It’s an oversimplification to say that George Floyd’s murder led to soccer players creating an organization called Black Players for Change. But when Floyd was killed by Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin on May 25, 2020, the outrage and the protests that followed touched and galvanized numerous Americans who wanted to make a difference, and were determined that Floyd’s death would not just be another in a far-too-long parade of Black people who have died in police custody, traffic stops, or raids on their homes.

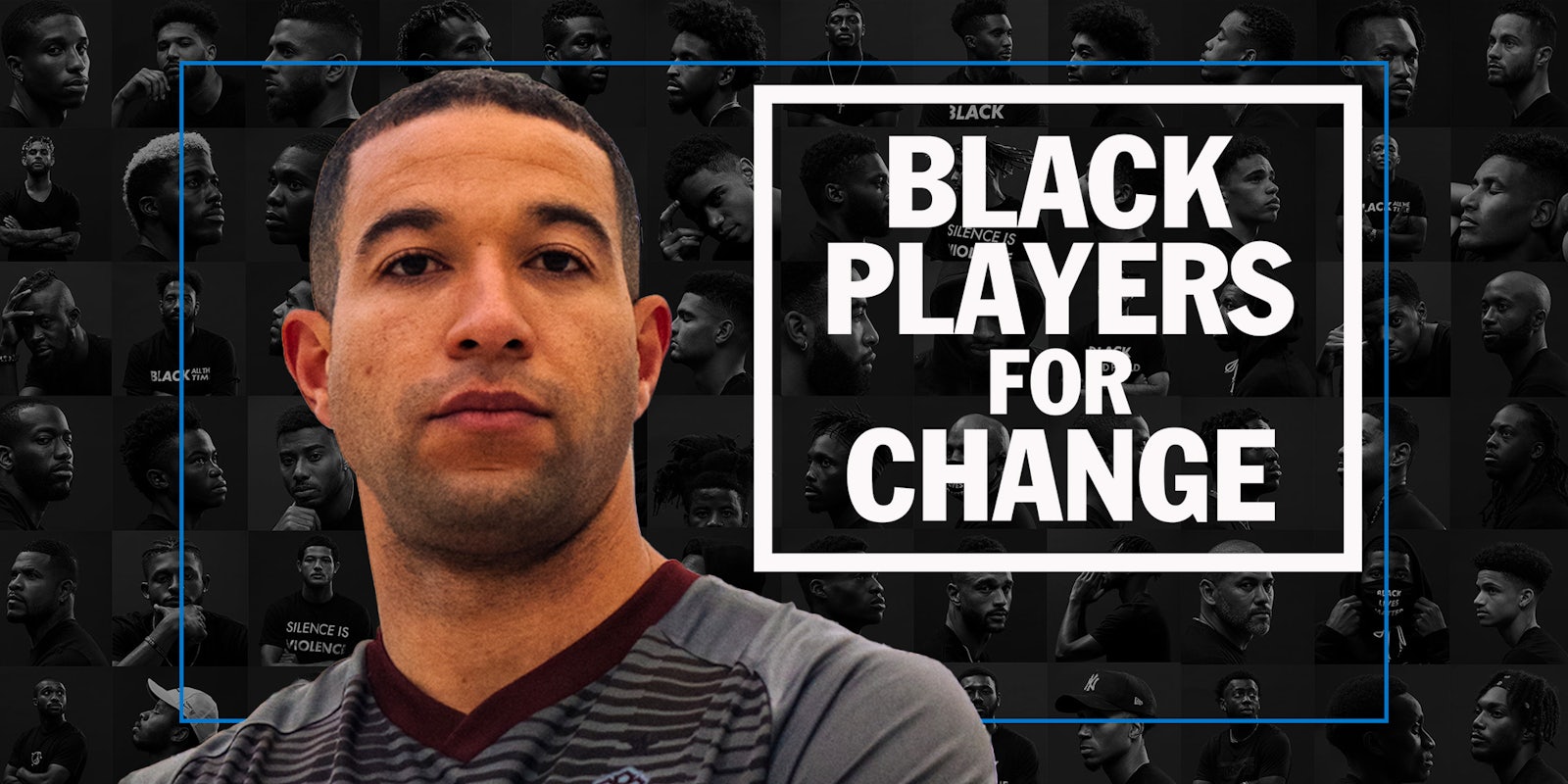

Justin Morrow was among those galvanized. The Cleveland-born soccer player was then in his 12th season in Major League Soccer, the top-flight professional soccer league in North America, playing with Toronto FC—one of just three Canadian teams in a predominantly American organization, launched in 1996 to help the world’s most popular sport take hold in a sports-crazy nation that had been previously reluctant to embrace it.

