A national and international museum leader and scholar, Jim Cuno is the President and CEO of the J. Paul Getty Trust. Before joining the Getty, Cuno was president and Eloise W. Martin Director of the Art Institute of Chicago.

The digital world is both here to stay, but it’s also constantly changing. Keeping up with the pace of change is challenging and harnessing its potential can be frustrating. The biggest mistake many of us in the arts and humanities academy make is thinking of that potential only in terms of how we can use the new technology to more quickly and broadly disseminate information. The promise of the digital age is far greater than that. It offers an opportunity to rethink the way we do, as well as to deliver new research.

The history of art as practiced in museums and the academy is sluggish in its embrace of the new technology. Of course we have technology in our galleries and classrooms and information on the Web; of course we are exploiting social media to reach and grow our audiences [by tweeting about our books, our articles, including links to our career accomplishments on Facebook and chatting with our students online.]

But we aren’t doing that. We aren’t conducting art historical research differently. We aren’t working collaboratively and experimentally. As art historians we are still, for the most part, solo practitioners working alone in our studies and publishing in print and online as single authors and only when the work is fully baked. We are still proprietary when it comes to our knowledge. We want sole credit for what we write.

What we aren’t doing

Scientists, social scientists, and engineers don’t work this way. They work collaboratively and publish jointly and quickly for professional review.

The difference is stark when art historians (and I use this label to describe both curators in museums or professors in the academy) work together with conservation scientists on a common project. Art historians take their time and consult all accessible printed literature and visual comparisons before starting their first of many literary drafts. They want to integrate the results of the scientists’ work either in their written work (when the scientific findings elucidate a formal or historical point) or as a separate chapter or appendix in the final printed publication. They don’t want relevant scientific information to get out beforehand, either digitally or in print, even in highly specialized, scientific publications. They want their book’s publication to be the recognized event—not in small part because this is how career advancements are made.

Curators work in a similarly isolated fashion in terms of sharing their work. They research their collections, often resisting releasing their work until their research is complete. That the new technology allows for incremental publication—making it available for other specialists, even non-specialists, to read and contribute to (with new or corrected information)—is unexplored by them, or by the vast majority of them.

In short, humanists largely work alone and on timelines with long horizons. Scientists work together, experimentally, and publish quickly.

And all of this is only in terms, as noted above, of disseminating information. Scholars, curators and conservators of art are not exploiting the new technology to research differently.

What we should be doing

With new improvements in image recognition software, we should be experimenting with ways of compiling archives of formal and iconographic incidents across hundreds and thousands of images and then organizing and reorganizing them in ways that ask new questions and suggest new answers from cross-disciplinary and international perspectives.

Literary scholars have been doing this for some time already, compiling archives of texts and studying the incidence of particular words or phrases in the published work of specific authors or among published works of a particular period or in the changes in manuscripts from first drafts to final publication and then in misprints in each subsequent edition.

The power of our computers to store massive amounts of information and then order and reorder it in a near-infinite number of ways should be producing new paradigms in art historical research. Imagine what Panofsky or Aby Warburg could have done with our computers.

