BY DOMINICK MAYER

Let’s just get this one out there now before starting in on anything else in this piece: Pro wrestling both is and isn’t fake. It’s fake inasmuch as the outcomes are predetermined and the wrestlers trained for years in the art of not killing one another while projecting the illusion that they’re on the verge of killing one another. It’s real inasmuch as sometimes that goes wrong and somebody actually gets hurt, and realer in that matches aren’t predetermined move for move as the popular wisdom goes, and so professional wrestling (or wrestling, as it’ll be named henceforth for the duration of this editorial) is oftentimes closer to improvisational performance art than to even traditional theatre, its most common corollary.

What it is, however, is a form of popular entertainment with roots in the carnival. From its early days, wrestling in America has been perched as the common man’s entertainment, a medium that appeals to the senses above all and does so by appealing to the basest tropes and iconographies. In his writing on “The Spectacle of Wrestling,” Roland Barthes once spoke to this idea. “A boxing-match is a story which is constructed before the eyes of the spectator; in wrestling, on the contrary, it is each moment which is intelligible,” Barthes wrote. “The spectator is not interested in the rise and fall of fortunes; he expects the transient image of certain passions. Wrestling, therefore, demands an immediate reading of the juxtaposed meanings, so that there is no need to connect them.”

In less verbose terms, Barthes’ vision of wrestling is a form of spectator art that can be accepted with minimal thought process by the audience. The point is to take them away with sensation. This, however, has changed since this was written the better part of a century ago. Wrestling has become an art form with its own history, subcultures, shades of meaning, and seedy corners. Now, for many, part of wrestling fandom involves a hyper-awareness of everything from the functions of how matches work to the various backstage dealings that affect what happens during the show.

To return to the idea of seedy corners, wrestling unfortunately has a lot of those. Last week, Dion Beary wrote in The Atlantic about wrestling’s problems with race, its history and the ways in which that history continues to this day. His specific case study is WWE, given its status as the preeminent wrestling company in the United States. Beary writes, “There’s real-life drama and then there’s fictional drama. WWE’s response to allegations of racism, misogyny, homophobia, and ableism have always been the same: It’s fictional. But that excuse wears thin when the fictional racism lines up perfectly with the real-life racism.” Here, he could be talking about just about any major wrestling company in the televised history of sports entertainment—WWE’s preferred phrase for its offerings.

Though Beary’s article originally made the regrettable error of invalidating Dwayne “The Rock” Johnson as a former black world champion (he’s half black, half Samoan by heritage), he raises a great many points about wrestling in general and its problems with not only blackness, but any non-Caucasian race in general. Another problem which Beary only touches on tangentially, and one just as egregious in its own way, is its treatment of women. Debate on this has become more heated of late, which is heartening, but even in fan sanctuaries like the wrestling subreddit r/squaredcircle, some of the old rhetoric still exists. While a great many in that particular community are what you might call “enlightened” wrestling fans, people who appreciate it even as they acknowledge its sordid history, pictures of scantily clad female wrestlers frequently still attract the most attention on a given day of circulated links.

It’s not entirely their fault, though. Sure, it’s a poor attitude to have regarding an entire subset of the national wrestling population, whether fan or athlete, but it’s one that wrestling has historically fostered. From the early days of wrestling, warriors like Frank Gotch and George Hackenschmidt were billed as noble prizefighters, men among men who fought until they had nothing left. And to a point, early luminaries of the medium like the Fabulous Moolah were just as hard-nosed as their male counterparts. But over time, particularly with the coming of the 1980s, women’s wrestling became a sideshow attraction, as evidenced by GLOW (Gorgeous Ladies of Wrestling) and other such promotions that combined the hard-hitting in-ring action with plenty of side distractions.

And the mentality escalated from there. Where GLOW at least still centered on women wrestling, soon they became valets more often, or simply just eye candy. The saga of women’s wrestling from the ‘80s onward deserves a much longer history, but in summation, the brawling eventually gave way to T&A, not to be confused with TNA, the U.S.’s second-largest wrestling promotion today behind WWE. Through a mixture of the WWE’s, and at the time WCW’s, interest in all-around pageantry and the increasing button-pushing content of American independents like ECW, women’s wrestling returned to prominence again, but as a sexually titillating sideshow above all.

