It’s 2001, the new millennium is just getting its sea legs, and both hip-hop and basketball are attempting to do the same. Leaving behind what would become known as a golden era for both the genre and the sport, it became evident reinvention would be key.

For basketball, the answer was a simple one, yet not one that management was ready to embrace: NBA MVP Allen Iverson. For hip-hop, the need for change led to an embrace of corporate interests that increasingly attempted to water it down. In the middle ground of these two entities existed an opportunity to come together for a brief moment on a mainstream scale: The commercial for Allen Iversion’s 6th signature shoe, Reebok the Answer 5.

Despite the overlap of basketball and hip-hop in Black culture, the NBA kept its distance from the genre. That line of thinking was embodied by Commissioner David Stern. Stern became commissioner of the league in 1984, while hip-hop was still in its infancy—and the same year the NBA would welcome its brightest star ever, Michael Jordan. With Jordan as the face of the association, Stern enjoyed unprecedented amounts of success throughout the ‘90s. This resulted in the highest television ratings the NBA has ever seen.

By the early 2000s, Jordan had retired for the second time and those numbers were not holding up, with the exception of the 2001 Finals which featured none other than league MVP himself, Allen Iverson. The impact of Iverson on pop culture during this period cannot be overstated.

“AI had an irreplaceable mark on culture and sports when I was coming up,” Jasmine L. Watkins, head of content at Buzzer and host of the sports podcast You Late, tells Presser. “He solidified what cool looked like both on and off the court. From the pregame fits to the way he played the game. Arguably top five when it comes to the mark made on history.”

