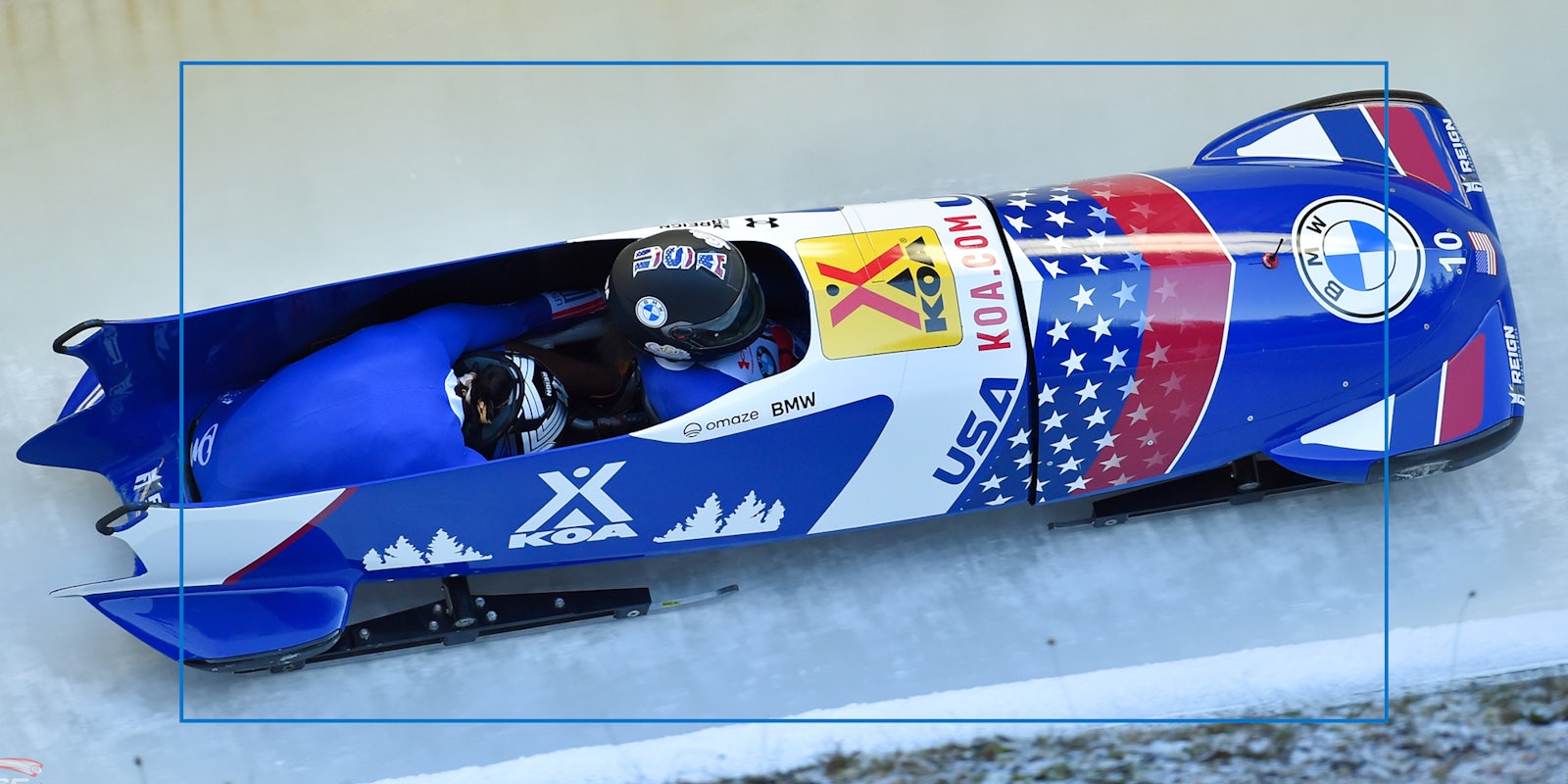

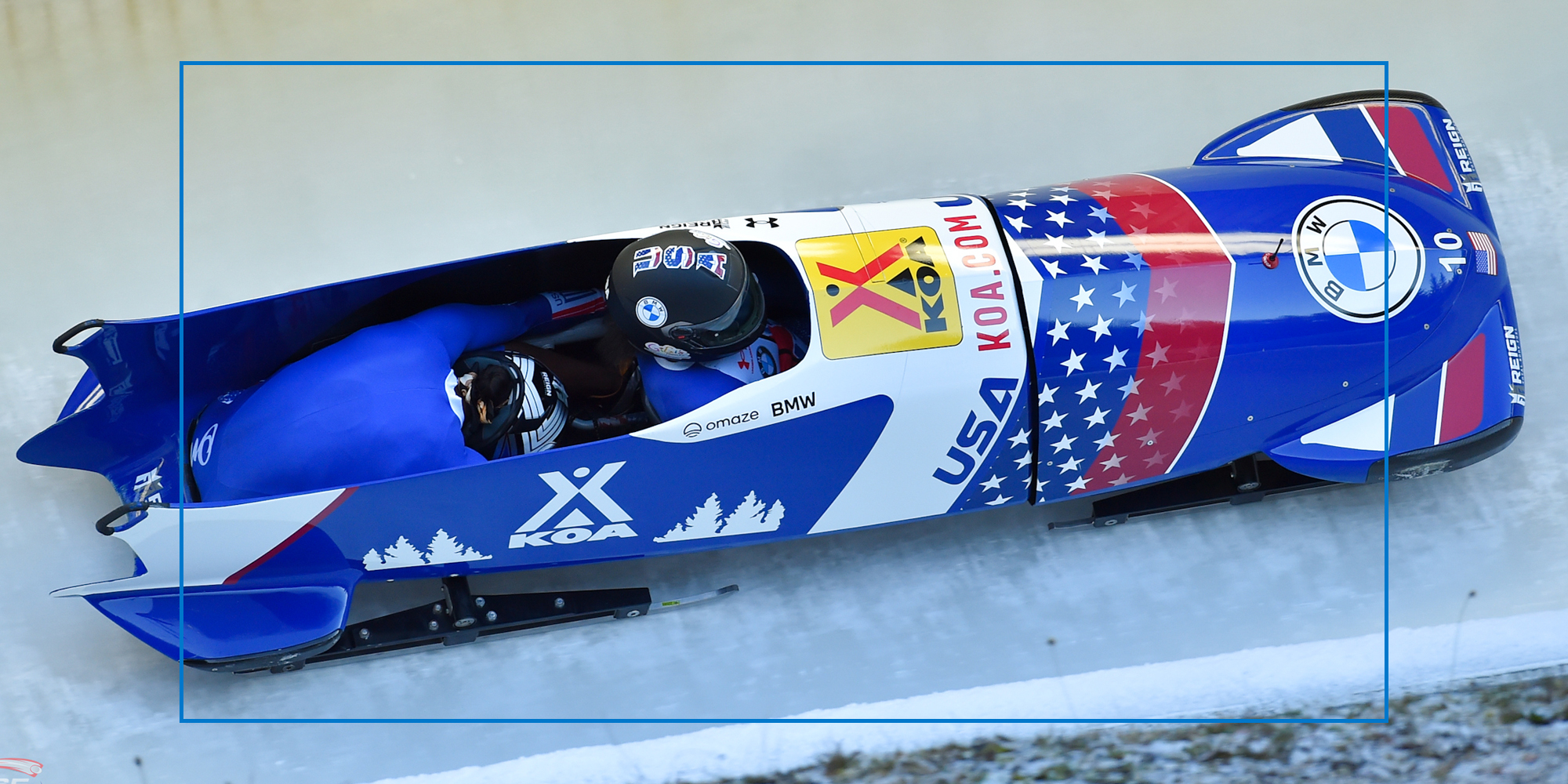

At the start this writing—less than 18 hours after our Zoom interview—bobsledder Elana Meyers Taylor faces yet another challenge. Fortunately, for Team USA and the world, she is an overcomer.

She has been isolated in a Beijing hotel room after she, her husband Nic Taylor, and infant son Nico tested positive for COVID-19. Authorities told the three-time Olympic medalist and two-time world champ that she would require constant testing and consecutive negative tests in back-to-back days before being released from isolation. Heats start in just 10 days for monobob, a single-person event debuting with six other events during the 2022 Winter Olympics.

