Leeza Pearson didn’t give much thought to packing a couple of Oreos in her four-year-old daughter Natalee’s lunch. Since Natalee’s preschool, the Children’s Academy in Aurora, Colo., doesn’t provide their students with lunch, Pearson assumed that what her daughter ate was up to her. She certainly didn’t expect the school to be inspecting the contents of Natalee’s lunchbox.

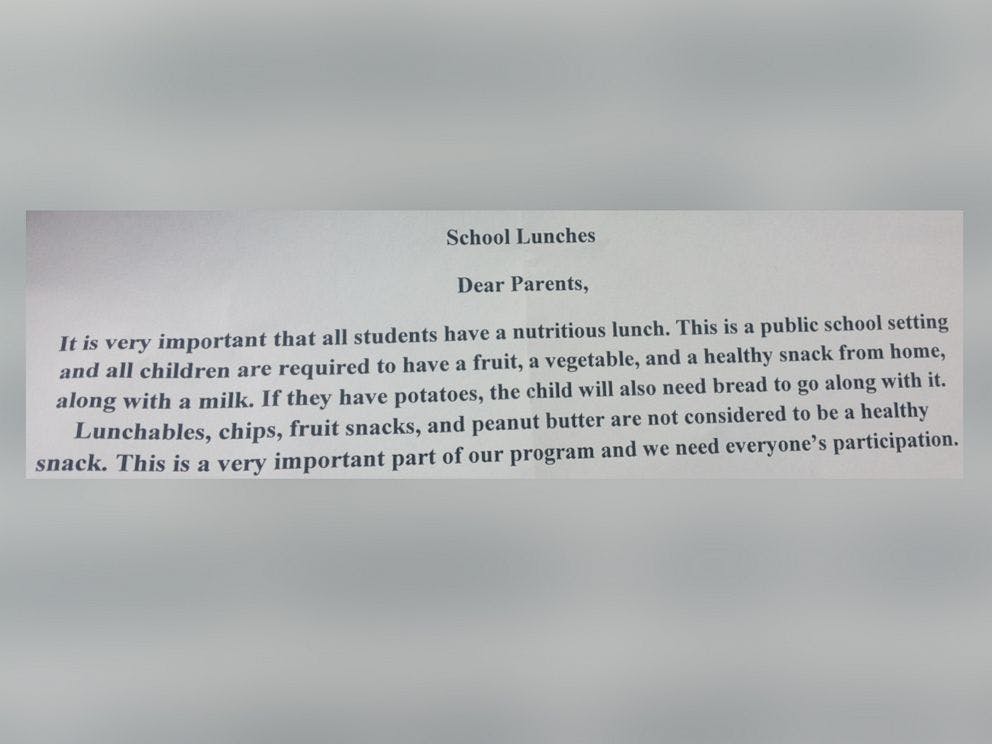

So she was understandably stunned when Natalee returned home that afternoon with a package of uneaten cookies and a note from the school, which later went viral. The note read:

Aurora Public Schools, which provides funding for some of the students at the Children’s Academy, has been quick to distance itself from the note. Patty Moon, a spokesperson for the school board, told ABC News that while they try do try to promote “healthy eating” among their students, sending notes home to parents about children’s lunches is not standard procedure. Moon said that their approach is meant to be supportive, adding that “we want to inform parents but never want it to be anything punitive.”

While the note is indisputably inappropriate, there is a larger conversation to be had here about how we broach the subjects of health and nutrition with children.

In a culture that is rife with fear-mongering about the so-called “obesity epidemic,” where shaming people for how the eat and the size of their bodies is a common and even celebrated practice, it’s unsurprising that schools are becoming more involved with their students’ diets. Of course, teaching children about health and food is nothing new. The food pyramid, “good” eating habits, and general nutrition have long been a part of the public school curriculum.

Recently, however, concerns about childhood obesity have lead to a push for schools to tackle food issues more directly. This has taken the form of serving more whole foods in school cafeterias, eliminating soft drink vending machines from school property, critiquing lunches that students bring from home, and even weighing students in class. While there have been some dissenters, public opinion has generally been in support of many of these practices.

https://twitter.com/MarcherLord1/status/588000957398659072

https://twitter.com/diinnaad/status/595276583658651648

https://twitter.com/KTHopkins/status/594541902495625217

The use of scare quotes in this article around terms like “healthy eating” and “obesity epidemic” is very deliberate. It’s important for us to understand that person’s health is something that can only be determined by a doctor, not a one-size-fits-all nutritional graphic, and calling obesity an epidemic is a complete misnomer.

It’s important for us to understand that person’s health is something that can only be determined by a doctor.

Language matters when we are talking about things that impact our people’s bodies. We should be especially leery of the terms “good” and “bad” when they are applied to food or eating habits. It is incredibly dangerous to assign moral value to food, especially with regards to children who are only just starting to learn about nutrition. Using loaded language like this when we discuss issues like diet and body size is contributing directly to the rise of eating disorders among teens and pre-teens.

Children process the world in a very black and white way. If they understand something to be bad, it will always be bad, no matter what the context. When children see educators, doctors, and even parents demonizing certain foods, they begin to develop a negative relationship with eating; just research has shown that fat shaming doesn’t help children lose weight, food shaming rarely leads to healthier choices. Even statements that are viewed as being neutral by our culture, such as an adult joking about a high calorie count or fat content, can be damaging to how a child views food.

How on earth do we ever expect children to ever develop a healthy relationship with food when we shame them for eating things that they enjoy?

Just research has shown that fat shaming doesn’t help children lose weight, food shaming rarely leads to healthier choices.

There’s nothing wrong with teaching children about how food helps them grow or explaining the roles that various nutrients play in their bodies. That being said, it is entirely possible to present these facts without making anyone feel bad about how they eat. Our aim should be to encouraging children to be in awe of all the amazing things their bodies can do, rather than presenting one specific size, weight, and diet as the ideal. Our schools should be focusing on sending positive messages about food and eating, rather than creating an environment in which certain foods are being branded as “bad” or “unhealthy.”

https://twitter.com/Ceraaa_Marieee/status/593533219439382528

https://twitter.com/FrancisDiet/status/593431605349322753

Obesity is not an illness, but eating disorders are. If our intent is to keep our children as healthy as possible, we should be working harder to prevent conditions like anorexia nervosa, bulimia, and other similar disorders. We know that these types of illnesses are chronic, difficult to treat, and can result in death or very serious complications, so why are we fostering an environment in which eating disorders thrive?

There is nothing to be gained by making children feel bad about what they eat. There is also no benefit in shaming parents for what they feed their children. The results of both of these tactics will only increase poor body image and self-esteem in children. Let’s break this vicious cycle and instead teach kids to love their bodies. There is no better—or healthier—gift that we can give our children.

Anne Thériault is a Toronto-based writer, activist and social agitator. Her work can be found in such varied publications as the Washington Post, Vice, Jezebel, The Toast and others. Her comments on feminism, social justice, and mental health have been featured on TVO’s The Agenda, CBC, CTV, Global and E-talk Daily. She’s really good at making up funny nicknames for cats.

Photo via USDAgov/Flickr (CC BY 2.0)