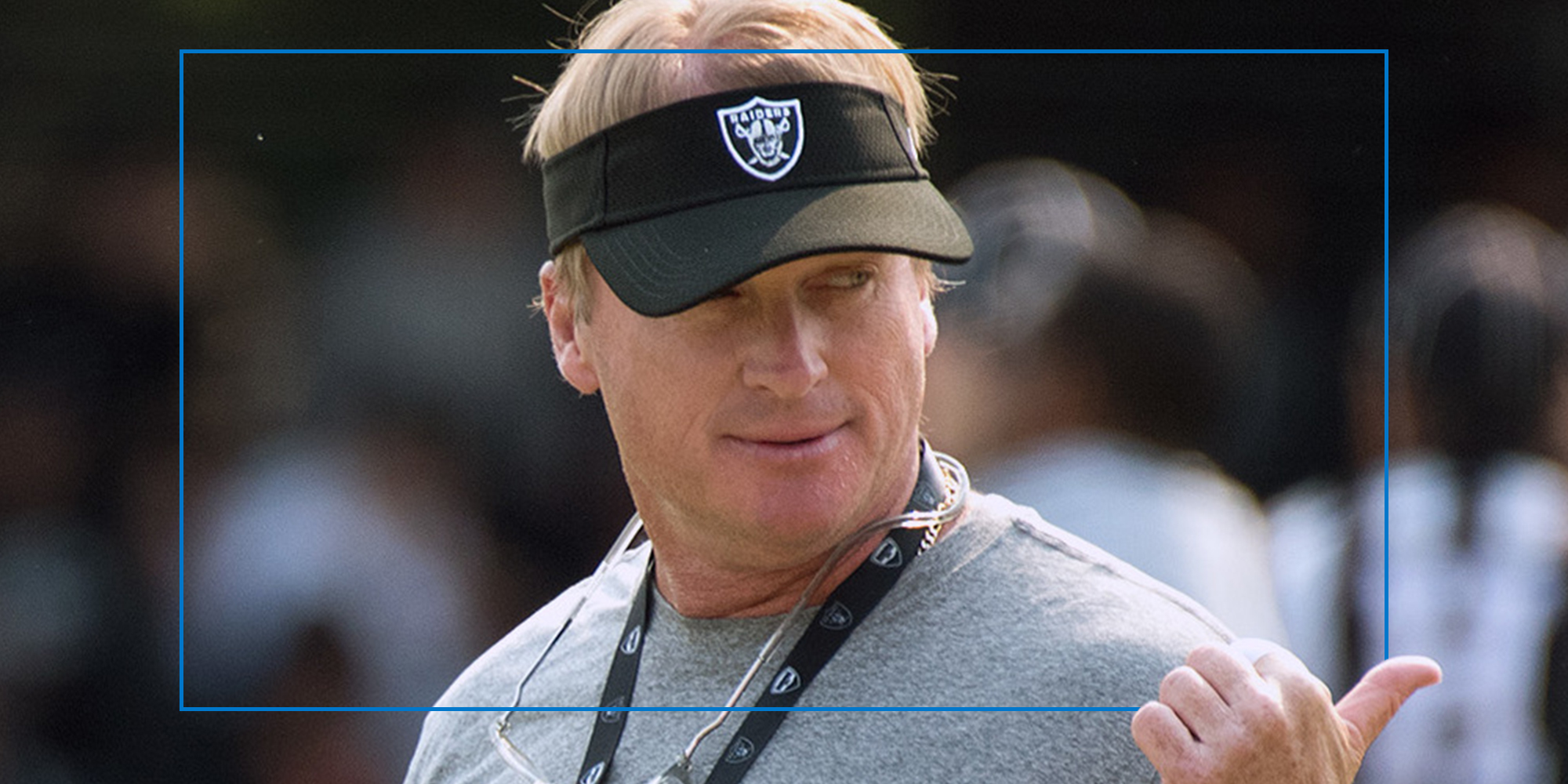

Yet it was evident Iverson was not at all who Stern wanted as the face of the NBA. Even with declining regular season viewership, the commissioner seemed determined to not anoint Iverson with the mega-push to stardom enjoyed by Jordan.

“I honestly thought the NBA didn’t like him and that’s why they issued the NBA dress code. He was not fitting into the uniform standard of what an ‘NBA player should be’ and that scared a lot of people whose main job is to protect the image of the NBA,” Watkins says.

It would be borderline impossible to talk about the way Allen Iverson was viewed by the higher-ups at the NBA without being frank. Stern—and by extension, the league—apparently viewed him as a representation of Black culture and that rubbed them the wrong way.

