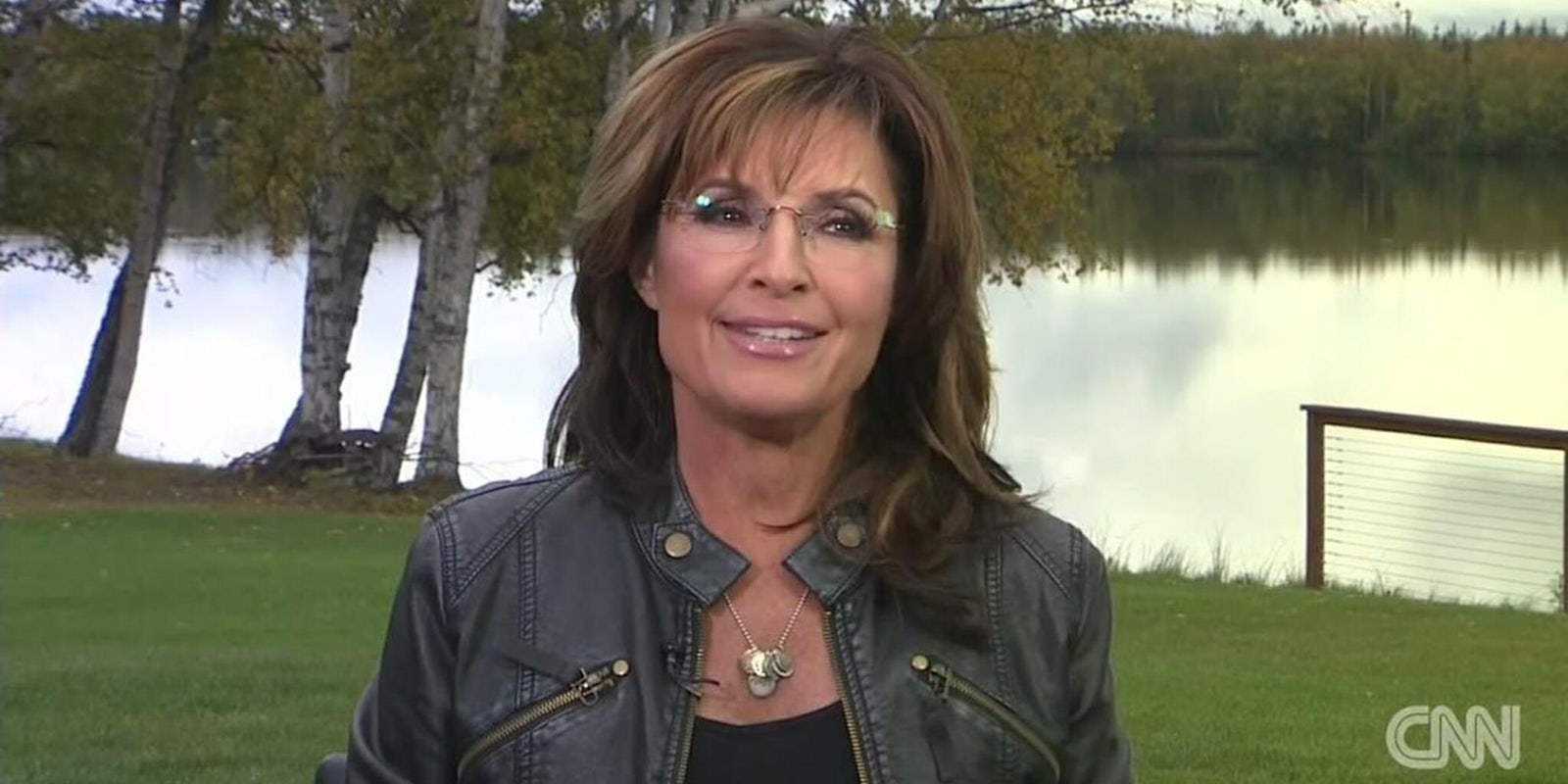

If you’re in America, you speak American, so says former Alaska governor and 2008 vice presidential candidate Sarah Palin. Palin appeared on CNN Sunday and commented on GOP frontrunner Donald Trump’s criticism of Jeb Bush for answering a question in Spanish during a visit to McAllen, Texas. Trump told Breitbart that Bush is “a nice man, but he should really set the example by speaking English in the United States.” And Palin certainly agrees.

“It’s a benefit of Jeb Bush to be able to be so fluent, because we have a large and wonderful Hispanic population that’s helping to build America, and that’s a great connection he has with them,” Palin said to CNN’s Jake Tapper. She added, “When you’re here, let’s speak American… I mean that’s just, that’s… let’s speak English … and that’s kind of a unifying aspect of a nation is, uh, the language that is understood by all.”

