It appears that Snowden season is approaching once again.

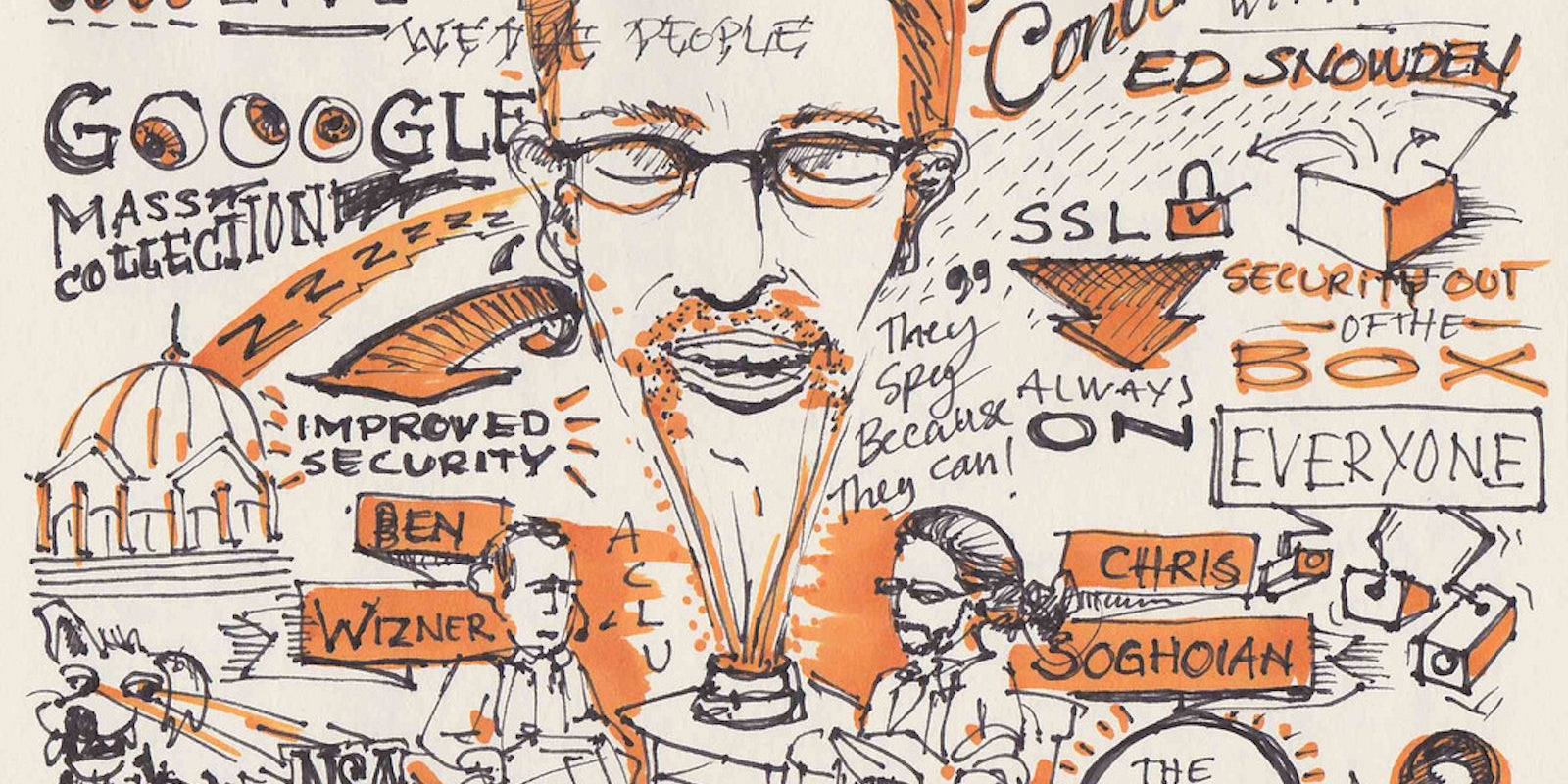

The controversial whistleblower made a surprise appearance via Google Hangout at SXSW this week, where his remarks proved captivating as always. Essentially a less flashy sequel to his ACLU speech from 2014, Snowden only spoke to a few people this time around, engaging in a conversation with a select group of leaders from America’s tech sector. In particular, he urged tech companies to become “champions of privacy,” suggesting that they use their power to help shield Americans from an increasingly watchful government.

In addition to speaking at SXSW in Austin, Snowden also said a few words at FutureFest in London, where he warned that massive surveillance won’t stop terrorism. In this instance, Snowden is absolutely correct, and it’s time we start heeding his advice.

At this point, the only people clinging to this idea is an effective is the NSA themselves. In 2013, NSA Director Gen. Keith Alexander went before the House Intelligence Committee to testify to claim that increased surveillance had helped to stop terrorist threats over 50 times since 9/11, including attacks on U.S. soil such as a plot to blow up the New York Stock Exchange and a defunct scheme to fund an overseas terrorist group.