“We were sitting at home during the pandemic, just like everyone else, like feeling this big range of emotions,” Morrow remembered. “All the uncertainty and the fear, with sickness and everything going on, I think that was a big part of where we ultimately landed.”

While the MLS Players Association had some Black players involved in prior negotiations —including for collective bargaining agreements helping players establish better pay and conditions—some felt left out and even disenfranchised.

For instance, Morrow contends that when FC Cincinnati parted ways with head coach Ron Jans in February 2020, during a league investigation into the Dutch manager’s use of the N-word while singing along to a hip-hop song being played in the locker room, his reputation was already circulating among MLS’ Black players.

“That was something that all the Black players in the league knew about for at least six to seven months before it came to light publicly,” Morrow observed. “The fact that no one even brought that to the Players Association because no one felt comfortable enough to do so, or felt that anyone from the Players Association would support the players in a claim like that, just sheds light on to where we were at mentally,”

Morrow envisioned BPC as an organization specifically supporting Black players. “When the time came, and the opportunity was there for us to organize in an official capacity,” said Morrow, “we all jumped on it.”

BPC, fittingly and intentionally, launched on Juneteenth 2020, when the U.S. was reeling from a COVID-19 pandemic that kept many Americans anchored to their homes for fear of contracting a deadly disease, yet turning out in great numbers in multiple cities to express their outrage over police brutality and for what Black Americans were having to endure.

And then, just weeks after its official launch, BPC—involving 170 Black Players from around the league—got a unique platform in which to make a stance: The MLS Is Back Tournament.

‘Silence is violence’

The 2020 season that started Feb. 29 was paused less than two weeks in, once the pandemic began ramping up and the sports world began halting everything. On June 10, MLS decided to return to play with an ambitious month-long tournament format unlike anything it had attempted before, while most sports were still on pause.

The plan was for all 26 teams to travel to the ESPN Wide World of Sports Complex in the Walt Disney World Resort near Orlando in a format reminiscent of the World Cup and the Euros. Players, coaches, referees, league officials, and team staffers would live in a “bubble” environment, allowing them to control the risk of contracting COVID-19 and get in all their scheduled matches.

Showing how serious it was in maintaining a virus-free ecosystem, two teams with positive tests in their ranks, Nashville SC and FC Dallas, weren’t allowed into the “bubble,” and after a few initial cases recorded in the first week, including one that forced a match to be postponed for a day, the tournament was free of cases from July 16 up until the Aug. 11 finale.

“These fields were set up like television studios or movie studios,” Morrow recalled, “with green screens in the back, cameras and cranes all over the place, microphones on the fields.” Though the environment was surreal for teams used to playing in stadiums that can and typically would hold 20,000, it made BPC members conscious of what was possible to communicate in a broadcast and in social media.

As players from Inter Miami CF and Orlando City SC gathered in the surreal setting for the tournament’s July 8 opener, BPC members ringed the field, wearing black T-shirts emblazoned with slogans like “Silence is Violence,” and held up their fists—reminiscent of the Black Power medal-stand salute from Tommie Smith and John Carlos that, for many, defines the 1968 Summer Olympics.

It lives on in excerpted form in a video shared on MLS’ YouTube channel; in its live unveiling, the demonstration purposefully went for 8 minutes and 46 seconds, the length of time that Chauvin—eventually convicted in April 2021 of Floyd’s murder—pressed his knee against Floyd’s neck, as captured in video by Darnella Frazier to raise awareness around what would become a transformative episode in American history.

The silent, powerful demonstration of solidarity was done in concert with MLS officials, up to and including league commissioner Don Garber.

“The league did a great job in helping us getting it done,” Morrow assessed. “We just wouldn’t have been able to get it done without them. And I think they saw the benefits on both sides of helping us and how it would showcase their league. And I think that they’ve done a great job of coming to the table and trying to work with us, and still do to this day.”

