Analysis

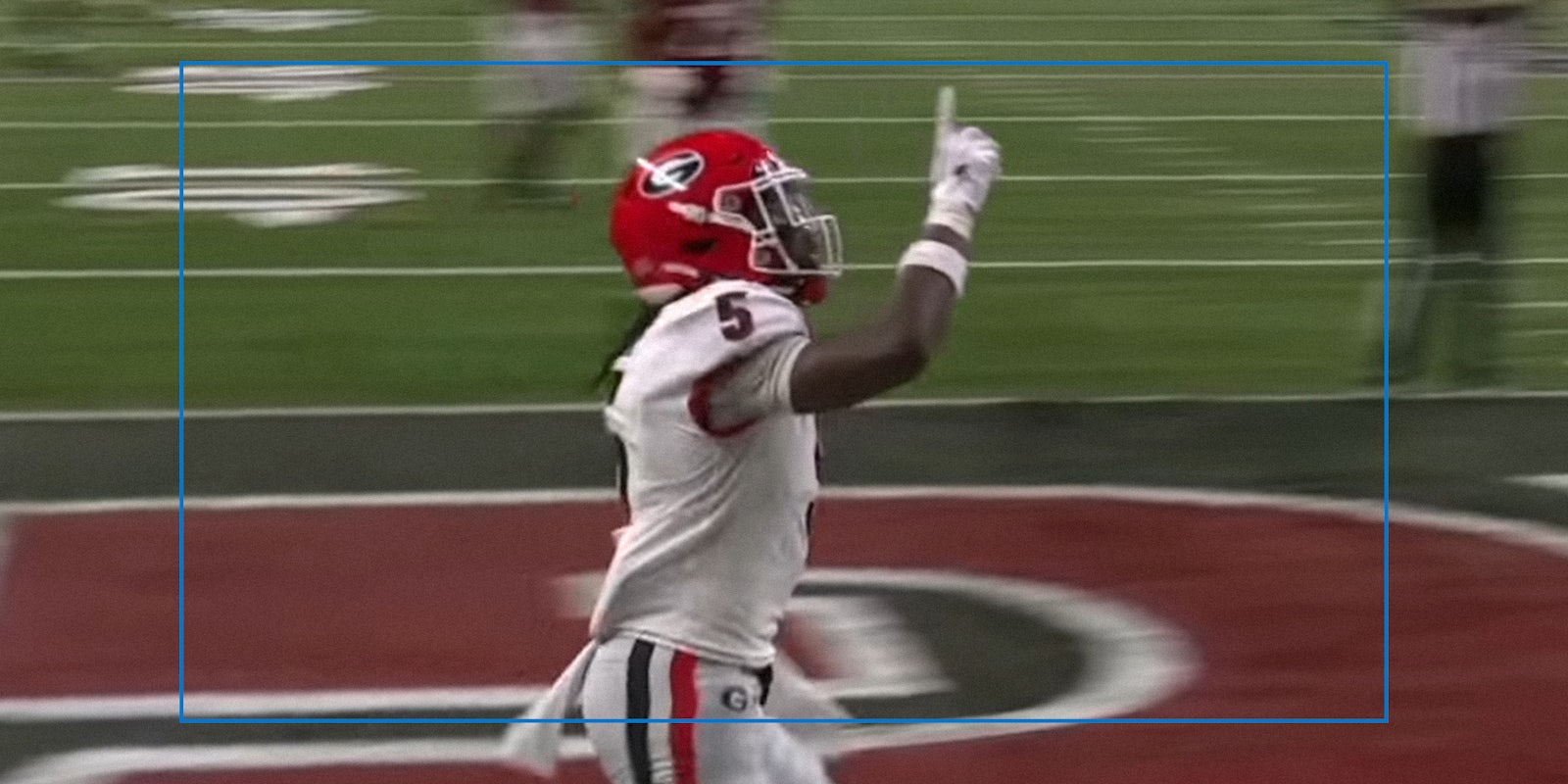

When the University of Georgia Bulldogs proudly lifted the 2022 NCAA College Football Championship trophy high above Lucas Oil Field in Indianapolis, sports broadcasters all over the country hailed the hard work and achievement of the university, its coaches and players. But there was little, if any, coverage of the fact that more than half of UGA’s eligible Black players from the previous season failed to graduate. You’d have to dig deep into peach tree soil to find any sign of a fan concerned with that reality.

