BY KEVIN HOGAN

On the morning of August 19, I woke up early and went online to check the news. A headline in the business section caught my eye: “Ashley Madison infidelity site’s customer data ‘leaked.’”

A chill crept over me. I ran to the bedroom, where my wife was just waking up. She must have recognized a familiar look on my face, because she immediately reached for my hand and asked what was wrong.

“People are going to die,” I whispered to her, dreading the words as I said them.

A week later, I read of the first suicides allegedly related to the infidelity site’s security breach. And that’s when I realized that as many as 37 million people in more than 50 countries around the globe would be waking up to a bitter reality that I’ve lived with for almost four years: wearing the equivalent of a digital scarlet “A.”

The reference, of course, is to Nathaniel Hawthorne’s The Scarlet Letter: A Romance. Set in 17th century Puritan New England, the story’s protagonist, Hester Prynne, is forced to wear a scarlet “A” in public to identify her as an adulteress.

In a matter of moments, an “A” was firmly affixed to me that will forever be a part of who I am.

But how is this fictional story relevant? Surely we’ve evolved far beyond Puritan times when public humiliation was deemed a fitting punishment for those whose actions conflicted with the community’s moral code?

In actuality, we haven’t, as I can share from experience. A successful English teacher for more than 20 years, my career was cut short on Nov. 29, 2011, when a Fox Undercover report titled “Kevin Hogan, the Porn Star Teacher” aired on primetime to approximately 53,000 viewers. In a matter of moments, an “A” was firmly affixed to me that will forever be a part of who I am. I acknowledge that my “A” stands for “adult actor” rather than “adulterer,” but the effects of my stigma—a married teacher, bisexual but publicly assumed straight, having done gay porn—proved to be as dire for me as for any character in a novel.

Interestingly, Hawthorne’s work happened to be one of the first mass-produced books in America, and the initial printing of 2,500 copies sold out in 10 days. Now leap to today, where in our hyper-connected world, a piece of information can spread through media and social media like wildfire. It can be true, half-true, or a total fabrication. But once it’s on the Internet, it’s forever searchable.

We know all too well that if our community uncovers our sexual secrets, our credibility in other matters is at stake.

And when that information is about you, the consequences can rip your life apart.

Let’s face it: When 37 million people sign up for an Internet site facilitating extra-marital hookups, you can hardly say infidelity is uncommon. Nevertheless, adultery is also something most people disapprove of; in fact, even in the U.S., it’s still a criminal offense in nearly two dozen states.

But though lust, fantasies, and fetishes are all intensely human, we tend to keep that part of our lives hidden from public view. Because we know all too well that if our community uncovers our sexual secrets, our credibility in other matters is at stake. We might become defined by that one piece of discrediting information. In short, we risk becoming stigmatized.

Stigmatization, whether it’s as an adulterer, an adult actor, or some other label, can lead to a lack of support, social isolation, and a severely damaged perception of self. In the worst-case scenario, it leads to suicide.

Each of those 37 million people whose personal details are now published on the Internet is at risk of becoming the subject of public scrutiny. Criminals are targeting them looking to steal their identities or blackmail them. Many could lose their jobs on grounds of moral turpitude. And their closest relationships, those with their partners, children, family, and friends, could be strained and damaged beyond repair.

Is it any wonder that to date, tragically, four suicides are allegedly linked to this event?

Ultimately, we all make our own choices and have to live with them, right or wrong, moral or immoral, responsible or foolhardy. But as recent events underscore, when published on the Internet, these choices can be scrutinized and judged on an unprecedented scale. When that happens, we’re no longer in control of how others perceive us. We’re only in control of how we perceive ourselves.

The teacher in me screams to impart one more lesson. It’s vitally important for us to note that Hester Prynne chose to not let her stigma destroy her identity. On the contrary, she created an exquisitely embroidered letter “A,” proudly embellished with gold thread, and stitched it onto the bodice of her dress. It was simultaneously an acknowledgement of her actions, a refusal to be ignored, and a rejection of the smothering of her passionate spirit by a stigmatizing community.

If you’re one of the 37 million, you could be in for a very difficult and painful time. With luck, you’ll have love and support to help you get through this. But even if you feel alone, stigmatized, and fearful, I encourage you to look in the mirror every day and see more than just the scarlet “A” on your chest. Look both deeper and beyond, and see the whole human that you are, with all of your qualities, bad and good.

If you’re not one of the 37 million, I encourage you to suspend your judgment when you encounter stigma. Remember: The next hack could expose something about your personal life. We’re all human, after all.

So reach inside yourself; find your compassion. And if somebody you know is a victim of a stigmatizing cyber attack, extend a helping hand. Who knows? Your hand could save a life, not to mention a family.

In my case, back in 2011, even while news cameras were still rolling, my wife was the first to reach out her hand to me. She, along with the others who followed, including many from the bisexual community, saved my life and made me proud of who I am.

For more information about suicide prevention or to speak with someone confidentially, contact the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline (U.S.) or Samaritans (U.K.).

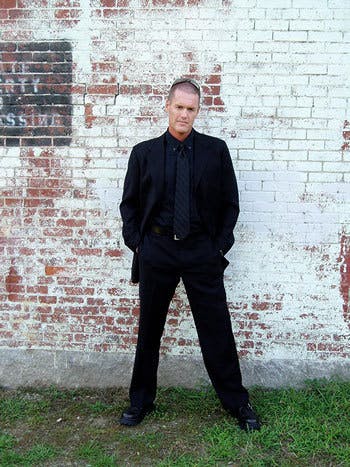

Kevin Hogan is an author, poet and LGBTQ activist. He’s currently working on a new book, Healing Stigma: A Survivor’s Guide to Repairing Identity in the Internet Age. Follow him on Twitter, @HealingStigma.

This article originally appeared at Huffington Post Gay Voices and has been republished with permission.

Photo via kumon/Flickr (CC BY 2.0) | Remix by Fernando Alfonso III