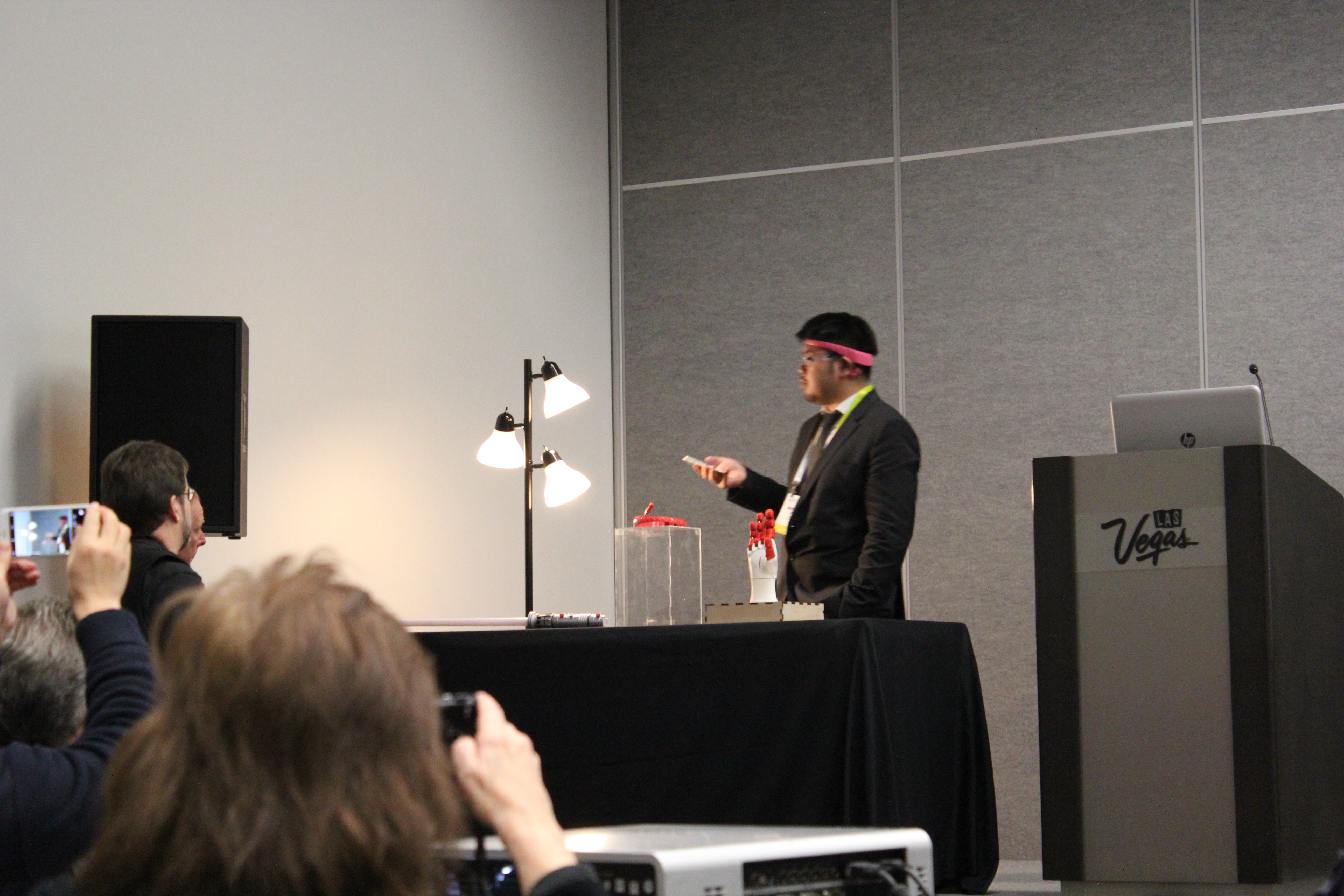

BrainCo seemed set to change the world at the start of its press event at CES 2016. Set in a secluded conference room in the bowels of the convention center, the startup company promised a demonstration of brain-control technology that would allow users to control everything from their lights to a prosthetic hand.

What the device ended up serving as little more than a considerably more complicated means of turning your lights on and off.