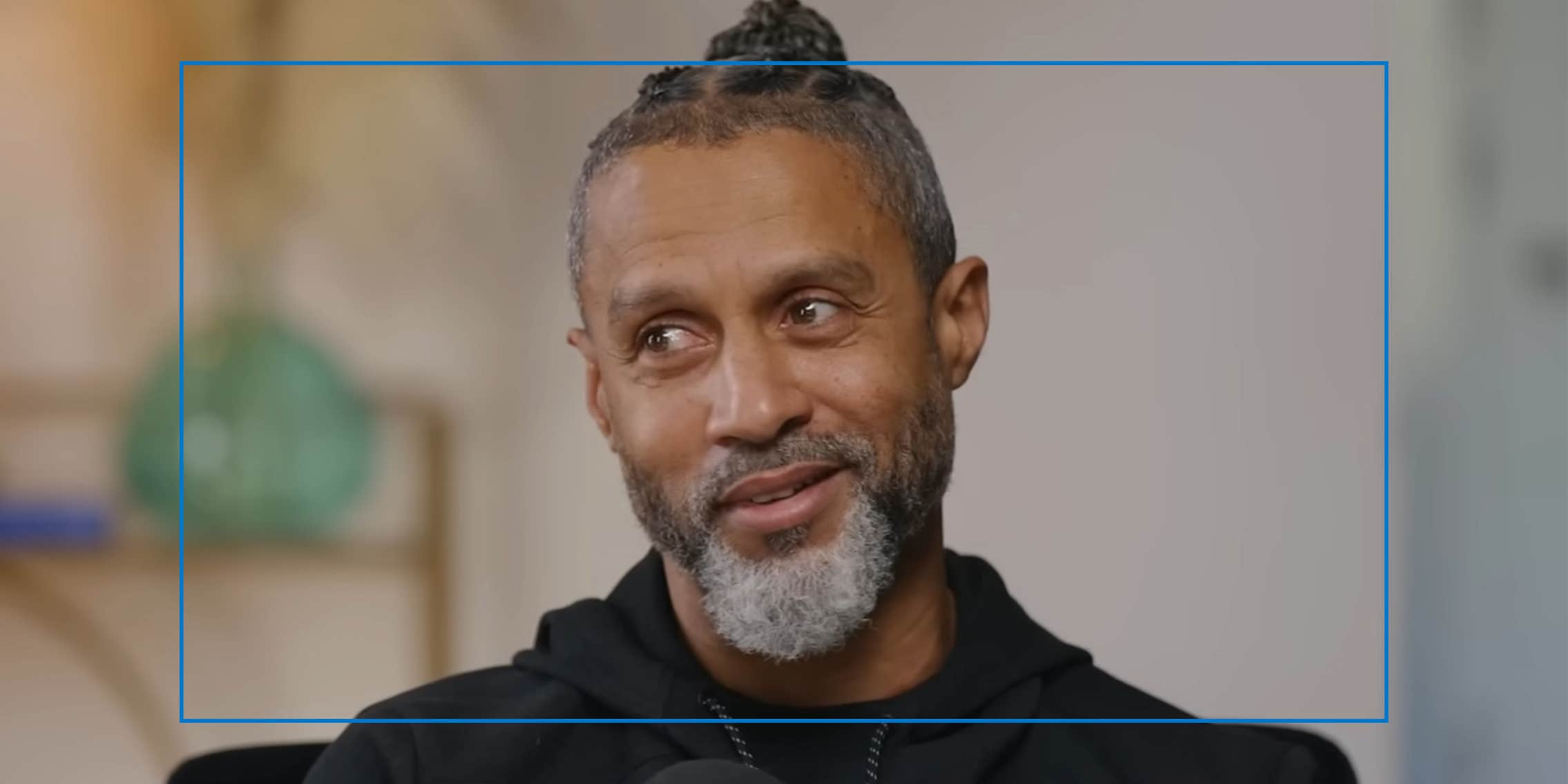

But it was too late for naysayers. Black culture and hip-hop in particular was seeping into every facet of entertainment, including fashion. Early 2000s fashion is seen now as synonymous with the music of the time and this affected the way NBA players dressed on and off the court, and standing at the front of this revolution was Iverson. A look complete with braids, baggy shorts, and tattoos seemed to be the type of image that would wake Stern up at night in the coldest of sweats. Even without the league’s direct support, the momentum train for the man known as “A.I.” was hard to slow down, and one company in particular seemed to be betting on that.

