Analysis

Ahead of the May 17 lottery, prognosticators are busy preparing rundowns of young NBA prospects. These players, scattered across the globe, will be forced into a depot of the NBA’s worst-run franchises—at least on average. An occasional playoff team beset by injuries sometimes leads to a lottery fortune.

You, the player, are owned by the team, as dispersed via a weighted lottery system. Even the language confers ownership: The league’s commissioner says a pick “belongs” to a particular team. Regardless of the player’s desire, these franchises will select from the very best young talent globally, hoping that said talent could overcome the organization’s inability to field a competitive team otherwise.

These poorly-run franchises will publicly pin hopes of a turnaround to the player, who is assuredly tied to the front office’s ability to develop him and pursue surrounding talent fitting his skill set (or match his skills within the framework, if he’s not a “franchise” player).

However, many will say, “Bad Team X will pay Player X millions!” Yes, he could, if picked in the first round; however, his salary will also be tethered to an arbitrary scale pinned to his draft spot—a scale primarily created to prevent predominantly Black and American draftees from receiving relative market value. And then, there’s a faulty presumption of parity.

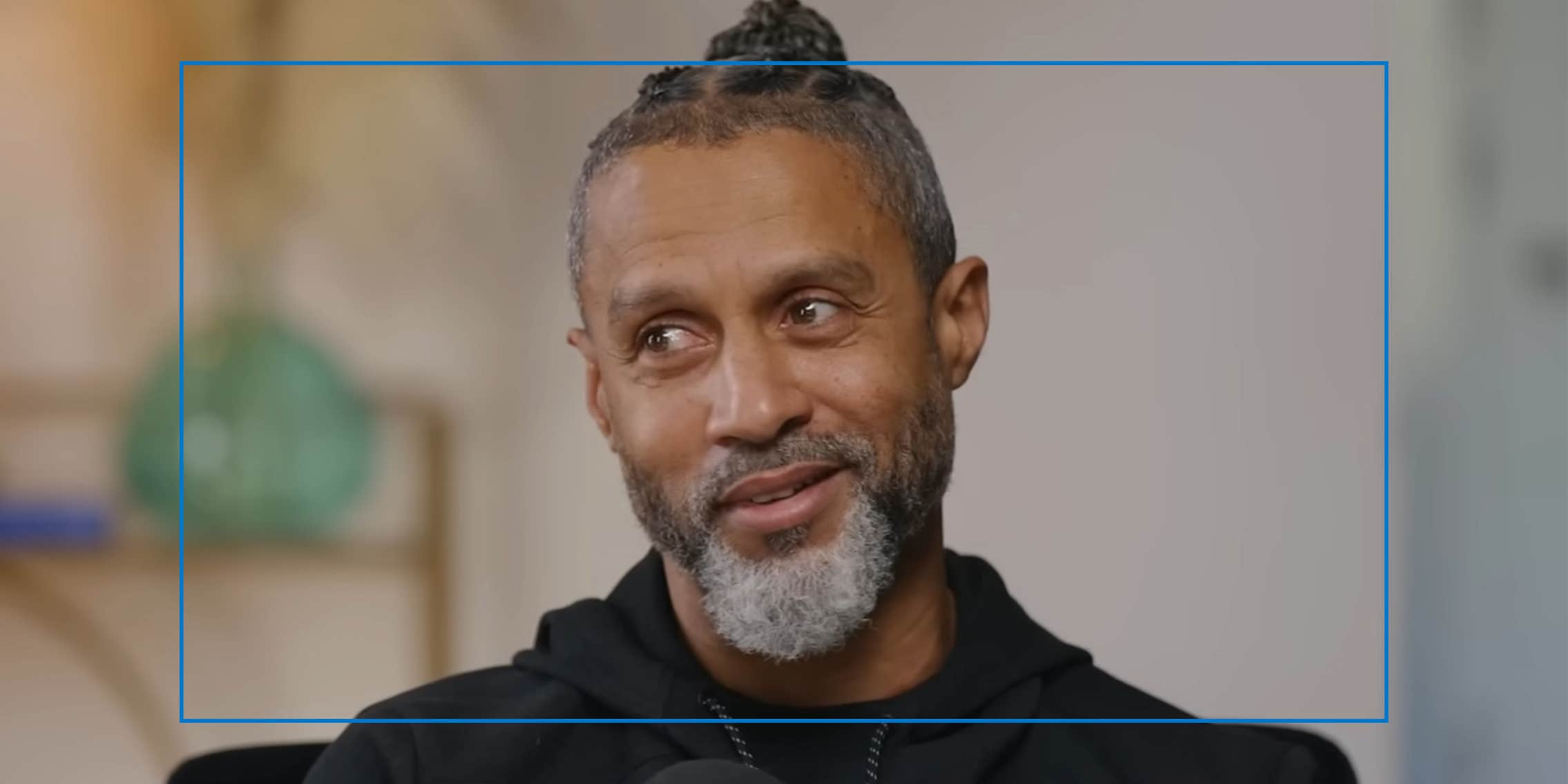

“I’m generally skeptical of the American pro sports competition model. Essentially, all the professional leagues, especially the NBA, don’t make decisions based on increasing competition,” said Phillip Lamarr Cunningham, assistant professor of media studies at Wake Forest, in a phone call. “They make [decisions] on basically assuring a false level of parity. The false sense that a team not in a significant market gets first dibs at players who could be transformative.”

The preceding setup is one that is not even remotely allowable in any other line of work in the United States. A prospective contractor coming out of college, high school, internationally, or from a post-graduate G-League season has no way to determine his immediate future. There’s no proof that the draft elevates poor teams out of basketball squalor. This and several additional factors—including loaded language around contracted mostly Black athletes—details why the NBA should abolish its draft.

How it started