This isn’t to say that there weren’t good to great female wrestlers working at the time, but rather that the interest in them was as eye candy first and as athletes a distant second. Trish Stratus, a WWE Hall of Famer and one of the most beloved female wrestlers from the 1997-2002 boom period, was once stripped to her underwear in the middle of the ring on an episode of Monday Night Raw and told to bark like a dog. Other women during this time were part of mud wrestling matches, bikini contests, and “bra and panties” matches, which concerned stripping your opponent of their clothing in order to win. Mae Young, an octogenarian and storied ass-kicker from the Moolah era, was once involved in a storyline in which she embarked on a torrid love affair with a 400+ pound African-American weightlifter named Mark Henry, which culminated in her giving birth to a hand on live television.

I focus on WWE here because, for better and worse, they’re the definitive wrestling company. In the same way that Google has become the common household name for search engines, WWE defines wrestling in the U.S., and it’s the shorthand people use for describing wrestling to others, the first thing they show somebody who might be interested in it. Whether it’s the best thing is a debate for another venue and time, but the point is that when even the most respected, internationally-structured company in wrestling is engaging in this sort of behavior, it defines trends to everybody down the ladder. So, if WWE saw women as a sideshow attraction, it stood to reason that others did as well.

Beary acknowledges in his article that WWE has at least attempted to make strides toward repairing its sullied reputation of race-baiting, and likewise in recent years (particularly since its rebranding as PG-friendly entertainment) it’s moved away from female wrestlers as a sexually gratifying component of the show—sort of. While the sexuality isn’t anywhere near as explicit, and the branding of the so-called “Divas division” has centered around the strong, powerful women on the roster, consider for a moment the Divas Championship, the highest-ranking title a female wrestler can currently win. Were you to draw parallels between it and a garish Daytona Beach tattoo, you’d hardly be off base.

And for WWE’s insistence that its female roster is as much a part of the show as any other, it traffics in the same problematic tropes that Beary outlines. The stars of the WWE-branded E! reality show Total Divas are portrayed both on the show and WWE’s own programming as shrill, catty careerists who use their feminine wiles to get their way. Women with non-normative physiques (by their standards, anyway) in recent WWE history like Molly Holly or Mickie James have tended to be written into storylines drawing direct attention to this, making them the subject of mockery. Sara Del Rey, one of the best female wrestlers in the country today, works for them as a developmental trainer but has yet to compete on TV.

Women’s wrestling, by and large, is the kiddie table of professional wrestling. It’s an attraction match, given a few minutes in the middle of the show whenever crowds need a breather from the action to let their attentions wander elsewhere or buy merchandise. The shows are literally structured as such; this year’s WrestleMania, the pinnacle event of WWE’s programming year, saw the one women’s match sandwiched between the end of the Undertaker’s illustrious winning streak and the main-event championship match. When the upgrade in visibility for female wrestlers from active humiliation is to visibility, it’s not really much of an upgrade. (This may seem like a notable position, to compete in the penultimate match at WrestleMania, but this is what’s commonly known as a “cool-down” spot, one that allows the crowd to regain its bearings after a big moment before the next one arrives. This is where Divas tend to exist on PPV run sheets on a monthly basis.)

