Opinion

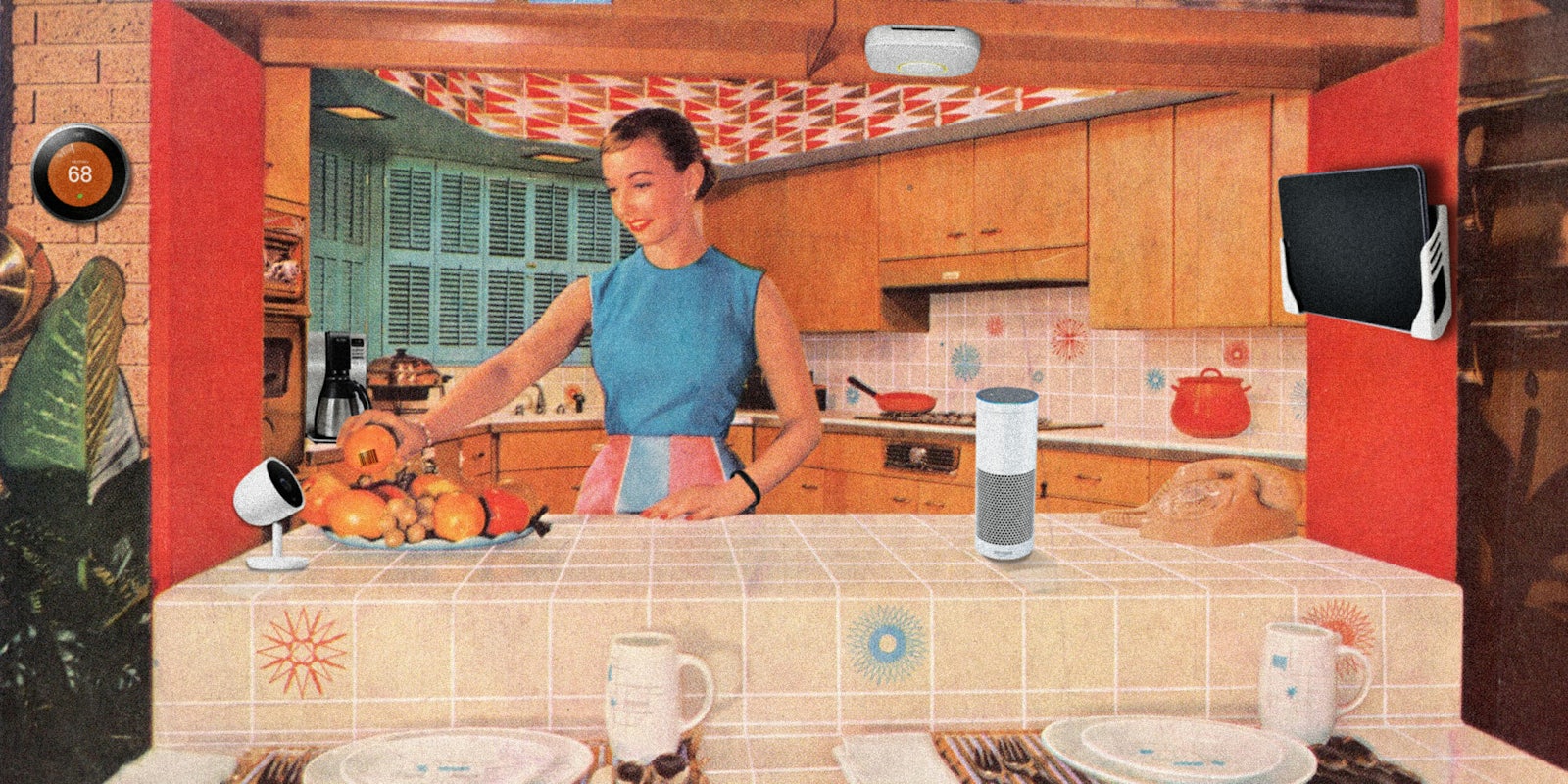

In the past few weeks, the technology press reported that China is forcing its Uighur Muslim minority to install smartphone spyware; iRobot (maker of the popular Roomba robot vacuum cleaner) is planning to share maps of Roomba owners’ homes with its commercial partners; and a casino was hacked through a security flaw in its Internet-of-Things-enabled fish tank. These reports are part of a larger pattern, one that reveals we do not truly own or control our own smart devices.

Looking back over the past several years, we can find many other examples: John Deere claims that farmers don’t really own their tractors but merely license the software that makes the tractor run. Computer manufacturer Lenovo shipped laptops with a deeply flawed spyware program installed that spied on users’ encrypted internet traffic and permitted hackers to impersonate the user. Samsung smart televisions listened in on conversations in the livingroom and bedroom and passed information along to advertisers, or, worse, enterprising intelligence agencies that can exploit the advertising back-channel.

There’s more: The maker of the popular couple’s erotic massage device WeVibe extracted data about how their customers liked to use the device. And one Ohio man was indicted for arson because of data taken from his own pacemaker. Police thought his heart should have been pounding harder during a house fire.

If you think the old-fashioned rules of private property ownership are just about regular land, houses, and cars, you’re wrong. They’re just as much about your control (or lack thereof) over your Nest-enhanced home, smartphone, fitness tracker, or self-driving car.

