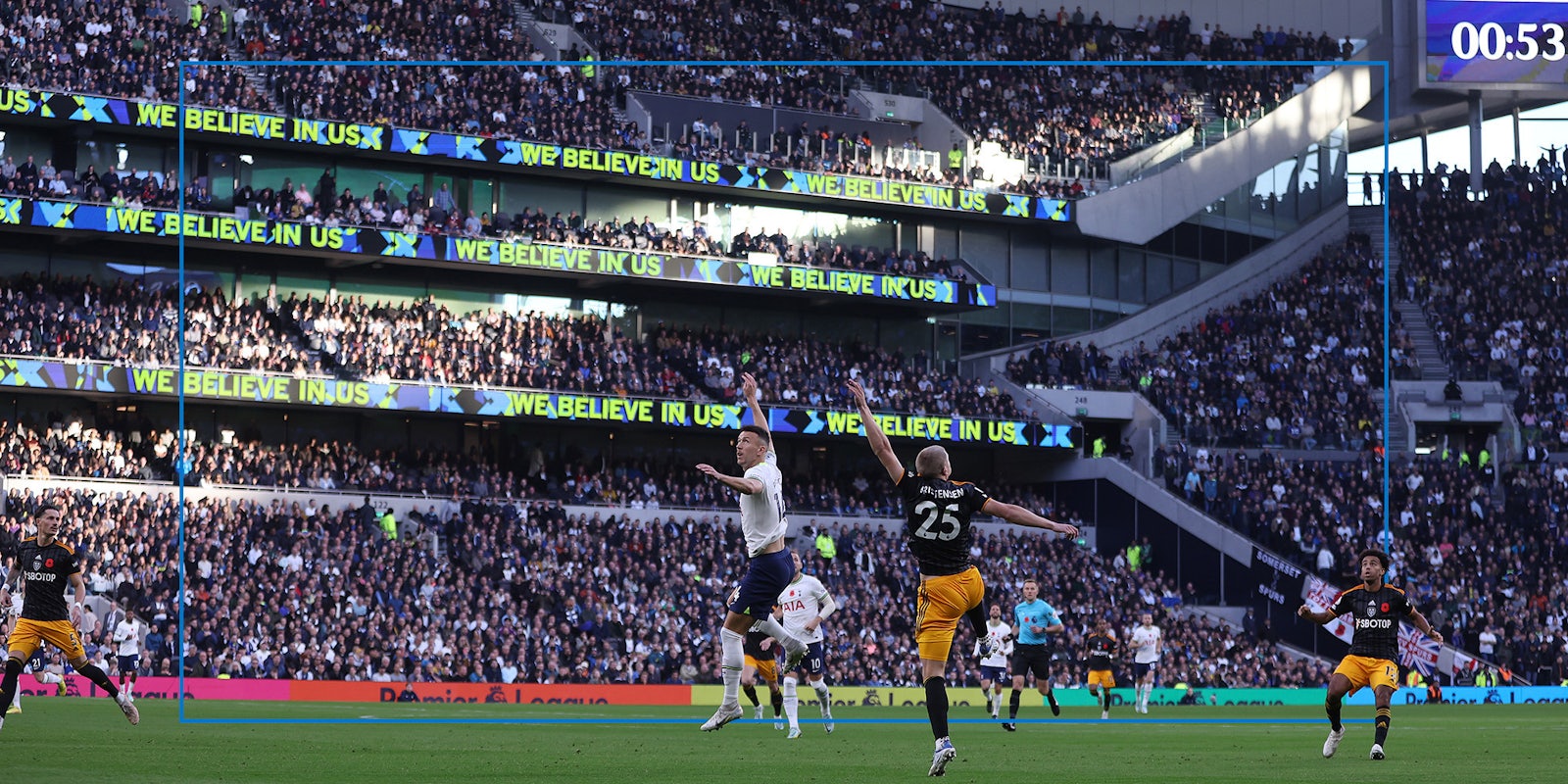

When Tottenham Hotspur fought back to defeat Leeds United on Saturday, Nov. 12 in their Premier League match in London, fans reveled as the final whistle blew. Every screen in the stadium — including the advertising boards ringing the field — flashed with English artist Mark Titchner’s text-based pieces. WE BELIEVE IN US was broadcast live on a Premier League game to millions worldwide to the roar of a capacity crowd. It was an audacious takeover of the space usually reserved for corporate sponsors, the hijacking of advertisement boards to highlight spaces where low and high culture intersect.

The fans jubilantly filtered out of the steel and glass monolith of their team’s home stadium, standing in stark contrast to the deprived north London borough where it is located. Those that entered the official club store, known as the Tottenham Experience, would have noticed that the stadium was forced to be built around a Grade II-listed Georgian townhouse, home to the OOF Gallery.

OOF is a space you enter through the gift shop, dedicated to art and football culture, and where General Director, Eddy Frankel, wishes to “lure football fans into art and sculpture without dumbing it down in any way.”