Other witnesses in the same hearing also suggested that the Snowden leaks had harmed America greatly. “We are now faced with a situation that because this information has been made public, we run the risk of losing these collection capabilities,” stated Robert S. Litt, general counsel of the Office of the Director of National Intelligence. “We’re not going to know for many months whether these leaks in fact have caused us to lose these capabilities, but if they do have that effect, there is no doubt that they will cause our national security to be affected.”

However, the details the NSA provided in this hearing were somewhat hazy, and a closer look at the numbers indicates the benefits of increased surveillance may not be so clear-cut after all. Research from International Security found that out of the 269 terrorist suspects apprehended since 9/11, 158 were brought in through the use of traditional investigative measures. That’s almost 60 percent of all who were arrested. Meanwhile, 78 suspects were apprehended through measures which were “unclear” and 15 were implicated in plots but were not apprehended, while the remaining 18 were apprehended by some form of NSA surveillance.

Eighteen is no small number when you’re discussing matters of national security; however, the above statistics do not necessarily indicate that mass surveillance was responsible for the apprehension of these 18 terrorists or whether these suspects were detained under more traditional surveillance measures. Moreover, the evidence suggests that traditional means of combatting terrorism are more effective than surveillance when it comes to overall arrests.

Additional analysis from the New America Foundation further supports these findings. Examining 225 post-9/11 terrorism cases in the U.S., their 2014 report found that the NSA’s bulk surveillance program “has had no discernible impact on preventing acts of terrorism,” citing traditional methods of law enforcement and investigation as being far more effective in the majority of cases. In as many as 48 of these cases, traditional surveillance warrants were used to collect evidence, while more than half of the cases were the product of other traditional investigative actions, such as informants and reports of suspicious activity.

In fact, New America determined that the NSA has only been responsible for 7.5 percent of all counterterrorism investigations and that only one of those investigations led to suspects being convicted based on metadata collection. And that case, which took months to solve, as the NSA went back and forth with the FBI, involved money being sent to a terrorist group in Somalia, rather than an active plan to perpetrate an attack on U.S. soil.

According to the report’s principal author Peter Bergen, who is the director of the foundation’s National Security Program and their resident terrorism expert, the issue has less to do with the collection of data and more to do with the comprehension of it. Bergen said, “The overall problem for U.S. counterterrorism officials is not that they need vaster amounts of information from the bulk surveillance programs, but that they don’t sufficiently understand or widely share the information they already possess that was derived from conventional law enforcement and intelligence techniques.”

Of course, even when all of the data has been collected, it still isn’t enough to stop a terrorist attack. “It’s worth remembering that the mass surveillance programs initiated by the U.S. government after the 9/11 attacks—the legal ones and the constitutionally dubious ones—were premised on the belief that bin Laden’s hijacker-terrorists were able to pull off the attacks because of a failure to collect enough data,” asserts Reason’s Patrick Eddington. “Yet in their subsequent reports on the attacks, the Congressional Joint Inquiry (2002) and the 9/11 Commission found exactly the opposite. The data to detect (and thus foil) the plots was in the U.S. government’s hands prior to the attacks; the failures were ones of sharing, analysis, and dissemination.” So once again, we see that the key is not collection, but comprehension.

If all of this still doesn’t seem like enough evidence that mass surveillance is ineffective, consider that a White House review group has also admitted the NSA’s counterterrorism program “was not essential to preventing attacks” and that a large portion of the evidence that was collected “could readily have been obtained in a timely manner using conventional [court] orders.”

But mass surveillance isn’t just the United States’ problem. Research has shown that Canada’s Levitation project, which also involves collecting large amounts of data in the service of fighting terrorism, may be just as questionable as the NSA’s own data collection practices. Meanwhile, in response to the Charlie Hebdo attacks in Paris, British Prime Minister David Cameron has reintroduced the Communications Data Bill, which would force telecom companies to keep track of all Internet, email, and cellphone activity and ban encrypted communication services.

But support for this type of legislation in Europe doesn’t appear to be any stronger than in North America. Slate’s Ray Corrigan argued, “Even if your magic terrorist-catching machine has a false positive rate of 1 in 1,000—and no security technology comes anywhere near this—every time you asked it for suspects in the U.K., it would flag 60,000 innocent people.”

Fortunately, the cultural shift against increased data collection has become so evident in the U.S. that even President Obama is trying to get out of the business of mass surveillance; the president announced plans last March to reform the National Security Agency’s practice of collecting call records, which have yet to come to fruition.

Benjamin Franklin famously said that “those who would give up essential liberty to purchase a little temporary safety deserve neither liberty nor safety.” While this quote has been notoriously butchered and misinterpreted over the years, it has now become evident that we shouldn’t have to give up either of these things in pursuit of the other. The U.S. is still grappling with how to fight terrorism in this technologically advanced age, but just because we have additional technology at our disposal, doesn’t mean that technology is always going to be used for the common good. You may believe Edward Snowden to be a traitor or a hero, but on this matter, there is virtually no question: Mass surveillance is not only unconstitutional, it is also the wrong way to fight terrorism.

Photo via Fontourist/Flickr (CC BY 2.0)