From 1947 through 1965, teams made picks out of “territories” based on each franchise’s location. In 1966, the league adopted a coin flip between the last-place finishers of two divisions—the NBA had just ten teams at the start of the 1966-1967 season—to determine which team drafted first. The remaining clubs were picked by reverse win-loss record (worst to first/NBA champion). According to NBA.com, in 1984, the NBA Board of Governors voted to begin using a weighted lottery system after the Houston Rockets—who already picked the 7’4″ Virginia star Ralph Sampson as No. 1 overall pick in 1983—lost 14 of their last 17 games, tanking themselves into the coin flip. They won and drafted Hakeem Olajuwon in a draft that included Michael Jordan, Charles Barkley, and John Stockton. (The Chicago Bulls did the same to position themselves for either Jordan or oft-injured Kentucky center Sam Bowie, losing 14 of their final games.)

The lottery was also supposed to help smaller-market franchises—the supposed runts of the NBA litter in the eyes of top free agents. Historically, however, large-market teams often gamed the system. Famously, the 1985 draft lottery bears controversy as the New York Knicks would have their envelope pulled from the hopper by pioneering commissioner David Stern, leading to the selection of Georgetown center Patrick Ewing. In 2018, the league—combating tanking for high picks—installed a new system balancing the odds for each of the three teams—with the worst regular-season records—at the top of the NBA Draft Lottery to win a 14 percent chance of receiving the first overall pick.

The draft usually ends up a polished collective poking-and-prodding of mostly Black players. Reducing the person to physical ability concerning basketball (or NFL football) becomes inherent. It’s assumed to be a one-way affair—the interviews, the workouts, the public discourse. The teams scrutinize you: you, a well-paid chattel, cannot investigate the gatekeepers.

“When you’re dealing with two overwhelmingly Black leagues, the draft takes on a completely different connotation,” said author and historian Dart Adams. “It represents something different when it’s a bunch of Black bodies being tested, interviewed, inspected, and prodded.”

The lows of high school

High school players, resting at the core at an argument against a draft, were once eligible to be drafted, emanating from a critical Supreme Court case. Haywood v. National Basketball Association was a decision that ruled against the NBA’s requirement that an NBA team could not draft a player until four years after graduating from high school. In an in-chambers opinion, Justice William Douglas allowed Spencer Haywood to play in the NBA in a temporary stay. Haywood’s case against the league settled out of court, and the latter adjusted its four-year rule to allow early entrants in cases of financial hardship. Kevin Garnett, drafted fifth in 1995 to the Minnesota Timberwolves, served as the test case as the first prep-to-pro player in 20 years. However, the NBA would again ban high school players from entering the draft after the 2005 draft.