Frankel, who is London Time Out’s Arts and Culture Editor as well as editor of the print-only OOF magazine — exploring where art and football intersect — determined the space was undoubtedly the next logical step.

He is also a lifelong Tottenham fan.

Fighting ‘snobbism’

“It’s a privilege and a responsibility,” he says of running a gallery frequented mainly by the average football supporter. “We have had great engagement with younger fans. Some dads can’t wait to get to the pub, but if we can convert only 1 in every 1000 passing through, it would be a huge victory.”

With a capacity of around 62,000, the stadium helps attract a considerable footfall that most small and independent galleries could only dream of. It has also had no problem engaging illustrious names from the contemporary art world. David Shrigley, Sarah Lucas, and Corbin Shaw have all displayed work at OOF, and it is currently hosting “It’s The Hope That Keeps Us Here,” the solo show for Titchner, a 2006 Turner Prize nominee who also has work housed in the world-renowned Tate Gallery.

“There’s a huge snobbism towards football in the art world,” says Frankel, “but people are super impressed that we reached so many people. It was a huge win for us.”

Matt S, a boyhood fan and Tottenham Hotspur member of over ten years,(who wished for his full name to be withheld), was on the terraces that day but did not see it. “In the aftermath of a game like that, I’m not sure most people would register,” he says, laughing. “After a match, you’re either angry you lost or buzzing, so what’s going on with the advertising is not the focus point.”

Not that he’s opposed to art on the terraces. “Giving artists a platform is more important than ever, but generally, these messages don’t mean much to me, and I would be surprised if they meant much to others unless they knew the context.”

The 35-year-old, an outspoken voice on online fan forums, where supporters celebrate results but also vent against team performances and the club board, continues his distaste for supporters subjugated to modern forced collectivism.

“As fans, we hold on to an out-of-date notion of what Tottenham is,” adding, “the reality is that the club is a major corporation taking advantage of our lifelong support before it sells up or makes billions from regeneration schemes. Titchner’s work here reminds me of the insincerity of the club’s social media after a defeat. When they post something like ‘WE GO AGAIN,’ it’s the cynical language they adopt to appease us — every club is at it.”

Matt S overheard fans discussing the OOF gallery at the bar in the Bricklayers Arms, a popular pre-match pub for Tottenham fans. As someone who paints in his free time, it piqued his interest. A young gay artist from Birmingham, JJ Guest, had taken over the gallery’s Instagram using the aesthetics of football to explore homoeroticism and homophobia, exploring his discomfort as a fan around other supporters.

Addressing ‘toxically masculine environments’

“I like his work.” Matt says, “Football clubs are considered toxically masculine environments. And they were, especially back in the ‘80s and ‘90s, but that energy is changing. I think this young and diverse England team repping our country dovetails nicely with what Tottenham seems to be going for here.”

The current England national football team has gone a long way in banishing the image of supporters chanting “Two World Wars and one World Cup, doodah!” and burning their rivals’ flags. They are a modern team from mixed backgrounds, shorn of arrogance, and demonstrate a togetherness that previous generations lacked.

Marcus Rashford took to Twitter during the global pandemic to ensure no child in need went hungry. Going head to head with the Conservative government, he won. Harry Kane and Jude Bellingham have championed the LGBT community openly by wearing gay pride armbands and in their social media accounts — but are yet to make a significant stand against Qatar and its draconian stance on gay rights at this year’s World Cup. When Bukayo Saka, a young man of African descent, suffered severe online racial abuse for missing a penalty at the Euros in 2020, he was lifted by a nation’s outpouring of love. Even as an Arsenal player, he was applauded at Tottenham’s home ground by Arsenal’s fiercest rivals.

They are all present at the upheaval of this year’s World Cup held in Qatar. The competition has outraged anyone who believes that human rights are universal.

“Footballers are generally left-leaning and progressive, and many must have skin in the game.” JJ Guest tells me, “but this World Cup has given us the impression that they have been bought.”

‘I want the average man to speak to me’

