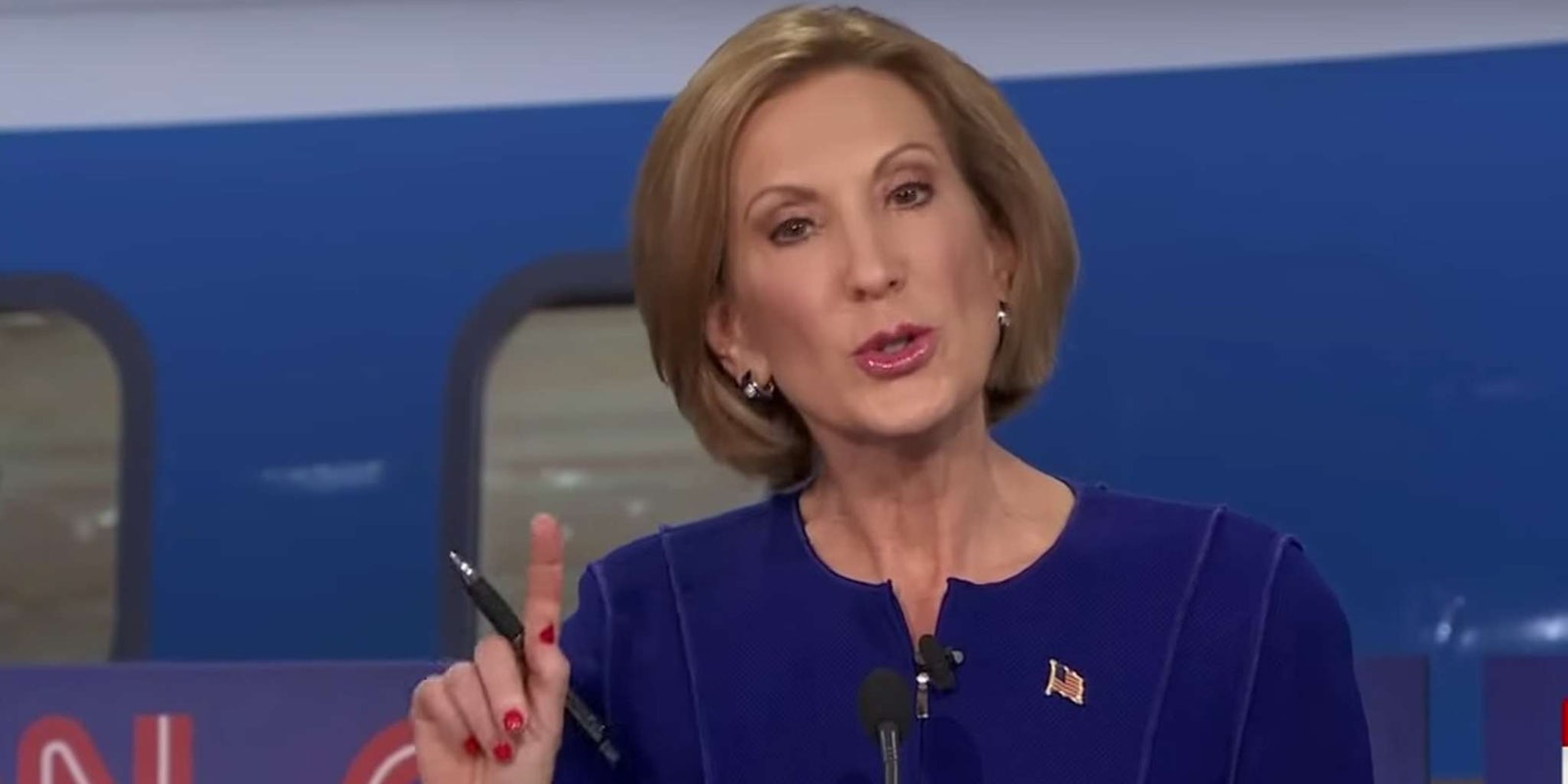

In the middle of her highly rated debate performance Wednesday, GOP presidential candidate and former Hewlett-Packard CEO Carly Fiorina invoked a tragedy from her own past in response to a question about drug legalization.

After a squabble between former Florida Gov. Jeb Bush and Kentucky Sen. Rand Paul about the supposed hypocrisy of Bush’s anti-pot laws (given his admitted use of the drug in his youth), Fiorina cited the 2009 death of her daughter Lori Ann Fiorina to a prescription pill overdose. “I very much hope I am the only person on this stage who can say this, but I know there are millions of Americans out there who will say the same thing,” she said. “My husband Frank and I buried a child to drug addiction. So, we must invest more in the treatment of drugs.”

However, after sharing her family’s grief, Fiorina continued, saying “we are misleading young people when we tell them that marijuana is just like having a beer. It’s not. And the marijuana that kids are smoking today is not the same as the marijuana that Jeb Bush smoked 40 years ago.” Bush, himself, conflated weed with heavier drug use by citing the recent wave of heroin overdoses in New Hampshire in response to a criticism of Florida’s marijuana laws.