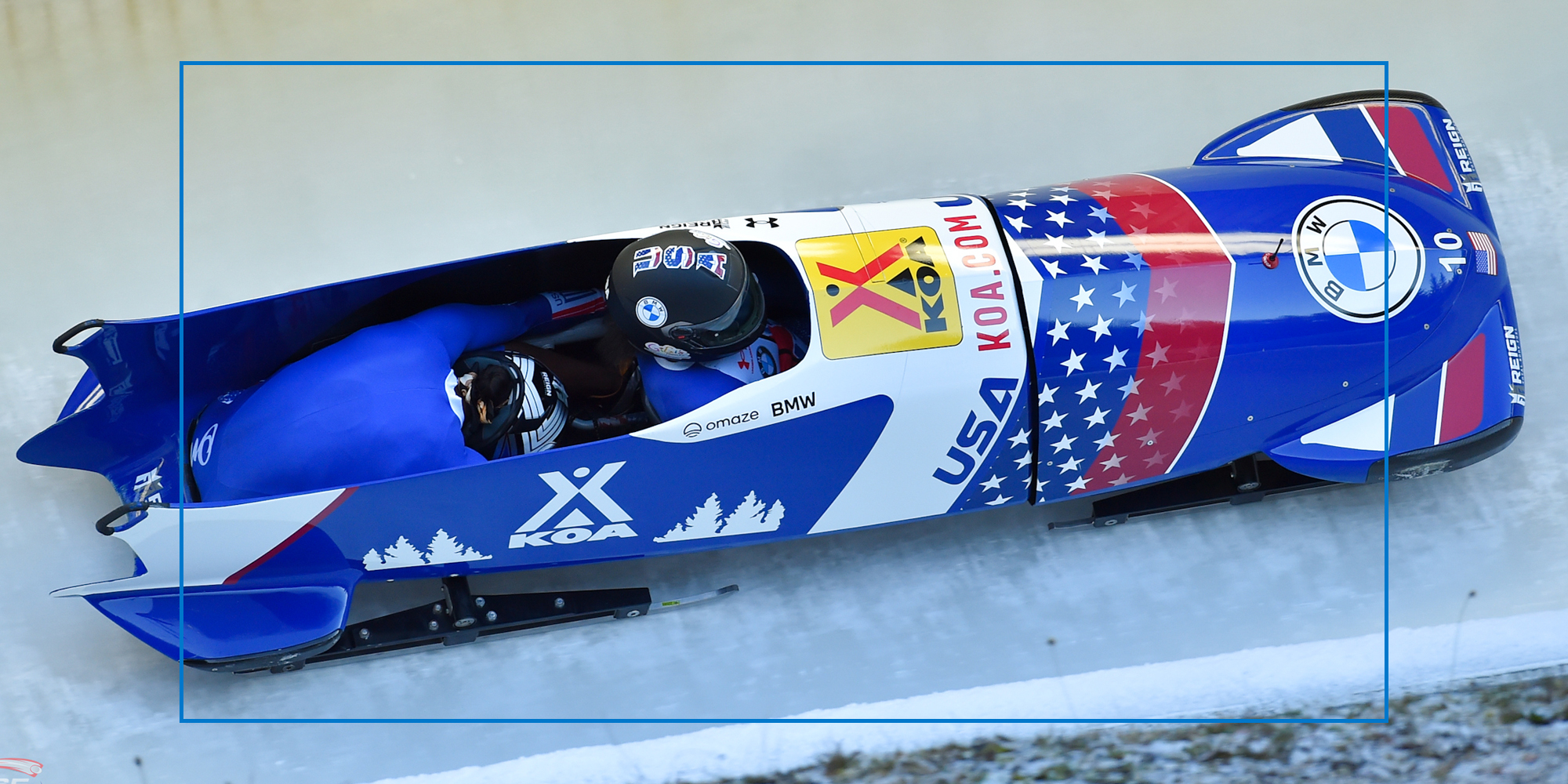

After fledgling sneaker company Nike managed to sign the greatest athlete of the generation in Michael Jordan, Reebok spent the next 15 years playing catch-up. It eagerly teamed up with a young lighting rod straight from Virgina. In 1996 (Iversion’s rookie year), Reebok unveiled his first signature shoe “The Question”—a play on his nickname, “The Answer”—with each subsequent shoe release taking on his nickname.

By 2001, the series was preparing for its fifth installment, the aforementioned ”A5.” Before, each campaign sought to capture some part of Iverson and alluded to his “bad boy” image without truly diving into what made Iverson so unique—his Blackness. This wasn’t due to concerns about profiting off of culture; Reebok mainly just seemed unsure about the staying power of hip-hop and if it would translate to a largely white customer base.

Reebok took the risk and delivered the groundbreaking commercial and campaign for the Answer 5. The ad featured Jadakiss, the former Bad Boy Records star and breakout voice of group the Lox, rapping along to a Trackmasters beat made up of Iverson’s dribbling thuds, his squeaking-on-the-hardwood sneakers, and swish splashes. He was showing off every dribble combination he’d learned since before his time at Georgetown. For his part, Jadakiss’ rhymes are sleek, focused, slyly funny, and subtle. Each simile is tightly written and perfect: “The way he breaks down the defense, it’s like he got the ball on a string.” And when it’s time for the hard-sell, Jada closes: “I keep an extra pair in my car, in case you want to take it to the park.”

In just under a minute, the commercial cemented itself in history. As major corporations were jockeying for position in the entertainment landscape, out escaped a reflection of the youth of that day nearly uninterrupted by majority opinion.