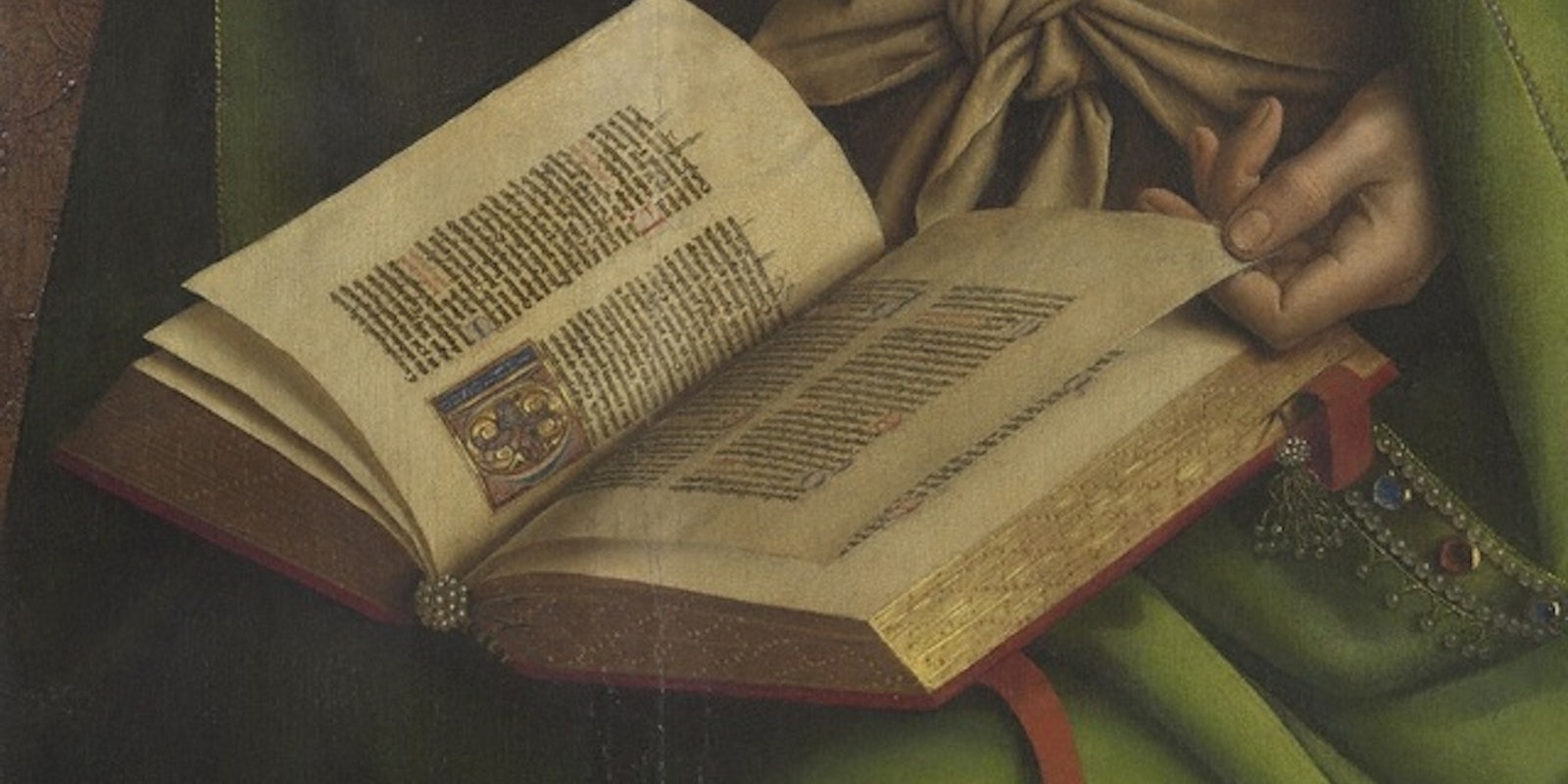

We should also be more open to open sourcing our projects. The recent Ghent Altarpiece Web application supported by the Getty Foundation is a case in point. Each centimeter of the multi-paneled, 15th-century altarpiece was examined and photographed at extremely high resolution in both regular and infrared light. The photographs were then digitally stitched together to create large, detailed images that allow for study of the painting at unprecedented microscopic levels, with access to extreme details, macrophotography, infrared, infrared reflectography and x-radiography of the panels. The Web application contains 100 billion pixels and the images and metadata are available free of charge as “raw” data to be used by any and all researchers, amateur as well as professional.

Unanticipated observations and interpretations will come of this open access, that’s for certain. And some of them will take root in the next generation of Van Eyck scholarship. Take, for example, Closer to Van Eyck, a project which documents in incredible detail not only images of the Ghent Altarpiece but extreme details, macrophotography, infrared, infrared reflectography and x-radiography of the panels (http://closertovaneyck.kikirpa.be.)

Where the future lies

One of the biggest challenges scholars and curators of contemporary art and architecture face currently, and will increasingly face, is how to store, retrieve, and investigate born-digital materials. The files are very large and have been created using different generations of software. How can we manage these files? And why should we be working alone in trying to solve this problem?

Surely our scientific colleagues and colleagues in governmental and commercial agencies have been struggling with these issues for years and have far more invested in finding answers to these questions than even we have. We should work together across disciplines to ensure the future of born-digital materials. And not just their future, but the future of our working with them on collaborative research projects, scholars with scholars and scholars with artists, architects, scientists, and other practitioners.

Humanists working alone and in isolation will inevitably be a thing of the past. It is time to embrace the present, let alone the future. As I said, the digital world is here to stay and constantly changing. We have to not only embrace it but help to shape it.