Hardened divisions exist along the prep-to-pro faultline, either for or against entry without a post-graduate year. Some players—such as Korleone Young, Lenny Cook, and Ousmane Cisse—presumably should have qualified for collegiate eligibility. From their respective draft nights onward, numerous talking heads have pumped the notions of forcing talent through the college ranks, suggesting both the NCAA and NBA would benefit from disallowing high school players. This idea is a massive farce that provides cover for teams unable or unwilling to scout or develop players adequately.

Further, the raw numbers suggest high schoolers have strong odds in becoming, at minimum, quality starters and valuable contributors in the NBA. 30 prep stars were drafted in the first round during the lottery era, including nine players earning All-Star selections, eight players with All-NBA selections, and nine becoming NBA champions. Kwame Brown, Dwight Howard, and LeBron James each went No. 1 overall in their drafts. The group also includes three Hall of Famers (Kobe Bryant, Kevin Garnett, and Tracy McGrady), with two others (Howard and James) marked for induction.

That high schoolers not allowed into the league has nothing to do with readiness for competition and everything to do with the contracts the league must satisfy for talented 18-year-olds who will have longer careers than college players—especially players who might play until they’re at least 37 and still be good enough to lead the NBA in scoring.

A great depression

One of the primary arguments for abolishing the NBA Draft is that it is essentially an apparatus for corporate welfare. It creates and feeds a bubble of elitist-socialist behavior that perpetuates class and labor warfare. Here’s where language continues to be important: The NBA is a league of individual, independently-run franchises, not a single business with various teams as divisions. And players aren’t “employees”; they are independent contractors.

“I think as you’ve seen how much more oppressive management in leagues have been toward players and unions and keeping costs down, it becomes clearer that it’s not just about control of the individual athlete,” said writer and founding Deadspin editor Will Leitch, over the phone. “It’s really about control of finances and being able to keep costs unnaturally down.”

