said he was working with Tippens to create a case study of people who took it for cancer.

In an emailed statement, the Oklahoma Medical Research Foundation told the Daily Dot, “Led by former OMRF President Dr. Stephen Prescott, scientists at the Oklahoma Medical Research Foundation took initial steps in a review of people who used fenbendazole. Unfortunately, Dr. Prescott passed away from complications from cancer in May 2021, and that work has since ended.”

“No studies were published, and we are no longer collecting information on the drug’s use. We cannot offer any medical advice related to it,” OMRF added. “We are also unaware of any clinical trials using the compound.”

Tippens’ story went massively viral. For some cancer patients, it was a beacon of hope. For others, Tippens says it was an opportunity.

A flurry of coverage and interest followed. Groups and posts started popping up across the web. Today there are thriving online communities of people who believe fenbendazole will cure cancer. Some are acting in good faith; others, according to Tippens, aren’t.

“We have charlatans, crooks, crazy multi-level marketers out there, literally stealing my pictures of me and my kids and my grandkids and saying they're me and posting up false websites selling bad product. It's really scary,” Tippens said.

One man’s miracle, another’s opportunity

Humans are naturally drawn to stories about miracles. A cancer patient making a complete recovery and surviving years after he was told to go home to die certainly falls into that category. Tippens and his claim that fenbendazole cured his cancer had become the stuff of internet legend.

Jamie Duke is one of what Tippens says are thousands of people who believe cancer may have killed her if she hadn’t heard of what’s now known as the Joe Tippens Protocol.

One TikTok about it has 3 million views; several have 100,000 or more. A Telegram group called Fenbendazole and Ivermectin (another dewormer) has nearly 16,000 members.

Facebook appears to be fenbendazole central.

On that platform, the Daily Dot found over 30 groups and pages dedicated to discussing fenbendazole and cancer. Multiple groups have tens of thousands of members. One that launched months after the first coverage of Tippens’ recovery has 100,000 members. Most of these groups describe themselves as offering cancer support and include boilerplate disclaimers that they are not dispensing medical advice.

The groups are rife with fear, despair, and that sweet nectar that eludes many cancer patients: Hope. Alongside testimonials from those who say they were cured, you see comments like “I’m dying and scared,” “I'm not responding to chemo and they say it is terminal so I'm trying this. What is there to lose?” and “Just a big hope scam.” There are also warnings about bad product and scams, and innumerable offers to buy products and services that will supposedly treat or cure cancer. There are also wild, unverified claims that fenbendazole will cure everything from autism to ALS.

Most, though not all, people who post about their cancer in these groups say that they are opting for both traditional treatments like chemotherapy and radiation along with fenbendazole and other “natural” remedies.

For all their disclaimers and rules about not offering medical advice, groups such as these are full of it. A person in one recently inquired about diagnosing and treating skin cancer, prompting people to provide a slew of recommendations that are dubious at best and harmful at worst, such as rubbing cannabis oil, baking soda paste, ivermectin, or various salves on it. Only one person suggested consulting a physician first.

Last February, a member of a group with 100,000 members wrote of feeling depressed and discouraged because despite her efforts, which included taking an enormous dose of fenbendazole (nearly 10 times the amount Tippens and Duke took), along with “all sorts of herbs and vitamins,” baking soda water, and eating organic, her cancer was still growing. The group includes a PDF of its “quick start protocol” that recommends the high dosage Duke describes as “way crazy." The woman said that after five rounds of chemo and radiation on a pancreatic tumor, she’d opted for the natural route and wanted to make sure she wasn’t doing anything wrong.

One of the admins, who describes themselves as a life and wellness coach and “holistic detox specialist” who claims to have cured their own cancer, commented to reassure her that she was doing everything right but also urged her to take yet another supplement.

The woman seemed comforted. “Every one of your comments help,” she wrote. According to an obituary posted on her Facebook page, she died two months later. Comments are now turned off on her post on the fenbendazole page.

These groups aren’t simply for advice and support; some are also businesses.