The premise of BrainCo's prototyped brain trainer, called the Focus 1, is to create an affordable solution for neurofeedback training—a method of regulating brain function and giving people more control over their brains.

The device uses complex algorithms constructed by students at Harvard and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology to analyze and understand brain waves, which are measured by a single electrode rather than a collection of them scattered across the scalp. Microcontrollers from TI to process the information.

Photo by AJ Dellinger

"I want to know how well people can develop their brain," BrainCo CEO Bicheng Han said. Why? Because, according to Han, "Only 10 percent of our brain is developed. Even the smartest person in the world only uses 30 percent of their brain."

This is a myth that has been busted time and time again, and exists primarily as a premise for sci-fi movies—or apparently to sell people on a mostly faulty product. In 2008, neurologist Barry Gordon at Johns Hopkins School of Medicine told Scientific American, "we use virtually every part of the brain, and that [most of] the brain is active almost all the time."

In its applied form, BrainCo's device becomes a wearable headband that can be used to control household appliances. An accompanying smartphone app displays the results from the band's electroencephalogram (EEG) and helps the user hone their mind to focus more and affect change onto other connected devices.

At the event, the team at BrainCo seemed to have a well-thought-out product, saying all the right things, and even promising to encrypt the transfer of brainwaves from the Focus 1 to the phone. "We are the very first company concerned about the privacy of your brain wave," a company representative said.

Han explained the goal for BrainCo is to remove the phone from the equation entirely and make a direct interaction between device and object. "Your phone shouldn't be in the middle," he said.

This part of BrainCo's product, at the very least, appeared to work. Han equipped the headset and started concentrating on a nearby smart home lighting fixture, which he was able to turn on and off, as well as cycle through colors. A second demonstration had him turn on a lightsaber.

Both of these examples succeeded, though without any real context as to how it all works other than the visual of the companion app. The number displayed on screen, which is generated as a sort of all-encompassing read out of brain activity, rose and the desired action occurred; one would assume correlation between the two activities, but how a person gets the number to increase and decrease other than "think harder" was never really made clear.

Clarity was provided—though for all the wrong reasons—when Han attempted to show off the real potential of the device and control a prosthetic hand.

The application here is obvious, as giving people the ability to control artificial appendages would make it easier to recover the majority of everyday function. Being able to do that with brain power alone would be the ideal solution to the problem because it could be essentially seamless.

This is a goal shared by researchers and medical engineers around the world. There are dozens of universities who have touted progress in the field, as well as a variety of research papers published that foresee an eventual future where brainwaves can control objects.

Unfortunately, the potential didn't pan out in a Vegas conference room. BrainCo's prosthetic hand sat on the table, motionless, no matter how hard the company's CEO thought about wiggling its fingers. It wasn't for lack of effort, either—Han stared down the hand for an agonizing, seemingly endless three minutes, both with and without the companion app active to show his brain activity.

A failed demo is never good, but can be forgivable—especially for a prototype. But what BrainCo experienced rapidly became a degree worse than a simple lack of function.

After Han abandoned the demonstration, setting the Focus 1 down on the table, and walking away, the fingers on the prosthetic hand began to move, interrupting and distracting from the company spokesperson's attempt to rehash details about the device.

That's a mishap that calls into question the overall function of the device. If it's supposedly picking up enough brainwaves when not being worn to control a robotic hand, was it ever actually reading the brainwaves at all? Is the EEG reading entirely arbitrary? Does a person have any actual control over how the interact with objects when using just their brain?

From the rehashing of bad science tropes to the poor explanation of how the device works, BrainCo's presentation didn't leave the few attendants with the impression the Focus 1 was capable of accomplishing what it promised to do.

Even if the headband it could successfully analyze and harness brainwaves, it never appeared like it served much function other than to act as a hands-free on-off switch for connected appliances. That's fine as a start, more complex dials like heating the oven to a certain temperature or setting the microwave would have to be done by hand. Those are tasks that require at least some precision—and controlling a hand would take a lot more than that.

One day, a company might just crack the brain and find a way to control objects with nothing but our thoughts. When that day comes, the reveal for that device probably won't take place on in a makeshift conference room with folding chairs at CES.

Photo by AJ Dellinger