According to USA Today, her son—who she wants on a podium with her—is two rooms away, staying with her father, former Navy football star Eddie Meyers. Her husband—also her trainer—is biding his time in a room between his wife and their son. Meyers Taylor is still breastfeeding, for which the hotel is assisting in regular bottle delivery to Nico.

Does the 37-year-old athlete—who was vaccinated and boosted—appear concerned? Not especially. The story of Elana Meyers Taylor is an account of significant pivots and overcoming. This is just one more trial in a career full of them.

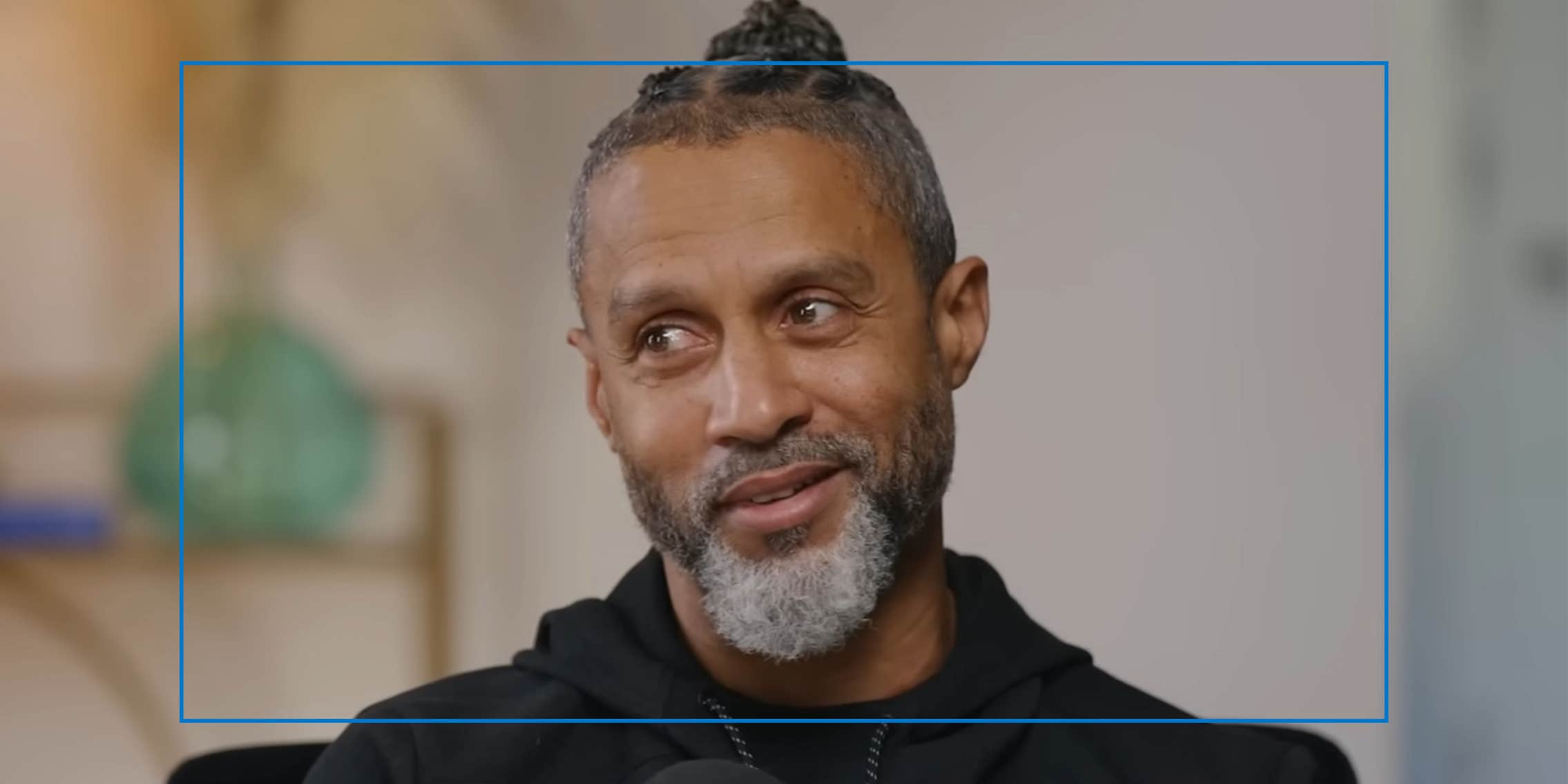

Raised as a talented athlete in the Atlanta metro area, Meyers Taylor was a good softball player at George Washington University as its first-ever signee for the sport. After an up-and-down sporting experience at the university—the softball team was forced to cancel the remainder of its 2004 season, following a 1-5-1 record, due to massive player loss to injury—Meyers received a much-desired tryout for the U.S. softball team. However, in her words, she “crashed and burned.” Her first Olympic dream perished when softball was eliminated from the Olympics following the 2008 summer games—coincidentally in Beijing.