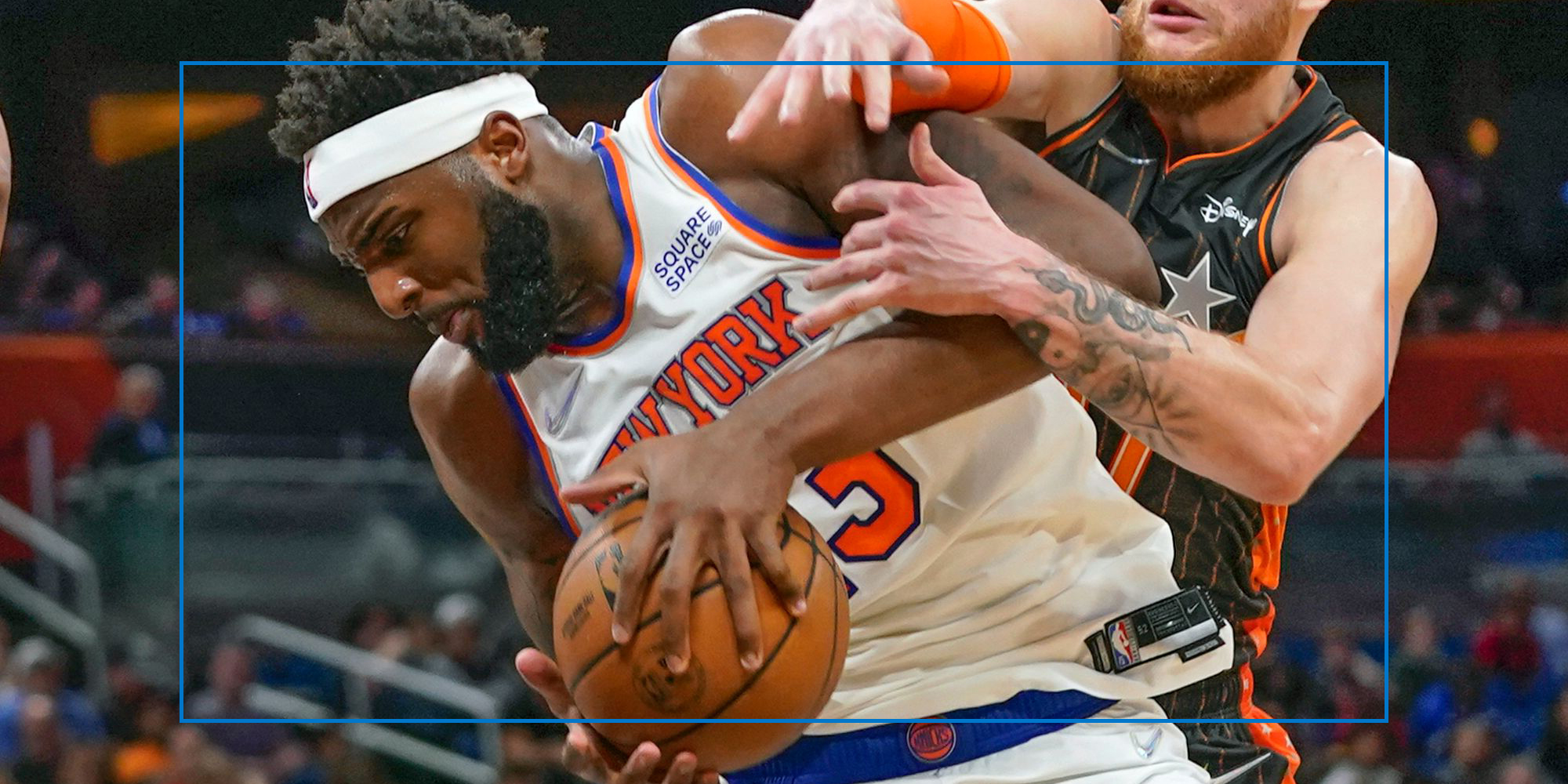

Fathers and sons have always been able to rely on football as the alternative language to talk together about their hopes, disappointments, and dreams. It is where strangers have always hugged and kissed without fear, but Guest’s work tackles the bigotry encountered in a match-day atmosphere. It also zeroes in on male desire, suppression, and repression. That men can hug and kiss in ecstasy on a pitch but can’t hold hands in the stands is reflected in his images of players openly grabbing each other’s genitals at corners or collages of tender moments shared by shirtless men.

“My work is not overtly sexual because I want the average man to speak to me,” Guest says of the dialogue he is creating with football fans who his work may confront. “The conversation usually starts with the kind of burly men that scared me as a kid, and by the end, they start to uncross their arms — I find that power surrendered is longer lasting than power demanded.”

Frankel continues supporting Guest with a studio residency at the OOF gallery and provides studios for local artists. Reaching out to the local community, he encourages school visits that should affect OOF gallery’s survey figures. Ninety-eight percent of visitors asked had never been to a contemporary art show.

“I’m a football fan, but I also know art is more than just pretty pictures on the wall,” Matt S says. “If an artist reaches people who don’t have an outlet to create these messages themselves, it can only be a good thing.”

Guest, an artist who “began on the internet” and who owes his career to social media, is aware of the irony that he has now created “a safe space for straight men to have these conversations.”

It is online and in spaces like the OOF gallery where the battle takes place to shape feverish minds, from Sheffield-born Corbin Shaw’s stark portrayal of hyper-masculine working-class men to Guest’s striking content that challenges hegemonic masculinity. The raw truth within the beautiful game could not be in safer hands.

Frank L’Opez is a Marseille-based Londoner who travels to eat goat, float in bodies of water and find things to write about.

This story is part of the Pixel Pitch series, exploring the spaces where soccer, the internet and identity intersect. Pixel Pitch is a joint project partnering The Daily Dot with The Striker, a soccer-centric online publication “where every day is a soccer news day.”

See more stories from Presser – examining the intersection of race and sports online.