But in a country with almost 400 spoken languages, according to the 2011 Census, what does “speaking American” actually look like? For Palin, it looks a lot like herself, who speaks with a small-town twang, but it’s also deeply indicative of the conservative ideal of what America is in 2015—and who fits in it.

Although Palin took Spanish and French in high school, her feelings about speaking “American” run parallel to the swelling of xenophobia in America during the campaign season, as well the imaginary crisis of a cultural takeover by immigrants from Mexico and Latin America. But a key component of the Sarah Palin character is how she speaks for the everyday American (read: white, working class). She peppers her speech with colloquialisms like “flyin’ flip” to maintain that small-town image, which she considers the “real America.”

Twitter was quick to respond to Palin’s apparent elementary-level speaking ability, as well as the fact that there is no single American language.

Sarah Palin wants immigrants to speak “American.” Sarah Palin should be deported.

— Hari Kondabolu (@harikondabolu) September 6, 2015

‘Immigrants should speak American’ demands Sarah Palin.

— Piers Morgan (@piersmorgan) September 6, 2015

There is of of course no such language.

Before mocking Sarah Palin out for being dumb, keep in mind that she’s fluent in American, Canadian & Australian.

— Kevin O’Neill (@KevinBuffalo) September 6, 2015

As in any culture, there are countless variations of language and dialect. American dialects are influence by region, by immigrant population, and by the ethnic origin of its settlers. For instance, Pennsylvanian English is heavily influenced by German, Mexican dialects melded with English in the Southwest, and in Louisiana, French, English, and Creole languages meshed together. In fact, Palin’s signature Wasilla, Alaskan accent combines Russian and Native American speech with Midwestern and Canadian dialects.

Interestingly enough, Sarah Palin’s own accent is the ultimate indication that English in the United States is so variant that it’s impossible to nail down what the American language would begin to look like. While English certainly dominates the American lexicon, it simply represents the language of the dominant colonial ancestry that began in the 17th century. It’s not just that language itself has changed since then, due to various cultural influences, but that America itself continues to evolve through immigration.

Opponents of a multilingual America fear that English will eventually disappear or become a minority language—due in part to the significant number of Spanish speakers in the country. According to the Instituto Cervantes in New York, the U.S. has 41 million native Spanish speakers and 12 million bilinguals. This means America is second only to Mexico for most Spanish-speaking country. The report projects that, by 2050, 132.8 million people will speak Spanish in the U.S.

However, Spanish is unlikely to become the predominant language, even with those numbers. Children of immigrants, and of Spanish-speaking families, increasingly consume English media at higher rates, and the number of Latino youth with proficiency in English is on the rise.

Despite the fact that Latinos and other immigrants are assimilating to American English, the sheer cultural force those populations exert (41 million!) scares figures like Palin and Trump, and it’s consistent with American patterns of nativism that date back to the founding of the nation. Benjamin Franklin once decried the influx of Germans to America in the 1750’s.

Few of their children in the country learn English. … The signs in our streets have inscriptions in both languages. … Unless the stream of their importation could be turned they will soon so outnumber us that all the advantages we have will not be able to preserve our language, and even our government will become precarious.

He added, they are the “most stupid of their nation.”

Of course, if we are to take Palin literally, it could be argued that “speaking American” actually means learning one of the many languages of the Native population. The 2010 Census counted 169 Native languages still spoken in the U.S.—by just under a half-million people. Granted, many Native North American languages are extinct, a result of the mass genocide that took place since the first settlers came to the country.

The fact that those immigrants didn’t learn and preserve the languages of those they oppressed is a reminder of what the debate over “speaking American” is really about: exerting power by setting the terms of discourse. It’s easy to take for granted the fact that many Americans speak English without considering the often violent history of that language. When Americans speak, they don’t speak in a cultural vacuum.

But people like Palin and Trump would rather erase the real legacy of America’s melting pot. What these politicians are doing is nothing new—exploiting old fears and hatreds to deny the contributions and the cultural footprint of other populations in America. The approach has largely worked for Trump—who is still leading in GOP polls early in the primaries, in addition to attracting outsize media attention. Although America is changing, many of its worst tendencies are not.

Feliks Garcia is a writer in Brooklyn. He holds an MA in Media Studies from the University of Texas at Austin, is Offsite Editor for The Offing, and previously edited CAP Magazine.

Screengrab via CNN/YouTube