Meyers’ parents advised her to try out for the U.S. bobsled team back in 2002. However, it wasn’t until she retired from professional softball in 2007 that she recalled her parents’ suggestion and found her Olympic calling after a simple email.

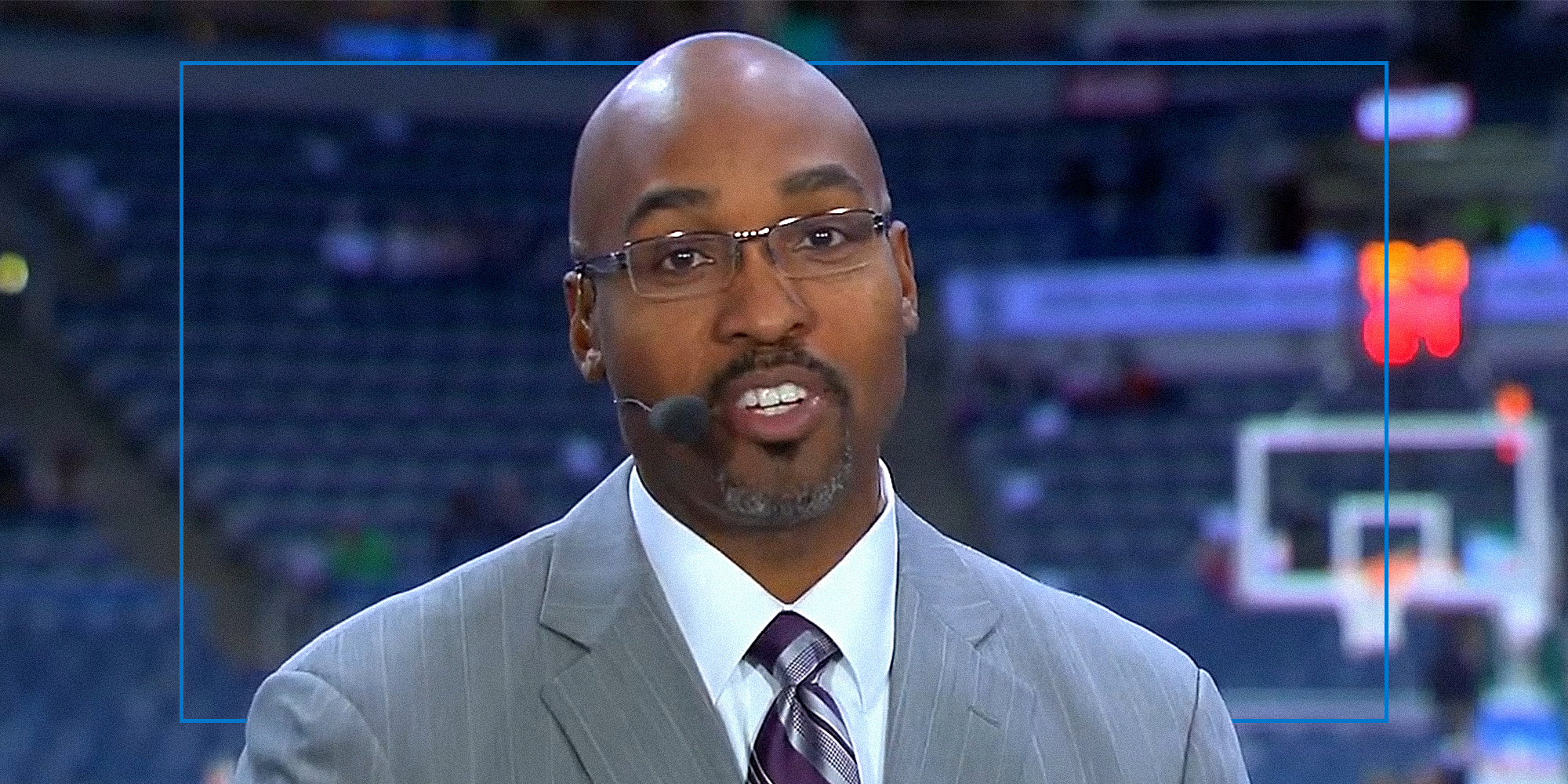

“They invited me to Lake Placid, New York, and I made the national team two weeks later,” Meyers Taylor told Presser. She follows in the footsteps of bobsleigh legend Vonetta Flowers, the first African-American and the first Black athlete from any country to win a gold medal at a Winter Olympics.

Ranked No. 1 in the world in two-woman bobsled and the women’s monobob, Meyers Taylor is now the most decorated American female bobsledder in history: Eight medals (four gold) in the World Championships and three Olympic medals (two silver and a bronze). She and pusher Cherrelle Garrett beat three German crews in 2015 to win the first World Championship in women’s two-person bobsled. She also became the first American driver, of any gender, in 56 years to win a World Championship on a non-North American track. Meyers Taylor also introduced champion hurdler Lolo Jones to the sport. She has also captured two World Championship gold medals—the first came alongside Meyers Taylor at the 2013 games in St. Moritz, Switzerland.

