Tommie King could be the next rapper to breakout from Atlanta. He’s well-connected, has obvious swagger, and he’s been quietly building a successful collection of singles on Spotify. His latest, “Eastside (feat. Cyhi the Prynce),” has already clocked more than 110,000 streams, driven largely by its placement on 14 independent playlists.

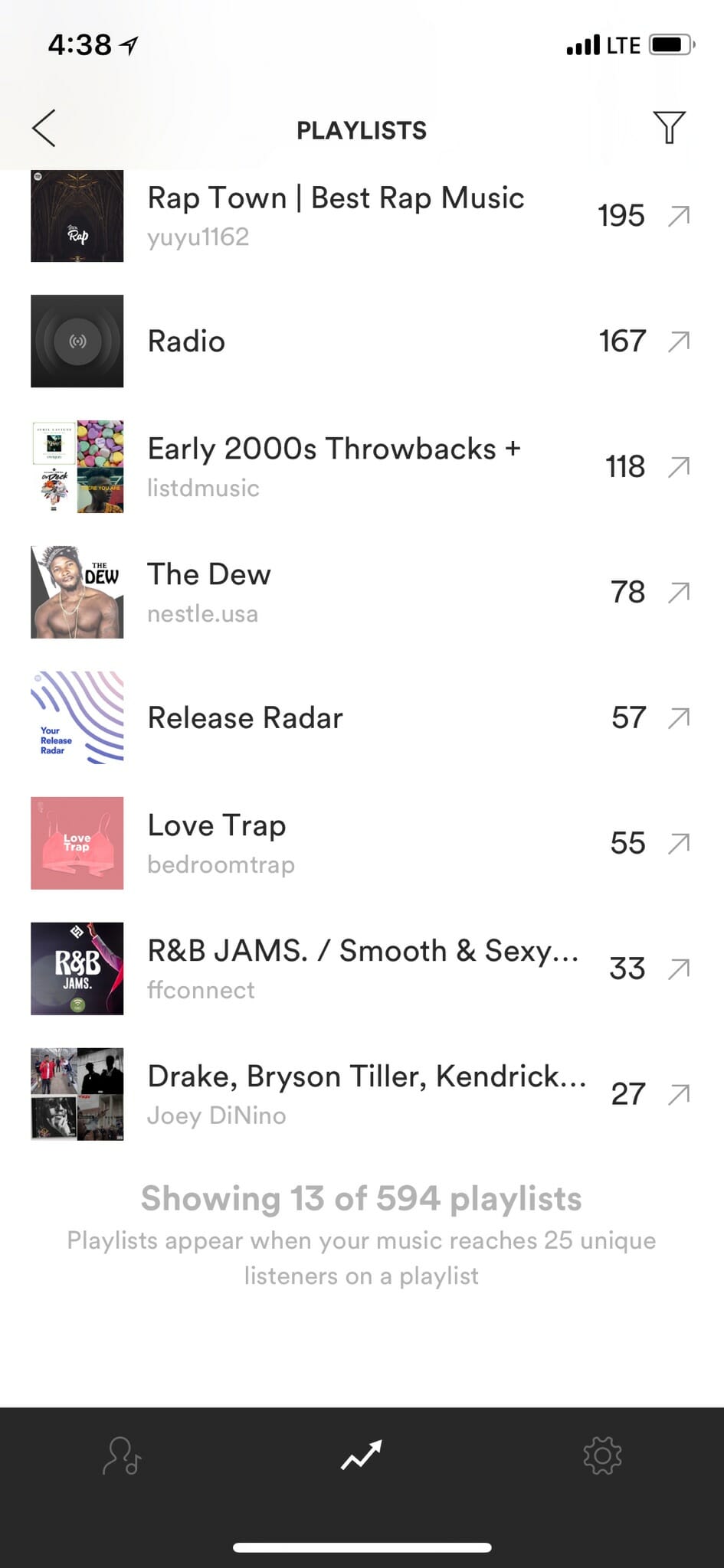

Gone are the days of hustling in parking lots, selling mixtapes out of the trunk of your car. In the modern music economy, streaming services account for nearly two-thirds of the total revenue generated by recorded music. Emerging artists are increasingly being tracked via big data. Spotify streams, YouTube views, Twitter interactions, and even Wikipedia searches are all being used to discover the proverbial next big thing. That’s why King’s manager has worked to land his music on a staggering 594 Spotify playlists to date.

“Without Spotify playlists, to tell you the honest truth, I wouldn’t feel like we were accomplishing much,” King tells me when I reach him at the phone number he lists publicly on his Facebook page. “Streams are now the only way to really reach people you otherwise wouldn’t be able to connect with. It gives you the ability to be played worldwide, which we’re doing quite well with.

“That’s everything nowadays.”

There’s just one catch: King essentially paid to be added to those Spotify playlists. He’s one of countless artists who have compensated curators to check out his tracks. Or in the case for some of his contemporaries, to be added to specific playlists. This is to gain valuable streams and attention.

The black market for Spotify playlists is booming. It’s cheaper than you might expect to hack the system—and if it’s done right, it more than pays for itself.

The rise of Spotify playlists

It’s impossible to overstate the value of Spotify playlists. The company dominates the streaming music market, with 159 million active users and 71 million paid subscribers. That’s nearly double Apple Music’s subscription base, according to a recent report in the Wall Street Journal.