Morrow looks back on that demonstration as “a seminal moment in our organization,” but it wasn’t the only moving display of solidarity with Black people at the tournament. Ray Gaddis, a member of the BPC Executive Committee who played with the Philadelphia Union from 2012 to 2020, worked with fellow Black teammates Warren Creavalle—who designed a Black Lives Matter warmup shirt worn by players and coaches throughout the tournament—and Mark McKenzie to create their own silent demonstration.

Gaddis, who wrote about the MLS Is Back experience for soccer publication Howler, noted in that essay that he, Creavalle, and McKenzie “believe that as black men and professional athletes, we needed to use our platform to amplify a message for the voiceless.” As this clip from ESPN showed, the commentators calling the July 9 morning match quickly realized that all the Union players’ jerseys bore the names of Black people killed by police on their backs—and registered that with a solemn admiration.

Those peoples’ names were also on an armband worn by captain Alejandro Bedoya, who famously was no stranger to taking political stances during matches. Bedoya protested Congress’ inaction on anti-gun violence legislation in August 2019 in a match at D.C. United, by using an on-field mike after he scored a goal to yell, “Hey, Congress! Do something now! End gun violence! Let’s go!”

Gaddis said the Union’s show of solidarity was made more meaningful by players doing their own research to determine who they’d rep on the field. “Every player had to do their homework,” Gaddis noted—in part to prepare for any media who might ask why a player chose a particular person to represent, but also to allow the team to talk and learn and understand the gravity of what was happening.

“It’s one thing for people of color to take a stance, but it’s another thing when you have advocates who are also responding in the best nature that they can,” Gaddis said of his teammates, representing a breadth of nationalities and experiences. While Gaddis noted there was an “outpouring of support” that came to them through social media channels, the most resonant reactions came from family members of the people they memorialized on the field.

“We actually sent them the jerseys we wore,” Gaddis revealed. “Some of the families wanted them to be able to say someone’s still caring about my child, someone’s still caring about this individual that’s loved in this community, somebody’s still advocating and elevating their names.”

‘We stand hand in hand with them’

For Sydney Hunte, an Atlanta-based Black journalist who has been covering matches for the league’s official website since last fall, after starting his soccer writing career at SB Nation’s Dirty South Soccer covering Atlanta United, the tournament felt like a pivotal event to him.

“It’s really interesting to see that play out, not so much how quickly it played out, then that it was just a united front among not just Black players, but non-Black players as well, to see them rally behind folks who have been marginalized, folks that felt that their voices haven’t been heard. Even though they have had opportunities in the league, they’ve looked at it as saying: ‘We’re still facing issues and incidents that maybe white players and white people aren’t.’”

Black Players for Change’s work also involves a national initiative to mini-pitches in a number of cities intended, in part, for Black youths to experience the positives that come from soccer.

The New England Revolution announced the launch of a community improvement fund in July, earmarking funds for BPC’s efforts and featuring Revs player and BPC member Earl Edwards, Jr. prominently in the club’s release.

Last month, Gaddis oversaw the opening of a mini-pitch in his Indianapolis hometown, an effort that included commissioning Black artists to create accompanying murals of groundbreaking Black figures, including entrepreneur Madam C.J. Walker, National Baseball Hall of Famer Oscar Charleston, and World Cup-winning U.S. women’s national team goalkeeper Briana Scurry—to integrate history from past Black achievers into a place where new dreams might begin their ascendancy.

“We want to allow the people who are disenfranchised, but also who don’t have the opportunity and resources to play a game that we grew up with and loved. And there are so many talented African-Americans and people of color that are in neighborhoods that really want to learn about soccer, but they just don’t have the resources, and they don’t have the opportunity, so this is why this is important. It’s part of our objective to lift up other individuals and to reach back, to be that catalyst for change that we want to see in the future.”

The mini-pitch program is also allowing BPC to collaborate with the Black Women’s Player Collective, an analogous group of female players who are currently striving to negotiate a particularly challenging moment for women’s soccer players in the United States.