The gap in graduation rates between white and Black student-athletes is not a new phenomenon. It remains most pronounced amongst the Power Five Conference football teams in the South. Considering the annual Top 25 polls and bowl game contenders, it’s difficult to see such academic performance numbers and not see a system in which the major D1 schools that put the lowest priority on educating and graduating their Black athletes often enjoy more on-field success than their rivals who push their players harder in the classroom.

In other words, it looks as though allowing young men to fail in their education often results in happy fans come gameday.

Karen Weaver is the academic director of the Collegiate Athletics Certificate Program at the University of Pennsylvania. She reports that studies investigating college football confirm a disregard for low graduation rate amongst student-athletes who are Black—and few resources for those that do graduate but do not go to the professional leagues.

“There are a number of scholars who have collected publicly available data and published reports, written numerous articles in the academic journals and in the general press about this notable and disturbing pattern,” Weaver says. “Of particular concern to me are the athletes of color who graduate without access to additional career planning opportunities, including access to paid internships, mentoring and leadership development.”

College athletes, including many who come from underprivileged backgrounds, are enticed by the opportunity to eventually be drafted into the NFL. The reality is, though, that less than two percent will possess a real shot at professional football. This results in a disproportionate number of Black men without an NFL contract, without a degree and, consequently, potentially without a meaningful professional future.

Richard Lapchick, the director of the Institute for Diversity and Ethics in Sport and president of the Institute for Sport and Social Justice, agrees with Weaver that Black athletes are often poorly served by their college’s sports programs. He attributes this to a history of race and racism in the sport..

“Like America, the sport of football was segregated before the civil rights movement,” Lapchick says. “Barriers began to break for student-athletes in the 1960s and 1970s. For the most part, college coaches recruited and played the best players, irrespective of race.”

Though players may experience equality when it comes to recruitment, there remains a lack of representation when it comes to Black football coaches; the 2021 College Racial and Gender Report Card published by The Institute for Diversity and Ethics in Sport (TIDES) assigned a ‘D’ grade—nearly a failure—when it comes to racial hiring for the head coaches of all Division I men’s football teams. This can be detrimental to the players, who as a result may not have a mentor on the field who shares their experiences.

Year after year, SEC and Southern ACC schools bring up the rear in college football grad rates. A look at the 2018 Black Male Student-Athletes and Racial Inequities in NCAA Division I College Sports Report shows LSU, Georgia, Florida, Arknsas, Kentucky, North Carolina and Ole Miss rank amongst the schools with the lowest graduation percentage; all report rates under 45%.

Still, as they watched the battle for this year’s National Championship, fans of UGA and Alabama were either ignorant of or unconcerned with the reality that the young, Black men wearing their colors on the field could end up out of football, out of school and without career tools. Up in the stands, it’s all about entertainment.

According to Mark Nagel, a professor at the University of South Carolina’s school of Sports and Entertainment Management, it’s important for NCAA schools to make it look as though student-athletes are graduating. He insists, while many fans only care about seeing their teams win, others simply don’t realize the truth behind the scenes.

“The schools want to make it look as if the players are being educated because they’re educational institutions and have a nonprofit status,” Nagel says. “I think anyone who cares about college sports or their individual team wants to believe that players in Division I are there primarily to be a student.”

Nagel believes it’s difficult to blame high-profile student-athletes for failing to focus on education or a potential life without a degree or pro sports income when they and everyone around them dream of a lucrative on-field future.

“The reality for many of these students is that, by the time they’re in seventh or eighth grade, they’ve been told there’s a golden ring waiting for you,” he adds. “That skews what big time college athletics tend to do.”

Back at Penn, Weaver doesn’t see much chance for change that could put degrees in the hands of more underserved Black college athletes.

“With the NCAA defining itself as a ‘member-driven’ organization, and with the College Football Bowl Division controlling the post-season landscape and revenues, little happens that will change anything if schools believe they have to compete against that situation,” Weaver explains. “It’s a classic example of trying to survive in the environment you find yourself in when there are very few times to come up for air.”

Weaver is encouraged that the NCAA does urge schools to develop programs and pathways for athletes who left early for the pros and fell short or had career ending injuries to return to school and get degrees. Many programs have emerged for schools that have the financial resources, with some more or less honoring any given player’s previous scholarship.

“Generally speaking, we still have a long way to go,” Weaver adds.”We need to deal fairly with all athletes, especially athletes of color who dominate the rosters in sports like football, basketball and track.”

We reached out to the NCAA, the University of Georgia, the University of Alabama and Louisiana State University and did not receive a response.

See more stories from Presser – examining the intersection of race and sports online.