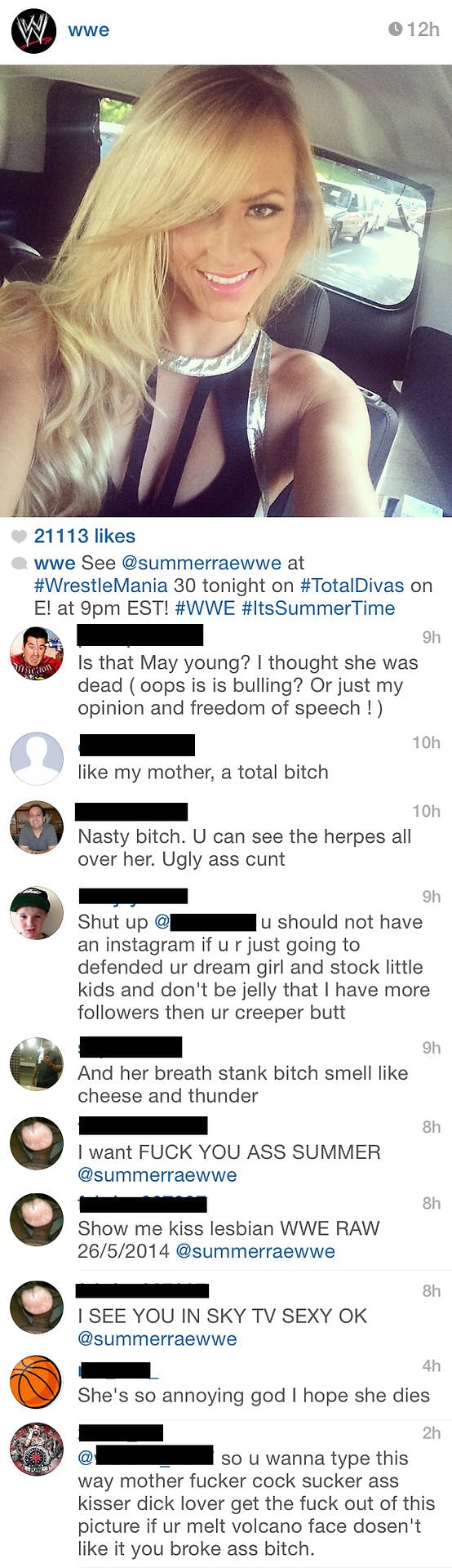

The trouble with these traditions is that the audience is changing a lot faster than WWE is—again, sort of. Since WWE still has a primarily male fanbase, you get things like the following, courtesy of the Tumblr page “S*it The Universe Says”:

The old attitudes exist with many fansbecause they’ve been conditioned from a young age to perceive women as non-entities, if not victims or shrews deserving of punishment. But at the same time, wrestling fandom has broken into the realms of fanfiction and other modern pursuits, Internet-enabled opportunities to engage with wrestling and add another level of self-awareness to a sport that’s long since started acknowledging its own tropes on-air. Fans can tweet their favorite performers, watch them toe the line of breaking kayfabe (storyline) on social media, and generally enjoy the same two-way engagement as other dedicated fandoms.

And luckily, in the era of the “smart mark,” the fan privy to the larger machinations of WWE beyond what it presents on camera, well-versed writers have been doing great, critical work of wrestling’s history of inborn misogyny. At With Spandex, Brandon Stroud and Danielle Matheson regularly offer some of the best wrestling criticism online today, and Matheson in particular has spoken powerfully on the need for increased visibility of women in today’s wrestling shows:

“First impressions are key, and when the first thing someone is told is that a human being is less than, that impression stays. It would be great to live in an entirely progressive fandom where women aren’t referred to as bitches and c*nts by merely existing within their gender, but again – we start out at zero. Whether a wrestler or a fan, it has been ingrained into the minds of most that we are a lesser. Opinions hold no weight, strength is relative, bitches can’t be trusted. Women are dumb sexual props, or conniving plot devices who should never be believed, especially if they dared to be in a relationship with someone.”

Matheson nails down exactly why WWE has to keep working, why it’s imperative that they work beyond Total Divas and two-minute matches that end in hair-pulling catfights. For a young, impressionable fanbase of a product that traffics in mythologizing, WWE has the opportunity to forge a new way ahead. There will always be something archetypically masculine about wrestling, but it can still be better. If building larger-than-life heroes is the name of the game, why can’t they be female sometimes?

More pragmatically, WWE can’t afford to continue alienating all but the most dedicated audiences. For all its overtures over the years toward the mainstream, the sort of press that more credible media receive has long eluded the company. And it’s because of this sort of thing that it does, and that it has a reputation as a low form of entertainment. With the recent high-risk launch of the WWE Network, a Netflix-style streaming service that offers much of WWE’s tape library for a cheap monthly fee, the company has essentially abandoned ship on Blu-ray and pay-per-view sales in order to centralize its programming within one hub.

The Network is WWE’s future, a way to reach out to consumers who might’ve fallen out of touch with their product. And based on recent quarterly losses, WWE is struggling to entice even its core fanbase to buy in. If the company is to survive one of its greatest gambles to date, it has to reach out to fans who might not be among those tuning in every week. It has to tap into the recent spate of ‘90s nostalgia and bring back fans who remember the halcyon days of Steve Austin and company. But those fans have changed, and to stay alive, WWE will eventually have to change with them.

Offering shows that don’t alienate a majority of the population might be a solid start.

Dominick Suzanne-Mayer is the coeditor of The Kelly Affair, and a staff writer at Consequence of Sound. He also hosts an open-mic at Uncharted Books in Chicago called Permanent Records, dedicated to the live sharing of embarrassing detritus from audience members’ younger selves.

Photo via Libertinus/Flickr (CC BY S.A.-2.0)