A major conflict has arisen between the owners of software-enhanced devices and the owners of the intellectual property embedded into those devices. It’s as if when you bought a car, the dealer claimed that she still owned the motor. The question, ultimately, is who will control the so-called Internet of Things: us, the companies that tell our devices to spy on us, or the governments that seek to track and control their citizenry.

Traditionally, when we own property, we are free to use it, repair it, modify it, control it, and most importantly, exclude others from it if they don’t use it as we wish. Those are precisely the rights that the companies don’t want us to have. If we had the right to repair our own digital devices, we might go to a cheaper independent repair shop rather than being forced (as John Deere owners are now) to go to an expensive and often remote repair shop that has negotiated a sweetheart deal with John Deere. If we had the right to exclude others from using our devices when they misbehave, we would be able to ban peeping advertisers from our smartphones, smart TVs, or vibrators. If we truly owned our movies, books, and music, we could sell it to people who need it, the way we sell used textbooks to starving students at a reasonable price.

That is why some internet companies are conducting a quiet war on ownership. A streaming service is an ongoing fee every month. A purchase of a movie, e-book, or MP3 is a one-time payment for something you own from that point forward. Or, at least, it should be: Companies claim in hidden contractual clauses that we do not even own movies, music, or books that we buy outright. They do this to kill off the market for used movies, music, or books. If you’ve ever bought used textbooks for a class, you understand how much killing the secondary market hurts consumers: Everyone has to buy e-books for themselves, at full price.

Another motivation for the war on ownership is advertising dollars. Samsung smart televisions, the WeVibe massager, and your smartphone all spy on you in order to pass information to advertisers about what you are likely to buy. If you search medical terms, perhaps you have a profitable disease. If you search for “divorce,” perhaps you are interested in marital counseling services or a mid-life crisis big-ticket purchase. What’s worse, we reveal much more about ourselves by our search, location, and internet use histories than we know. Big data algorithms can determine our creditworthiness, political affiliation, and sexual orientation from our Facebook profile alone. Adding data from other sensors, embedded in our Internet of Things devices, just makes the predictions even more eerily accurate.

The advertising-focused companies want to lock us out of our own devices because they need to stop us from kicking the spyware out. If we controlled our smartphones (or smart TVs or vibrators) we could ban these peeping companies from our devices. Consider how careful smartphone manufacturers are to design permissions for your apps. Why is it that we must let every ridiculous app scour our contacts list for everyone we know?

The app permissions create the illusion of consent, but there’s nothing consensual about it. Smartphone manufacturers take our normal, everyday right to ban intruders from using our property and require us to permit spying if we want to use our device. Imagine if you hired a workman to put a lock on your front door. Instead, the workman installed a lock you couldn’t open and wouldn’t give you the key until you agreed to let his friends come in and search your house whenever they wanted. It’s like that.

If we want our smart devices to answer to us and not surveillance-addicted companies, we’re going to have to do something about it. Fortunately, there is a little time. The idea of property is deeply embedded in our culture, and we will not easily give up the ability to control what is ours.

There is a reason why the war over ownership has been so quiet. It’s the same reason that the clauses taking away our ownership rights are buried deep in End User License Agreements that nobody reads. Every single one of the above examples was a public relations nightmare for the company involved. Often, merely describing what the company is doing is enough to make it back down. John Deere knows that telling farmers they may not repair their own tractor just looks and sounds terrible. The company wants to keep these stories out of the press and ratchet the heat up on ownership slowly. The goal is to take away our ownership rights slowly and imperceptibly—to “wean” us from ownership and convert us to streaming services, rentals, and paying full price for devices that spy on us without our knowledge.

We can stop this pattern first by noticing it and talking about it. My hope is that consumers will start to notice the war on property, reading between the lines of newspaper articles and the clauses of End User License Agreements to which we all quickly click “I Agree.” This, in turn, might change buying patterns. Consumers might hesitate before buying a Samsung Smart TV, WeVibe, or Lenovo laptop. Smartphone owners might decide to avoid Verizon, with its history of planting tracking tags within its customers’ internet activity.

Instead, people might decide to reward responsible companies, to buy unlocked smartphones, or better yet, phones designed from the ground up to answer to the owner. Farmers might decide to buy from one of John Deere’s competitors. Gamers might choose a console that does not spy on the living room.

Even when an entire industry coordinates against ownership rights (trying to find a smartphone EULA that doesn’t permit someone to surveil your phone is very nearly impossible), owners can still often jailbreak, repair, hack, or otherwise modify their own devices. Companies lobby to make these rights complicated, but we have more power than they say we do. Right now it is legal to jailbreak or root your smartphone or to tinker with your software-enabled car, even while it remains illegal to hack your gaming console or tinker with your tractor. Even though these rules are confusing and constantly changing, it is important for us to know and use the rights we do have, so that we are aware when companies try to stealthily take them.

And finally, although we are a deeply divided nation, the idea of private property still has a lot of influence in our common cultural imagination. Politicians from both major parties support right-to-repair bills in the states. The 2014 federal law that gave us back the right to unlock our cellphones—to hack them to work with any carrier—enjoyed widespread bipartisan support. If we decide that private property ownership is something worth keeping as software is increasingly embedded in our homes, cars, and even in our bodies, we can beat the industry lobbyists and lawyers.

We can be owners again.