Ahmed Mohamed was arrested for crafting a sophisticated clock—one mistaken for an explosive—in hopes of impressing his teacher. A 14-year-old student in Irving, Texas, he looks like a dark-skinned version of Andre from ABC’s Black-ish. In fact, Mohamed is the son of a Sudanese immigrant—meaning that he is actually “Black-ish,” as well as Muslim.

On social media, there’s still debate over how Ahmed Mohamed’s racial identity should be characterized. When an incident of racist abuse befalls a “non-Black” minority, the story is captioned on social media with #BrownLivesMatter, as if #BlackLivesMatter does not include those victims. However, there is no need to deliberately keep our categories separate.

As the hashtag re-emerged, affirming that #BrownLivesMatter in response to the young man’s Islamophobic arrest, so did pictures of and information about the student’s family. Ahmed Mohamed’s father is an immigrant from Sudan, which is an indicator of Blackness similar to the many victims of police brutality and state violence mourned by #BlackLivesMatter to date.

Many have been quick to point out that Muslim Arabic-speakers from Sudan almost unanimously identify themselves as Arab—not Black. However, in the past 500 years since the beginning of the slave trade, Blackness has never been an opt-in or opt-out enterprise, regardless of religious affiliation, or even cultural and ethnic distinctions.

The diversity within both “Black and Brown” populations is undeniable and inevitable because race … was constructed without respect to scientific accuracy but for colonizer’s strategic gain.

Ahmed Mohamed is, thus, “Black-ish,” like all non-white people descending from colonized peoples and like his Sudanese ancestors—who, prior to British colonial rule, fought for resources along political lines. All the while, these people mingled and intermarried, only to be eventually divided “racially” for the purposes of European colonial conquest.

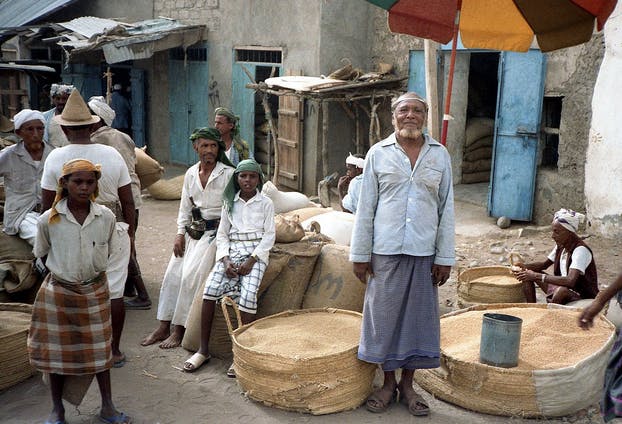

Colonial ideology was shaped by practices of power—and still has power in the world today. People, no matter how progressive or educated, still think of race in the colonial, pseudo-scientific, or genetic sense. It’s a way of thinking that’s grounded in artificial geographic lines, or expressed in the visibility of certain physical features, such as one’s hair texture or skin color. Thus, we are comfortable with the idea that someone of Habesha descent from the Horn of Africa should join the Black Student Alliance in college, while someone of a similar appearance—with ancestry from 200 miles away in Al Hudaydah, Yemen—should not.

But these features—which are typically thought of as expressive of “Blackness” or “whiteness”—all exist in Southeast Asia, in the Arab world, and throughout Africa, North and sub-Saharan, even in indigenous, non-settler populations. They even exist within the same families. The diversity within both Black and Brown populations is undeniable and inevitable because race—as a way to selectively and strategically interpret physical appearance—was constructed without respect to scientific accuracy. It was about exercising power for profit.

And ultimately, if Black and Brown are really distinct and completely separate, where do we draw the line? Skin tone? Language? Hair texture? Place of worship? National origin? Geography? Class?

That Ahmed Mohamed’s father is Sudanese and that Ahmed calls himself “Brown” complicates the notion of a real distinction between Black and Brown peoples.

The simple truth is that we don’t draw the line; the line has been drawn over 500 years of colonial expansion and domination. And in the context of such power and hegemony, who draws the line is more important than where the line is actually drawn—because it’s about the purported strategic advantage gained from doing so. At the invisible center of conversations about Black and Brown people is white society, which is served by our misconception of ourselves through colonial self-conceptions of difference.

Through violence and strategic racial policing, the legacy of colonialism has convinced people who lived together for millennia that henceforth we are fundamentally different and that our fates would never again be linked. But after Ahmed Mohamed was arrested by police in suburban Texas—a system whose agents also arrested and brutalized young Black people at a McKinney, Texas pool party—such ideology has never appeared more dangerous. More importantly, the idea that we are more different than similar is simply untrue—both politically and historically.

When we say that there are Black people and then there are Brown people, we are making the problematic claim that all Black people have the same experiences and history and that all Brown people have the same experience and history—and that these experiences rarely overlap. Nothing could be more untrue.

How could it be that our fates, in a country likely guided by a government under Donald Trump’s leadership, are not linked?

For example, being Latino/a doesn’t exclude the possibility of Black heritage. And the treatment of Latino/a people by police throughout the Western world is consistent with the Black experience. The discovery of mass graves along the border of Texas, and the state’s refusal admit that this was evidence of a crime against humanity, makes it clear that there’s a linked political fate between Central Americans and Mexicans who are subject to genocidal violence in order to keep America “white.”

These linkages are written into the history of America’s law enforcement—from police brutality to our penal codes. The Chinese Exclusion Act, the Indian Removal Act, Jim Crow, and the Black Codes that led to the Civil Rights Act all follow the same racial logic of white supremacy—maintaining that certain people (aka non-white people) oppose the very nature and values of American society. What then is our interest in accepting and reproducing such difference in our politics, and the way that we show our support and commitment to certain political ideas and values?

More than preserving dedicated political spaces, the division of non-White, Black, and Brown peoples into separate political groups who must be mobilized around separate chants, hashtags, and cultural advocacy groups, relegates us to such factions. By dividing us, Black and Brown peoples remain “minorities” where otherwise, in colonial history, we’ve always been the majority. Indeed, we have always been better together.

After all, when we say #BlackLivesMatter, aren’t we acknowledging that race is not about the width of someone’s nose, the curl of someone’s hair, the clothes you wear, or what we name our children—but the politics that enable people to construct and benefit from social systems of violence against others?

When people on the Internet post #BrownLivesMatter, they may be pushing back against any perceived racial exclusivity among some Black activists. But wouldn’t posting #BlackLivesMatter next to a story about any non-white kid who is carried out of school in handcuffs—for being too young, gifted, and non-white for this country’s comprehension—accomplish the same thing? If #BlackLivesMatter does not celebrate a global blackness, no matter what shade your skin color—and if #BrownLivesMatter does not stand for all people who are policed on the basis of their brown skin‚—do these hashtags mean anything at all?

Editor’s Note: The uppercase treatment of the identifier “Black,” a reference to Black Americans in this written work, is done in alignment with the cultural and academic positions of the author.

W.S. Paul Jackson is a writer, political theorist, and organizational community development specialist from Detroit who currently lives in Chicago, working in non-profit management to improve life in Black communities and neighborhoods and to raise consciousness about the systemic reality of oppression. He blogs at Blacobin.

Photo via Fox 4 News Dallas-Fort Worth/YouTube