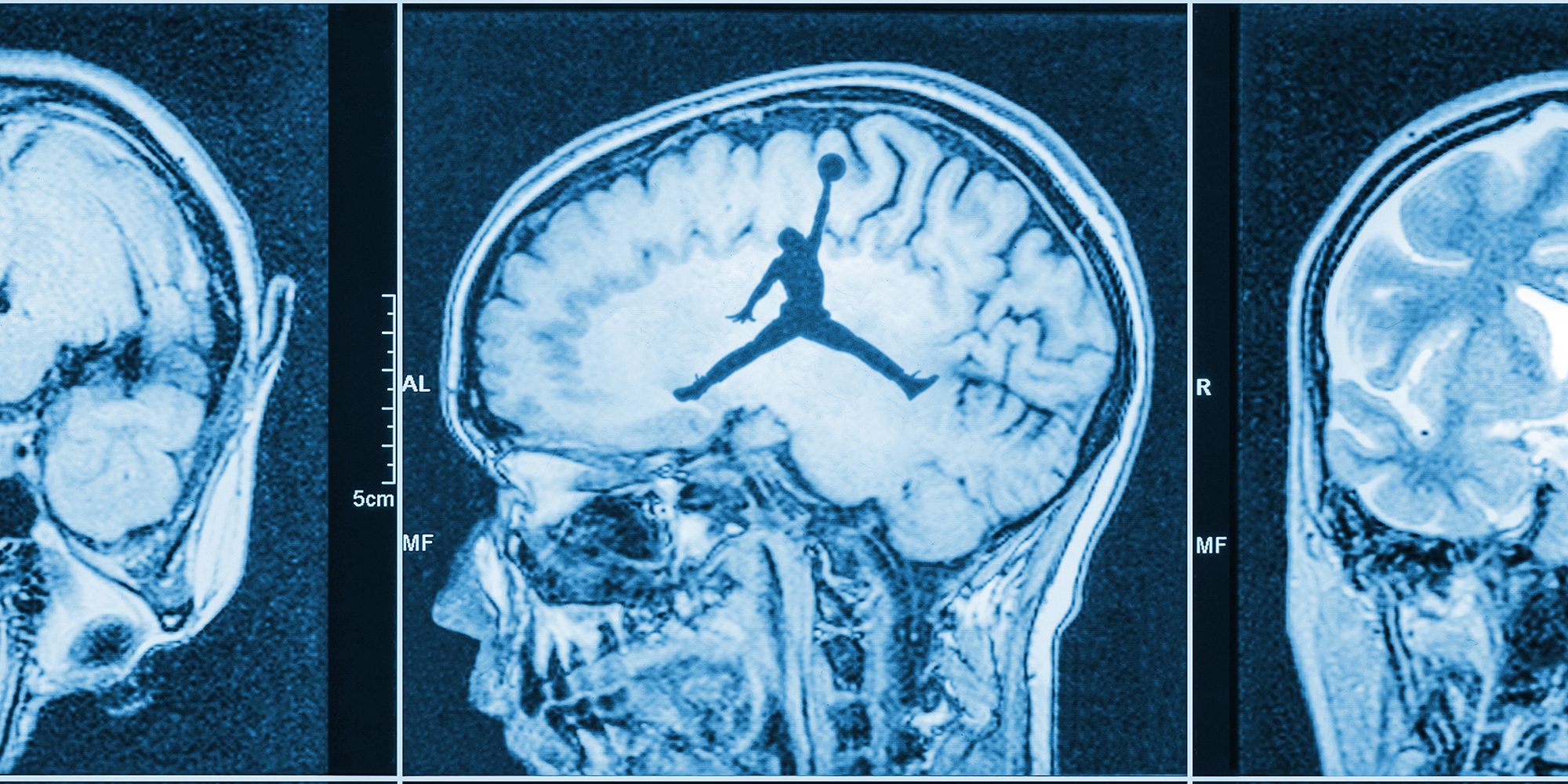

However, much happened in between, and it wasn’t all medals and glory. There have been several concussions. Softball has an underreported history of them, as does bobsledding. Brain specialists who have studied these sled-sport athletes state a unique symptom set that likely stems from a continuous and cyclical series of crashes, headbanging, heavy physical vibrations, and enduring violent gravitational acceleration forces.

Many athletes experience brain fog, even from routine runs with no mishaps, called “sled head.” It’s a problematic term, as it simplifies and normalized concussion or other traumatic brain injury symptoms. Meyers Taylor—who has pledged to donate to her brain for research—candidly describes the sport as someone “being put in a garbage can and kicked down a rocky hill.” After previous concussions, she believes her brain is “even better” following treatment from various brain injury professionals.

“I crash way less,” she said. “I’ve been able to protect myself better. I have safer helmets. I’ve done different things in the sled where I sit in all these different [positions.] We’ve made adjustments over the years to make it as safe as possible.”

The other struggle was Meyers Taylor becoming a leading driver—essentially the pilot, in layman’s terms—the power position in bobsled. Her ascendance wasn’t without racialized controversy—not entirely unlike the idea of a Black quarterback or head coach in the NFL. A driver is a position of intelligence and leadership.

“I was a part of the trend of the sport changing and to get more Black and people of color in the front seat,” recalled Meyers Taylor. “As a driver, you have more control over your destiny. As a brakeman (or pusher) in the back, you don’t have much control over what happens.”