The death of Lori Ann Fiorina is an immense tragedy, the kind of loss that has sadly become more common each of the last six years among American families. Her daughter’s death as an example in this particular conversation, however, is problematic. It conflates the kind of addiction that took the life of Fiorina’s daughter with marijuana, a dangerous confusion for the millions of Americans struggling with addiction. Lori Ann Fiorina died in 2009, the same year prescription drug deaths first overtook traffic deaths. The current addiction crisis is a national terror on families—and unnecessarily injecting marijuana into the conversation diverts focus away more pressing issues in the War on Drugs.

To be clear, contrary to what candidates like Fiorina imply, marijuana is not dangerous. In a multi-university paper published in February, researchers found marijuana use safer than than cocaine, heroin, meth, prescription opioids—even alcohol and cigarettes. And study after study continues debunking the “gateway drug” myth, showing that in the vast majority of cases, marijuana doesn’t lead to heavy drug use.

When political leaders mistake marijuana for a toxic, lethal drug, they affect people—like Fiorina’s daughter—and hamper our ability to get them the help they may need.

But Fiorina’s remarks at the debate signal a far cry from her previous, relatively progressive stances on drug policy. Back in May, when announcing her presidential campaign, Fiorina rather boldly stated “drug addiction should not be criminalized” and defended “decriminalizing drug addiction and drug use” as the best way to help addicts. By bringing up the tragic loss of her daughter as response to a conversation about marijuana, she misleadingly conflated the dangers of pill and opioid addiction with the relative lack of danger associated with pot.

When political leaders mistake marijuana for a toxic, lethal drug, they affect people—like Fiorina’s daughter—and hamper our ability to get them the help they may need. According to the National Institute on Drug Abuse, deaths from prescription pill abuse have more than doubled in the last decade. Roughly 1.9 million Americans live with prescription drug addiction, and six of them die every hour. It is an emergency that shouldn’t have to compete for attention and resources—especially not with something as relatively harmless as marijuana.

There’s an atrocious amount of money spent fighting marijuana compared to its actual societal harm. According to Harvard economist Jeffrey Miron, marijuana prohibition costs state and federal government $20 billion to enforce each year. According to a 2010 study by the American Civil Liberties Union, cracking down on marijuana can cost most states as much as $3.6 billion. These figures don’t account for the revenue that could be generated if more states moved to legalize, regulate, and tax the sale of marijuana. In Colorado, where the drug is legal, the funds benefit the state public schools, bringing in $70 million in tax revenue last year—more money than levies on alcohol sales.

Instead of taking a reasoned approach, most political leaders keep missing opportunities both for economic development and to substantively address the addiction crisis. But others are managing to do their part. In Massachusetts, Gov. Charlie Baker pledged to increase resources available to hospitals and police to help fight addiction and prevent overdoses—1,000 of which happened in his state last year. Over in Maryland, police officers and emergency responders in Baltimore have been equipped with Naloxone, a new drug that reverses an opioid overdose, a la Uma Thurman’s role in Pulp Fiction.

Addiction has become so common in New Hampshire that primary voters have directly confronted candidates on the issue.

And as Jeb Bush noted, addiction has become so common in New Hampshire, primary voters have directly confronted candidates on the issue. Democratic candidate Hillary Clinton held a town hall last month to hear the stories of just a few of the 46 percent of people in New Hampshire who are or know somebody who is struggling with addiction. Speaking to a different crowd, even New Jersey Gov. Chris Christie called addiction “the biggest problem not only facing this city but the state of New Hampshire and this country.”

Christie, like Fiorina and Rand Paul, believes the best fight against the crisis is not through the criminal justice system but through recovery and mental health. But when the candidates convey that marijuana use is as pressing an issue as opioids, they are arguing for resources to be taken away from treatment centers, and instead redirected toward an otherwise-pointless battle against weed.

I have no doubt that Fiorina has good intentions in fighting against all forms of drug use, and one can only imagine how invested she is in solving the addiction crisis—especially given her family’s tragic loss, one that also hits home for me personally. When I was 18, I lost my mother to an opioid overdose, after watching her struggle with addiction my entire life. I know the pain of losing someone to such an insidious evil.

And what my mother and Lori Ann Fiorina needed was a society that cared enough about the sick to make them healthy again, that knew the difference between a criminal act and a disease. Millions of Americans need that treatment today—and none of them deserve stigma, criminalization, or having resources taken away by something as relatively innocuous as pot.

Gillian Branstetter is a social commentator with a focus on the intersection of technology, security, and politics. Her work has appeared in the Washington Post, Business Insider, Salon, the Week, and xoJane. She attended Pennsylvania State University. Follow her on Twitter @GillBranstetter.

Photo via CNN/YouTube