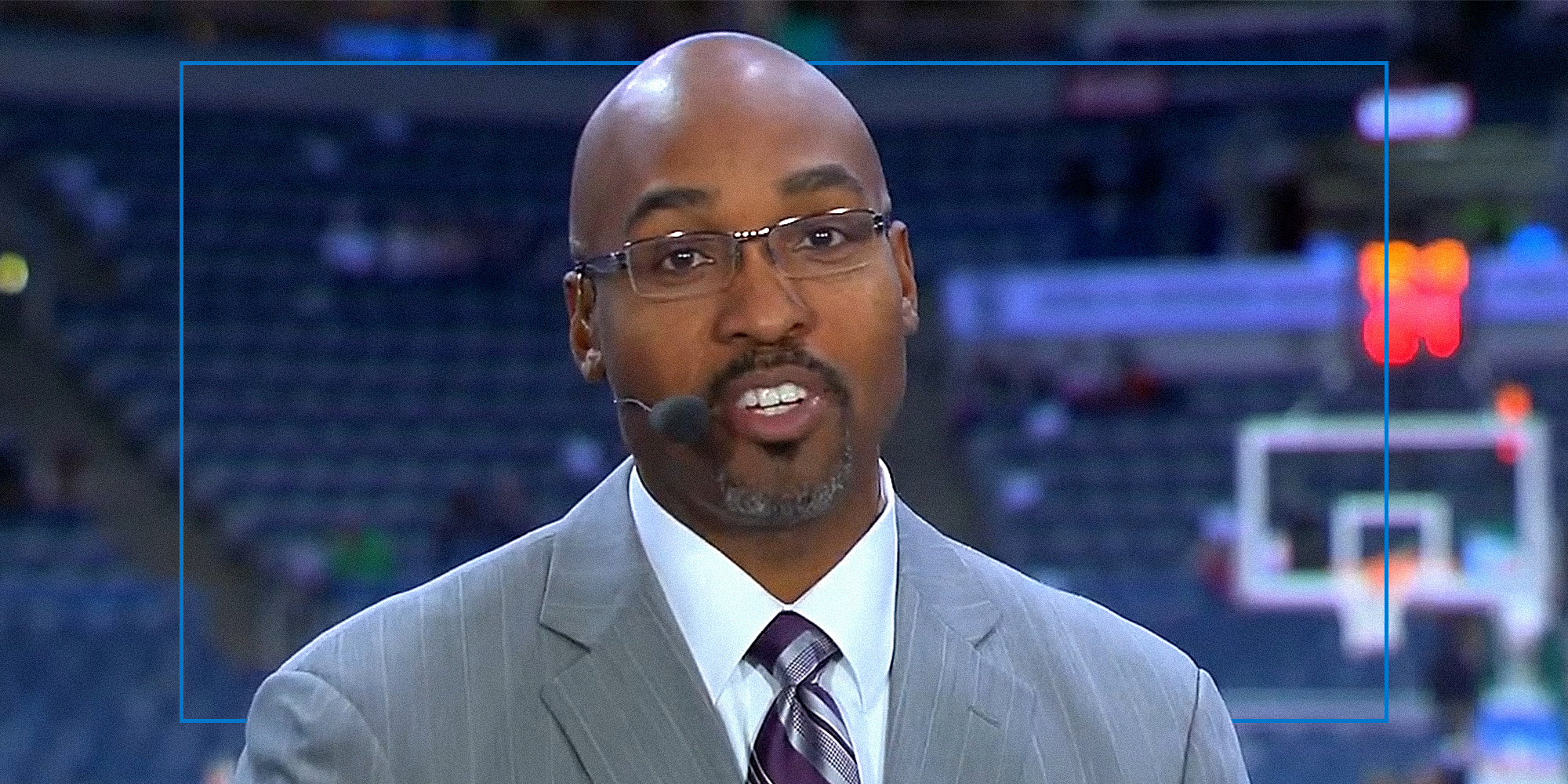

After the 1994 draft, No. 1 overall pick Glenn “Big Dog” Robinson signed a 10-year, $68 million contract with the Milwaukee Bucks before ever playing a game—rankling wealthy franchisees and bootlicking veterans all-too-ready to depress their own wages to limit rookies’ influence on the game. As former ESPN NBA expert Amin Elhassan noted, the NBA created the rookie scale, making high lottery picks even more valuable for a few reasons, especially after 1999, which tacked on a fourth year—which meant players couldn’t receive extensions until after a third season.

Added Elhassan: “The final CBA stroke was implementing the luxury tax in 2005, penalizing teams for spending above the tax threshold, making this ‘cheap skilled labor’ even more valuable. The combination of (A) having draftees beholden to negotiating with only one team, (B) underpaying them for their troubles, (C) keeping them underpaid for a longer period and (D) avoiding financial penalties made first-round picks infinitely more valuable.”