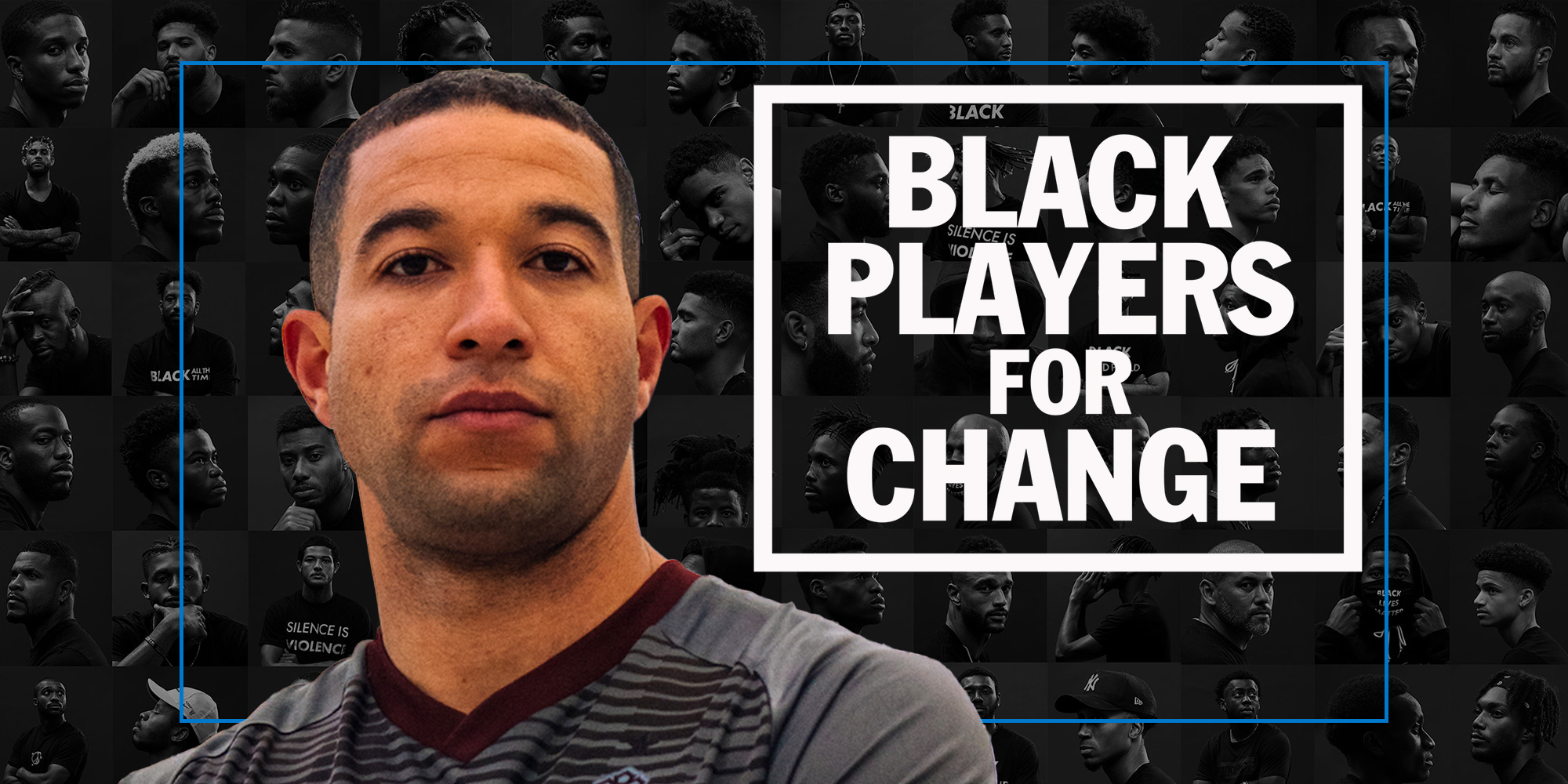

What many failed to see before the campaign is that entertainment was not in a phase, it was truly changing and different groups who previously had no way to find others like themselves now had a place of refuge.

Where this convergence of cultures took place was largely the internet. In 2001, the Dot Com bubble was beginning to burst and to many it seemed that the lofty expectations placed on the idea of a “world wide web” would go unfulfilled. However, in many forums and chat rooms during the early stages of the internet, like-minded people were finding each other and interests were beginning to blend.

According to Vice, most Americans did not have the internet during that time. But looking at Pew Research from that same time period, around 72% of adults ages 18-29 did use the internet somewhat regularly, showing a larger generational shift that was also reflected in both music and fashion.

The web became the perfect backdrop to a societal shift and an entirely new era of marketability. With Blackness, culture is simultaneously created and sold—making who we are feel both unique and obtainable for any who would wish to cosplay at the right price. Black-led hip-hop culture was and is elusive to capture in its purest, messiest form. It’s been the key to its survival.

In the modern digital era, where more people and cultures than ever have a platform, the desire of corporations to cash in on whatever and whomever they can align themselves with has increased. But in 2001, the circumstances that led to the creation of Iverson’s A5 campaign required a perfect storm.

See more stories from Presser – examining the intersection of race and sports online.