In next summer’s Jurassic World—the fourth installment in the Jurassic Park franchise—the trailer opens up with the premise that twenty years after the events of the first movie, nobody learned a single thing since dinosaurs broke free from Dr. John Hammond’s proposed theme park and wreaked havoc on Jeff Goldblum (and others). That was just an isolated part of the island, though.

In Jurassic World, for some inexplicable reason, entrepreneurs have funded an entire island full of dinosaurs, taking the theme park concept Hammond conceived in the first movie and extrapolating it in a huge way. Who wants to bet the entrepreneurs who are now funding the island are the twisted businessmen from Hostel 2?

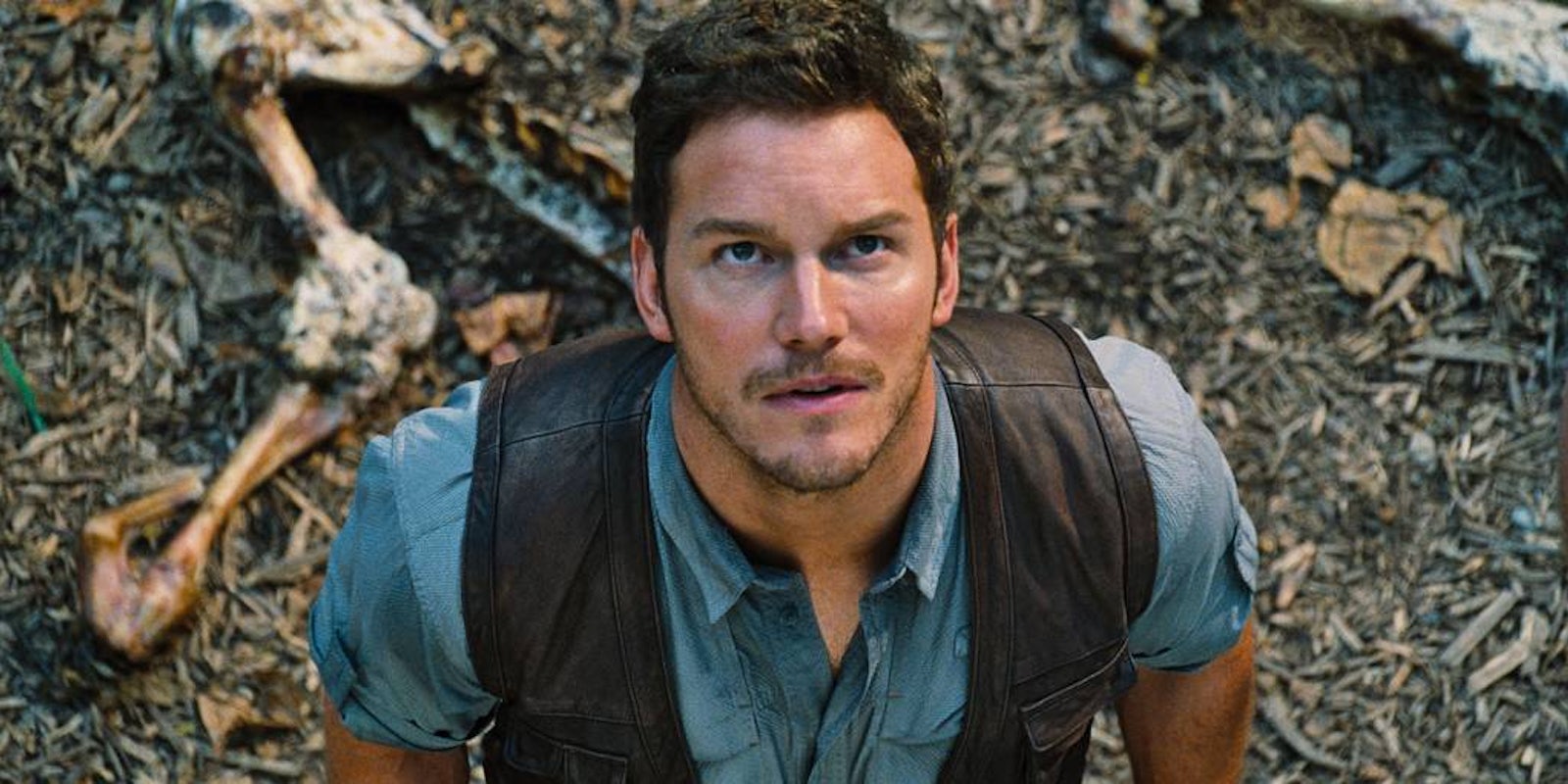

As the trailer progresses, Bryce Dallas Howard talks about creating the first genetically modified hybrid dinosaur. Chris Pratt responds with what everyone is probably thinking at that exact moment: “You just went ahead and made a new dinosaur? Probably not a good idea.” “Probably not a good idea.” When your lead character both accurately summarizes and criticizes the entire essence of your story in a general statement like that maybe—just maybe—you might want to start re-thinking some things.

Herein lays the problem with the concept of Jurassic World, at least at first glance. (The trailer dropped earlier this week.) The first Jurassic Park film did a rather successful job of displaying the ineptitude of Hammond’s theme park and why it was such a bad idea. The unsung hero of the first film, Goldblum’s Dr. Ian Malcolm—in a performance that defied button-up shirts—made an excellent point about why experimenting with evolution and then trying to commercialize it was inherently wrong.

In a way, Malcolm’s criticism of Hammond’s flagrant monetization of Jurassic Park could be seen as an indirect metaphor for the entire franchise—and every other franchise in Hollywood.