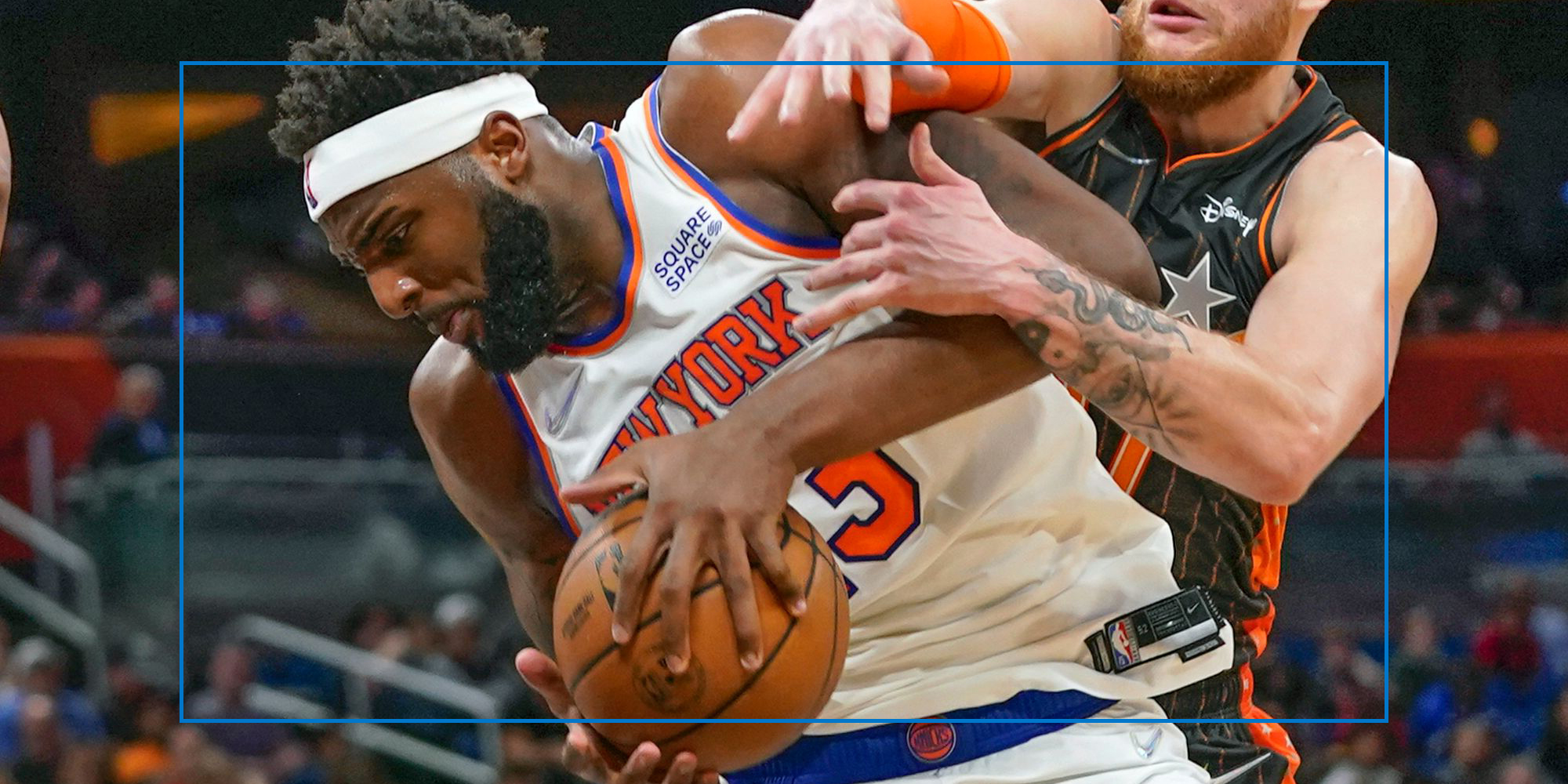

The move made tanking even more prevalent, most notably during the so-called “Process” for the Philadelphia 76ers. In consecutive drafts, the franchise captured top-3 picks (Joel Embiid, Jahlil Okafor, Ben Simmons, and Markelle Fultz). Only Embiid remains a Sixer as of 2022. Okafor is playing basketball in China.

The Philadelphia experiment shouldn’t have occurred based on the NBA’s rationale. Philadelphia is neither a small-market team nor have they found great success from the tanking model. Why? Because tanking essentially doesn’t work unless you procure Tim Duncan, LeBron James, or Shaquille O’Neal—all-time, all-universe talents making up a tiny portion of all the NBA-level talent that’s ever existed.

“There’s logic is based on parity, the idea that if the league didn’t give certain teams access to these players, then they would be in trouble because no free agents would want to go to these small-market teams—we’re thinking the Utahs, the Minnesotas, the Oklahomas of the world,” explains Cunningham. “Conversely, if that’s true, why are you in those markets in the first place? That’s a whole different discussion altogether.”

For example, Oklahoma City Thunder drafted Kevin Durant, Russell Westbrook, and James Harden in consecutive seasons. Despite a load of talent at below-market value—and including a young shot-blocker in Serge Ibaka—none of them remain, with just a single trip to the NBA Finals trip to count for general manager Sam Presti’s efforts and drafting excellence.

Both the Philadelphia and Oklahoma City situations detail a specific reality: There’s no indication that the draft improves teams in the fashion intended. The goal isn’t simply to build a team to win for a short period; it is to forge an extended relationship with a player. But what if the player doesn’t want to play for the team that drafted them? This notion would not be an option for most players, as they’ve never seen a professional check they could reasonably turn down—it’s simply too risky as a player coming from nothing. However, it was an option for one player, a player too entrenched into various systems to buck them.