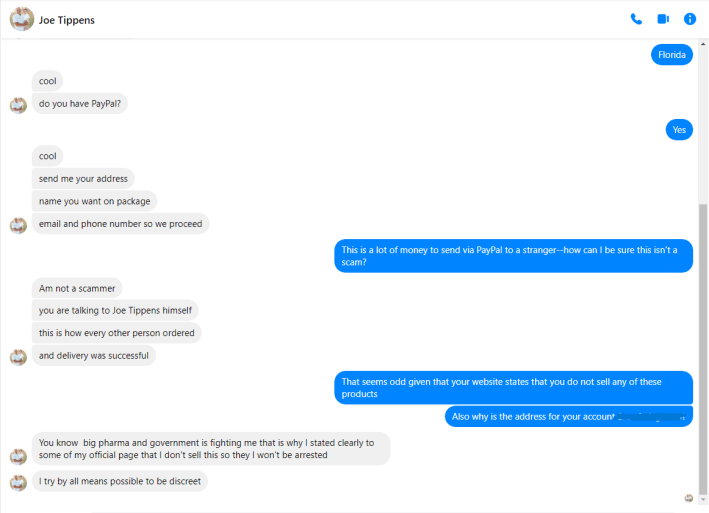

The admin of one group called “Joe Tippens Protocol” recently offered to sell people 90-day supplies of several items, including fenbendazole, “at just $510” and urged anyone interested to DM them. Posing as a buyer, I messaged them to inquire about purchasing the protocol. The person responded that payment could be sent via PayPal and asked for my name, address, email, and phone number. Asked how I could be certain it wasn’t a scam, they replied, “am not a scammer” and said everyone else had ordered the same way.

The admin claims they are actually Joe Tippens, which is their screen name, but the URL of their profile gives a completely different, female name. Still posing as a buyer, I asked about this and they replied that it was because “big pharma and government is fighting me” and they don’t want to be arrested. After informing them they were speaking with a reporter, I again asked why the URL for their page includes a woman’s name, had a woman’s profile picture as recently as last summer, lists their residence as Cameroon, and noted that Tippens, who I contacted via his business website, said they are impersonating him. The person responded, “Anybody saying am not Joe Tippens should proof [sic] themself.”

Then they blocked me from their profile and their group. (A second group blocked me after I submitted a post identifying myself as a journalist.)

Another page that also calls itself Joe Tippens Protocol and claims to be run by Tippens himself sells a dozen products that include those he said he used in addition to several others he didn’t. The cost for all 12 is nearly $1,300. The URL includes “Joe Tippens protocol.” It was registered in April. Whoever runs the Facebook page did not respond to a DM asking if they are impersonating Tippens.

"We have charlatans, crooks, crazy multi-level marketers out there, literally stealing my pictures of me and my kids and my grandkids and saying they're me and posting up false websites selling bad product. It's really scary," Joe Tippens said.

Tippens, who works in finance, insists that he does not sell fenbendazole or anything else related to his protocol, although he’s been told he could make $30,000 a month if he did. “I tell people I'd love to monetize. Thirty thousand dollars a month is not chicken feed. But the minute I do, I'm all of a sudden another guy out selling [expletive] on the internet and trying to make money off of the story.”

Tippens said he’s been trying to get imposters booted off Facebook. He describes being impersonated online as the “typical internet bull [expletive]” he’s had to deal with since becoming a viral phenomenon.

“I've got lawyers involved trying to get Facebook to shut them down because they're really dangerous people,” he said.

“The other fenbendazole alternatives that people are selling are all fraudulent. Every single one of them, I've had them tested. And they're just people trying to make money off of my story,” he added, noting that he fears someone will die from bad product purchased from a scammer. He believes people should only buy Merck’s fenbendazole, which is relatively inexpensive and easily procured online or at various retail locations.

Facebook did not respond to a detailed inquiry about whether either the groups encouraging people to take fenbendazole for cancer or an account that appears to be impersonating Tippens are violating its policies.

Fenbendazole: Miracle cure or a 21st century snake oil?