To quote Malcolm: “You stood on the shoulders of geniuses to accomplish something as fast as you could, and before you even knew what you had, you patented it, and packaged it, and slapped it on a plastic lunchbox, and now, you’re selling it.” The Jurassic Park series was probably something that was never intended to be a huge franchise, but before Universal (the company that finances and distributes the films) had any idea what Jurassic Park was, they were patenting it, packaging it and slapping the Jurassic Park logo on a plastic lunchbox—like the one I used to own when I was a kid.

Even Roger Ebert, who loved the first movie, quickly began to realize how the series was starting to go downhill beginning with The Lost World: “Many elaborate sequences exist only to be…elaborate sequences. In a better movie, they would play a role in the story.” By Jurassic Park III, the franchise was quickly becoming a parody, featuring a scene where Sam Neill’s Dr. Alan Grant dreams of a velociraptor—once the franchise’s most terrifying dinosaur—talking to him on an airplane. In his review of Jurassic Park III, Cinema Crazed’s Felix Vasquez Jr. wrote that the film was “a clumsy and poorly written farce with irritating characters I prayed for imminent death to arrive to.” That was one of the nicer things written about the movie.

This issue of franchise saturation actually extends far beyond the Jurassic Park series, where practically nothing is original anymore. In a piece for the Urban Times, Michael Osiyale reminds us how bad the problem is getting: “The number of sequels, franchise films, reboots and comic book and novel adaptations with a planned release since Winter 2013 to the end of 2015 is enormous and unprecedented.” Osiyale goes into further detail, talking about how the relentlessly churning machine that is Hollywood is drowning out films you wouldn’t even think to see, which was always the case before but is becoming even more prevalent now. While every once in a while we will have an original film from studios that isn’t based on a sequel, remake or established property, more times than not what you are watching is based on something you know.

There’s a certain formula to that—it’s the nostalgia that will create comfort and elicit a kind of emotional response, like Pavlov’s dog, that will make you want to see the fourth installment in an aging franchise. You might even think said franchise is getting stale, but that’s not the point. The point is studios want your attention and nothing gets someone’s attention more than the familiarity factor of someone—or something—you are already acquainted with. It’s like bumping into an old friend you haven’t seen in forever, but want to catch up with. You hope they are as friendly and likable as you remember, but sometimes they aren’t. Sometimes they are a pale comparison of the person you once knew.

I don’t have a problem with sequels; I even look forward to many of them. I do have a problem with films that don’t seem to merit the need of another chapter, like Jurassic Park. The original Jurassic Park was a classic, and one of those defining moments in blockbuster filmmaking. Director Steven Spielberg created a film that still holds up to this day. It was revolutionary in terms of both practical and digital effects and it took the whole blockbuster phenomenon in Hollywood one step further, much like the research in the film takes the concept of evolution one step further—or at least tries to.

The characters in the film, including Hammond, whose life’s work is built on the success of the park, never actually succeed. By the end of the first film, Dr. Grant scornfully tells Hammond, “After some consideration, I’ve decided not to endorse your park.” Even Hammond, in a bitter sense of defeat, admits “So have I.” You could get away with the devastation because the theme park wasn’t operational when the film began, so the deaths—although terrible—could be justified.

This is why in Jurassic World, I hope there is a justifiable reason for why anyone thought continuing what Hammond was trying to do was a good idea, at all. It could be argued—as Bryce Dallas Howard orates in the trailer—that years of genetic research have helped them come up with a solution for how they failed so many times before. However, by following that dino stampede of thought, it might also provide reasoning for why it also inevitably fails yet again, as witnessed in the trailer when things start to go awry.

What troubles me is that the mayhem witnessed in the first three movies was on a much smaller scale, but Jurassic World promises an entire island full of what seems like thousands of park attendees. Unfortunately, it fits with the logical progression of the series—which never should have been a series to begin with—and the natural need in Hollywood to make sequels bigger both in scale and destruction without taking the time to consider the impact it might have on the story.

That is, unless director Colin Treverrow has a trick or two up his sleeve. As I was watching the trailer, I noticed Judy Greer’s character tell her children, played by Ty Simpkins and Nick Robinson, to run if they see any dinosaurs. If the park is fully operational and presumably safe, why would she tell them that? It almost seems like the poor kids don’t even want to go to the park (they probably saw Jurassic Park III).

This might be far-fetched, but I’d almost be entirely on-board with the premise if the attendees know the park is dangerous and not completely safe. What if this is like a Hunger Games-style situation where the parents send their children off to this dino park knowing full well the risks as a rite of passage? Conversely, what if people get off on the thrill of almost getting their limbs torn off in this world? I’m sure many people would have a problem with those ideas, but at least it would be something new.

I like Treverrow a lot—his last film, Safety Not Guaranteed, was a quirky sci-fi film that no one saw. I liked that it was unpredictable and fresh, which is what I hope he instills into Jurassic World. Let’s face it: We’ve seen this story before, told numerous times with the same exact resolution. People think dinosaurs are like pets. People are wrong. People run from dinosaurs. People realize dinosaurs are not like pets and leave them alone. End of story.

Now, I don’t want to seem like I’m writing off the film just yet. I could be pleasantly surprised and the film could provide a decent explanation for why the people in charge felt the need to disregard the deaths, chaos and litany of bad choices that were made in the last three films. Despite all of this, I am still greatly looking forward to the film, mostly because I can’t get enough of Chris Pratt. I am sure Pratt will instill his character with his trademark sense of wit and charm that will probably overcome any of the film’s logic issues or script pitfalls, if there are any.

So, who knows, maybe Jurassic World will surprise. I will say this, though: If Chris Pratt’s character doesn’t have a scene where he dances to “Come and Get Your Love” with some raptors, then I’m going to be sorely disappointed.

Photo via Jurassic World/Trailer