The curious case of Danny Ferry

It was technically two players. After two strong seasons at Oregon State, Jose “Piculín” Ortiz—already a star in native Puerto Rico—was selected by the Utah Jazz in the first round in 1987. While Ortiz did not pan out in the NBA, he went on to a storied international career. In hindsight, it’s a curious selection, given Utah already had a productive young power forward named Karl Malone on its roster. The 15th overall pick immediately elected to play in Spain, though his reasoning centered around 1988 Olympics eligibility. Before a 1989 vote, FIBA (and the NCAA) held an unusual rule where you remained eligible as an “amateur”—even as a professional anywhere else globally—until you played in the NBA.

Duke forward Danny Ferry—the son of former NBA player and then-Washington Bullets executive Bob Ferry—was drafted second overall in the 1989 draft by the Donald Sterling-owned Los Angeles Clippers, one of the worst-run teams in the NBA. (Yes, that Donald Sterling.) The player was worried L.A. would draft him and had interesting ideas around the idea of being forced onto a team. Mick Minas wrote in his 2016 book, The Curse: The Colorful & Chaotic History of the L.A. Clippers, that “Ferry made his feelings about his predicament known, saying it was unfair that players were given no say in where they would start their professional careers and labeling the NBA draft system as un-American.” He was uniquely framed in the press as a “political science major” who was “envious of his schoolmates who studied abroad.” He wasn’t ‘ungrateful‘ or ‘difficult.’ The press did not assign the chattel language to Ferry that it often uses to discuss Black players.

“It’s interesting but wholly unsurprising to see how players like Ferry are seen as making intelligent decisions in bucking the system,” said Cunningham in a second conversation. “There’s something to say that players like Ferry are also insiders. Like the Mannings—NFL quarterback royalty starting with Archie and his sons Peyton and Eli—Ferry was a legacy kid.”

Ferry didn’t shake any trees within the league; his father is an executive. Admittedly confused on why the Clippers would draft him with Danny Manning, Charles Smith and other forwards on the roster, the Naismith Award winner reluctantly accepted a $4 million-a-year package contract to play for Il Messaggero Roma (now Virtus Roma) in Italy’s top basketball league. Instead of playing through competition, he took an agreement that included a lush apartment, a personal chef and maid, a $75,000 BMW, $12,000 Concorde flights for Ferry’s family, and an opportunity to continue his post-graduate education, tuition-paid. These were throw-ins that David Falk, Ferry’s agent, asked for to buy time with the Clippers. He and Bob Ferry sought to use the deal to push Sterling into trading the All-American to the San Antonio Spurs (alongside the incoming David Robinson), the Bullets, or another team. And for all of this, he wasn’t called “soft” for ‘running away from the grind,’ or being difficult—just a young man with a unique opportunity.

In his autobiography, “Le mie Bombe,” coach Valerio Bianchini says that he was asked by the owner—”great playboy” and agro-tycoon Raul Gardini—to take on Ferry to make noise in America. Il Messaggero also signed Brian Shaw, a then-disgruntled Boston Celtics guard looking to restart his NBA career in just his second season as a pro. The Italian job did not go very well for Ferry.

Per an Associated Press report, after 30 regular season games—Italy played most games once a week, on Sunday—the 6’10” forward averaged 22 points and just six rebounds a game. To this day, all top-flight European leagues are more physical than the NBA. In contrast, Shaw, a 6’6″ point guard, averaged 25 points and nine rebounds a game—both team highs. In the season’s final game—a 111-103 loss to Scavolini Pesaro—Shaw scored 46 points to Ferry’s 16.

Sterling eventually traded Ferry to the Cleveland Cavaliers, who apparently had not scouted Ferry during his Italy season. But they, too, were in interesting straits with star guard Ron Harper, allegedly associating with drug traffickers, so they dealt him for Ferry and young forward Reggie Williams. Cleveland recklessly strung Ferry up with the golden noose, a then-blockbuster 10-year, $34 million (with incentives) contract he wouldn’t approach warranting until its last few years—punished by a perceived promise he had not bestowed upon himself.