The premier U.S. women’s soccer league, the NWSL, was rocked recently by allegations that veteran NWSL coach Paul Riley sexually harassed and even sexually coerced players, fueled by an explosive Meg Linehan article in the Athletic. That led to Riley being fired from his North Carolina Courage head coaching post and NWSL commissioner Lisa Baird resigning within 24 hours of the article publishing.

Those shockwaves—including players leading the charge to postpone the first round of matches after the story hit, as well as engineering an on-field, in-match show of solidarity that the league’s social media account tweeted (garnering an incredible 1.6 million views)—highlight the intersectionality of the ecosystems in which all soccer players are working.

“It’s atrocious, the things that those women have had to deal with,” Morrow said of the NWSL situation. “We stand hand in hand with them, support them… because that is just something that we cannot tolerate.

“I think it all it all points to the same thing, that in our systems that we’re dealing with, if we don’t have people in leadership positions that have been a part of it at the lowest levels, that really care about their employees, that care about the environment—these things are just going to continue to happen.”

MLS experienced a similar shockwave moment last August, shortly after the tournament ended and the regular season resumed. Following an incident in which a police officer shot Jacob Blake in Kenosha, Wisconsin on Aug. 23, 2020, MLS players joined NBA players—who had just resumed competition in refusing to play games in protest. Real Salt Lake owner Dell Loy Hansen took to a Salt Lake City radio station—indeed, a station he owned—to assert he felt “disrespected” by the players’ collective action to go on what was effectively a one-day strike.

“It’s taken a lot of wind out of my sails, what effort I want to put into recruiting players and building a great team,” Hansen said toward the end of the interview.

Morrow’s TFC teammate, Jozy Altidore, responded to the news via Twitter, offering to head an ownership group to take the team out of Hansen’s control.

And, to highlight the growing alliance between NBA and MLS players, Utah Jazz star Donovan Mitchell also took to Twitter, declaring his allegiance with Real Salt Lake players.

Then, that very evening, as with the Riley situation, a revealing Athletic story uncovered a history of Hansen’s racist behavior at the club—and the MLSPA took to social media to argue Hansen must sell the team should the allegations bear out.

MLS moved to take ownership of the team from Hansen within days, and its sister NWSL club—also owned by Hansen—was transferred to a Kansas City-based group and moved there in December. The league is still operating RSL deep into the 2021 season, with the team still holding onto one of the Western Conference’s final playoff spots.

Sean Johnson, a BPC executive board member who plays goalkeeper for NYCFC and the U.S. men’s national team—recently called up for World Cup qualifying matches—feels that the action taken in resolving the Hansen situation reflects BPC’s advocacy.

“We wanted to make sure that our voices were heard and that we brought to light what was going on and that it was dealt with, not only in the moment, but what steps are being taken to ensure that things like that didn’t happen again.

“We’ve had conversations with the MLSPA, and they’ve showed their support.” he added. “That’s what we came together as an organization for, to really create that change, and it sparked a whole different level of support that we’re extremely happy and appreciative about.”

Johnson went on to observe that they’ve had conversations with league officials about training and investigations to make sure to limit instances of racial abuse, though to serve as “advocates for accountability,” they’re looking up and down the pyramid of soccer in the U.S., from their own top-tier league all the way to the youth level.

At least one of the BPC principals won’t be in MLS much longer. Morrow announced his retirement from the league several weeks ago, and with TFC enduring an uncharacteristically poor season that started with COVID and Canadian rules forcing them in a temporary Florida home base, TFC likely won’t make the playoffs that start Nov. 20. For Morrow, that means that the Nov. 7 match hosting D.C. United—presenting a final chance to put a goal past fellow executive board member Bill Hamid—will be his last match wearing Toronto’s distinctive red uniform.

But even though Morrow won’t be playing beyond next month, he still plans to be engaged in Black Players for Change leadership and its initiatives.

“Being a part of Black Players for Change has changed my life completely,” Morrow observed. “The amount of stuff that we’ve been able to get done in this short number of months is just incredible, but has felt like a whole life’s work already, a life’s amount of work.

“And so for me, to continue to be able to do that work on whichever level will be so fulfilling, because it’s paramount compared to the stuff that we do on the field or anything else that we can do in life, bringing people together, making this world a better place. There’s just nothing more important than that.”