Though there are more Black bobsledders today, including Lolo Jones, the sport hasn’t partaken in a stable history of racial acceptance. According to the Guardian, former British Bobsleigh coach Lee Johnston allegedly told an athlete in 2013 that, “Black drivers do not make good bobsleigh drivers.” In a sport where technology is of the utmost importance, Meyers Taylor said there is at least one leading sled manufacturer that allegedly refuses to sell to Black pilots. They have reportedly been cited declaring, “If I wanted to see a monkey drive a sled, I’d go to the zoo,” according to British bobsled Olympian Andrew Matthews.

She wrote a pointed and passionate piece regarding racism in the sport, pointing out the sins previously listed, among others—including a horrifying police-related story with her husband. She believes she has the gravitas and respect to call out these issues.

“I felt like because of my success, because of my age, because I’m pretty well-respected in the sport, that I have that opportunity to speak up, and because I do have a passion for trying to help athletes as much as possible,” she said.

Additionally, her desire to continue “sliding” comes from a desire to win, accomplish her dream of having her son on the podium with her, and continue showing a Black face in spaces they usually aren’t present. None of it would have been possible without Vonetta Flowers being in the right place and time. Like the adage says, “You have to see it to believe it.”

“I came out to bobsled because I saw Vonetta Flowers, someone who looked like me, and then made it achievable,” explained Meyers Taylor. “If Vonetta didn’t do it, I can’t say that I would’ve. I can’t say my parents would’ve watched if Vonetta wasn’t in it. So I think it’s hugely important for people to see people who look like them. It makes all the difference in the world.”

Elana Meyers Taylor recently gained the consecutive negative tests necessary to compete. Like Vonetta Flowers and many others before her, she will continue the lineage in making the differences that come with being seen by people that look like her.

See more stories from Presser – examining the intersection of race and sports online.