It was rumored that Cavaliers head coach Lenny Wilkens had lunch with Bianchini during the 1990 offseason after Ferry signed the contract. The latter allegedly informed Wilkens that Ferry would not live up to the agreement and that he was barely passable as an NBA role player. The reality was—as exhibited in the YouTube video of a March 1990 loss to Viola Reggio Calabria—Ferry was in trouble from the start. First, after the draft, even his father had recognized that his son would not carry a team, something you might expect from a No. 2 overall pick. As a former player and talent evaluator, the elder Ferry knew his son wasn’t a stone-cold killer.

David Falk would claim the long Italian practices hurt his client’s knees. Perhaps a true statement. Ferry’s contract likely set up the track toward the rookie scale, eliminating market value for incoming talent. Even more accurate was that Ferry was a classic tweener and a defensive liability who wasn’t quite ready for the NBA’s rigors. He wasn’t quick enough to cover small forwards or strong enough to guard (or score efficiently over) traditional NBA-level power forwards.

Going to Italy, in hindsight, was the best thing that happened to Ferry’s career. Between the glut of gifted forwards and Donald Sterling’s foolishness, his Clippers experience likely would have buried him in a shallow grave. As it were, he went on to a fine career as a role player and won a championship with the Spurs in 2003. He later became a general manager like his father, though his tenure as general manager of the Atlanta Hawks came to a highly problematic end.

The entire tale is informative in multiple directions. Sterling drafting Ferry was a shit-to-sugar stroke of luck because it landed Ron Harper, a fantastic wing, on his way to superstardom before an ACL tear in 1990. (Additionally, the eventual five-time NBA champion had never been found liable for any wrongdoing—drug-related or otherwise—stemming from Cleveland.) Being out of sight and out of mind in Rome allowed Cleveland to foolishly overpay Ferry on potential because they had not done their due diligence and sent a trained NBA scout over to watch 2-3 games of Ferry against more physical, albeit lesser, competition. In a disastrous press release following the trade, they also carelessly positioned him in analog with David Robinson (who served two years in the U.S. Navy before his NBA arrival in 1989) concerning the wait for the player and Larry Bird as the next great white superstar.

Both the Clippers and the Cavaliers failed Danny Ferry long before whatever failures attributed to him.

The fix

When a player is drafted by a franchise, what should be understood is that the league, on the whole, is first absorbing them as unorganized individuals. The team’s selection is secondary. In this specific and vitally important stage, entry into the player’s union is tertiary. Ferry, a privileged white man, ultimately retained options unavailable to most draft entrants, especially Black players. Given his talent, class advantage, and NBA connections, the fact that it still didn’t work out details why it would be problematic for a player of lesser privilege to challenge the draft system’s certainty. (This is relative, as he was an NBA player for 13 seasons.) Ferry could not have signed with the Clippers and re-entered the draft, which was untenable for most players, as most lacked means. A player should not be punished for taking themselves out of a process in which he holds no power and retains no real self-agency.

There are plenty of ideas for fixes to the draft, including its complete elimination. But the immediate solution should start with language. Soft class and labor warfare vocabulary and actions around the responsibility of success and failure must change. With Black players making the bulk of the talent, there’s often a racialized aspect in the pushing and pulling of Black bodies in directions not mutually agreed-upon, usually covered in production value sheen of draft day dramatics. The team/league should also be asked: Is the player a trinket for ticket sales, or is the franchise attempting to win? Do their actions indicate they plan to use the player to the team’s benefit without harming the draftee?

Danny Ferry isn’t a bust; he and his father knew the Sterling-led Clippers were an unwinnable trap. He had every right to work whatever angles were available. Nor is 2013 first overall pick Anthony Bennett; he didn’t pick himself in a mostly-subpar draft where even ESPN college basketball expert Jay Bilas had the one-and-done UNLV star as his sixth-ranked player. Nor Sam Bowie, the injury-prone center, picked ahead of Michael Jordan in 1984.

There is no such thing as a bust. Player success or failure is first the responsibility of the team, then the player—and only if the latter fails even if afforded mutually agreed-upon conditions. It is the players who have essentially submitted themselves to a crapshoot of wayward, sometimes-visionless franchises—not the other way around.

See more stories from Presser – examining the intersection of race and sports online.