Much remains unknown about fenbendazole and cancer. Some research does suggest that it or another drug in the same family, benzimidazoles, could potentially fight cancer—though a definitive answer may be years or more away.

A 2013 study of its ability to treat breast cancer in mice reached this somewhat mixed conclusion: “These studies provided no evidence that fenbendazole would have value in cancer therapy, but suggested that this general class of compounds merits further investigation.”

Johns Hopkins University is currently in phase one of a clinical trial testing the efficacy of mebendazole on recurrent, treatment-resistant pediatric brain cancer. (Unlike its sister medication, mebendazole is approved for human consumption.) The trial’s description notes that it is an antiparasitic that “may slow the growth of tumor cells by interfering with cell structure and preventing new tumor blood vessels from forming.”

In a statement, the Food and Drug Administration told the Daily Dot, “The FDA has not approved drug products containing fenbendazole for use in humans. Further, the agency has not approved drug products containing mebendazole for the treatment of pediatric brain tumors.”

“Regarding your question about whether FDA is considering approval of mebendazole, in general, the FDA cannot comment on the existence of any application for approval of a drug that FDA has not approved, or that is pending before the agency, unless the sponsor of the application has disclosed this information.”

Fenbendazole is not without risks and many of the doctors who have publicly spoken about it have issued warnings ranging from dire to simply urging people to consult their physician before downing animal dewormer.

“There is data for fenbendazole in vitro, in petri dishes, but this is not a substitute for clinical trials in humans,” Dr. Amit Garg, an oncologist, says in one TikTok. Dr. Garg warned people against believing “medical misinformation” from the internet and urged them to consult their oncologists before pursuing any course of treatment. Garg did not respond to an emailed request for comment.

In the QAnon Casualties subreddit last year, a redditor who identified themselves as an emergency medicine physician cautioned that they had a patient who put themselves into renal failure with fenbendazole.

Fenbendazole can also cause liver problems. People online have reported developing jaundice while taking it. A 2021 case study in Japan described a woman with nonsmall cell lung cancer who developed a serious liver injury after taking it based on things she read on social media; the injury healed after she stopped taking it.

“Twitter and Facebook are online social media platforms which have been constructively used to exchange information among cancer patients,” the authors wrote. “However, sources of medical information on these platforms are often unproven, and it is difficult for nonmedical professionals to accurately select and filter complex medical information.”

Such warnings may fall on deaf ears for the fenbendazole believers. They tend to fall into three camps: holistic medicine proponents, conspiracy theorists, and cancer patients who’ve either run out of options or, like Jamie Duke, aren’t willing to go through chemotherapy and/or radiation.

They also tend to strongly distrust our medical system.

“This whole country is funded by big pharma. The [expletive] they put in the food here is not allowed in any other country. It's all meant to make you sick. It's called job security,” Duke said bitterly. Cows mooed in the background as she shared that in the last year she switched to the strict carnivore diet Jordan Peterson advocates—with the occasional Coca-Cola as a treat—and that she feels “amazing.”

Tippens, who is also skeptical of big pharma, acknowledges that some people think he’s a quack or a conspiracy theorist. He says he is neither, just a man who had cancer and believes he cured himself and overcame impossible odds with a combination of a dewormer, a few supplements, and positive thinking. He also notes that he is not providing medical advice, simply sharing his story, as is his right.

He claims to have collected thousands of stories from people who say their cancer was cured after taking fenbendazole. In the beginning, Tippens says doctors universally wrote off his story; today he believes some winkingly tell patients that they can’t technically advise them to take fenbendazole for cancer. He opined that there would be more research into whether the drug is effective on cancer—if it was profitable.

“The real reason that nothing's happened with this drug is it's 20 years removed from patent,” he said. “And it would take somewhere between $300 and $400 million to do a proper clinical trial for human consumption. Who in the world is going to spend that kind of money for the next day to have a generic competition? The economics are not there.”

Send Hi-Res story tips and suggestions here.

The internet is chaotic—but we’ll break it down for you in one daily email. Sign up for the Daily Dot’s web_crawlr newsletter here to get the best (and worst) of the internet straight into your inbox.