More importantly, Spotify has made playlists its defining feature. CEO Daniel Ek said in February 2016 he wants “to soundtrack every moment of your life,” and he meant it. The company has created an official playlist for every conceivable occasion. Some are curated by its 150-person editorial staff and others algorithmically generated for specific genres and moods. Now, as Spotify noted in its SEC filing earlier this month, which valued the company at $23 billion, those official playlists account for nearly one-third of all listening on the platform, up from less than 20 percent in 2016.

The biggest of those playlists can essentially manufacture hits. A single add to Spotify’s influential RapCaviar, which boasts more than eight million followers, can result in hundreds of thousands of streams, depending on where it’s placed and how long it stays there. RapCaviar has been credited, for example, with making Smokepurpp’s “Audi” go gold, with 68 million streams and counting.

And that’s just one in-house playlist. Spotify boasts 2,500 of them, and they’ve become some of the most valuable real estate in the industry. Record labels and PR reps now pitch and collaborate with the tastemakers at streaming services the same way they have with radio stations and the press for decades.

“With so much of our revenue being directly generated from streaming services, it’s naturally a huge focus,” said Phil Waldorf, the co-founder of the indie label Dead Oceans and the head of global marketing for Secretly Group, its larger distribution network. “The added value [of a playlist add] is multi-faceted. On a basic level, the revenue generated from extra plays is a nice windfall. But, the hope is that the song performs well and then gets added on other playlists. A strong playlist add is a building block to more editorial support. And we hope some discovery happens along the way.”

The rising value of Spotify playlists has spurred a new form of payola. This is the decades-old illegal practice of paying for a song to be broadcast on the radio. Of course, massive amounts of money change hands behind the scenes. An August 2015 exposé by Billboard quoted an unnamed major-label executive who claimed playlist adds were being sold for “$2,000 for a playlist with tens of thousands of fans to $10,000 for the more well-followed playlists.”

Spotify responded by updating its terms of service to explicitly prohibit “selling a user account or playlist, or otherwise accepting any compensation, financial or otherwise, to influence the name of an account or playlist or the content included on an account or playlist.”

But the practice of paying for placement, as with other forms of payola before it, hasn’t died out. It’s just been remixed.

The new payola

In a matter of minutes and for a mere $2, you can pay to have your song considered by one of the 1,500 curators working on SpotLister, one of several new services that sells access to prominent Spotify users.

The site was founded by two 21-year-old college students—Danny Garcia, a guitar player at New York University, and a close friend who requested anonymity due to unrelated privacy concerns. They started a “private-for-hire” PR company in 2016 that offered “pitching services” to generate buzz on SoundCloud and, later, Spotify. The two would take on anywhere from 15 to 20 clients a month. Each pays anywhere from $1,000-$5,000 to secure prominent placement on playlists.

“We started out paying $5 [for a playlist add] and that worked in the beginning,” Garcia recalls. “When more people started getting into the game, you saw the prices starting to rise, and then the playlisters started seeing that they were relevant and worth a lot more. There are some playlists that have 90,000 followers that can charge $100-$200 for an add, all the way up to playlists with 500,000 who can charge $2,000 for one placement.”

Spotify, in a statement to the Daily Dot, said, “There is no ‘pay-to-playlist’ or sale of our playlists in any way. It’s bad for artists and bad for fans. We maintain a strict policy, and take appropriate action against parties that do not abide by these guidelines.”

Pay-for-play schemes, however, are absolutely taking place on Spotify. “I’ve had some ask for anything from $25 to $100,” confirms Cody Patrick, the owner of Organic Music Marketing, who manages Tommie King and other hip-hop artists in the Atlanta area. He’s deeply established in the local scene. His production company, Resolve Media Group, is responsible for nearly every notable rap video filmed in Atlanta in recent memory, including D.R.A.M.’s “Broccoli” and Migos’ “Bad and Boujee.” Patrick’s seen it all on Spotify.

“I’ve had some curators who run multiple playlists offer me monthly retainers to be in their playlists for a certain amount of time,” he says. “I’ve seen people offer levels: You pay this much in the top 10, this much to be in the middle, this much to be in the circulation, period.”

Personal outreach, though, is time consuming and often cost prohibitive. You have to not only identify target playlists but track down contact information and make introductions. Even then, there’s no easy way to tell if a playlist is open for business. Ignatious Pop, a Spotify user who’s garnered more than one million followers for his longform soundtracks for popular shows like Big Little Lies and Insecure, told me he’s “been offered plenty of cash for my playlists, profile, or just to add tracks to the playlists, which I have turned down every time.”

SpotLister aims to simplify the whole process, tapping into the network of contacts its co-founders created over the last two years. When you upload a track to the service, it gets analyzed by what it calls its Playlisting Indexing Algorithm. It uses Spotify’s API and Echo Nest to scrape the song’s characteristics. Then, it uses that metadata to identify the most appropriate playlists to submit to. That way an indie rock band isn’t wasting time sifting through EDM playlists (or vice versa).

The more followers a playlist has, the more it costs to be considered. A playlist with 100,000, Garcia says, takes nine credits, or $18, while a playlist with only 500 followers—the minimum to be included on SpotLister—costs just one credit, or $2. After each submission, playlisters have 72 hours to review a track—which involves not only listening to it but providing some level of feedback, which, in turn, is provided to the artist—to receive compensation. Playlisters receive $0.24 on the $1 from each reviewed submission, regardless of whether they decide to add the track to their playlist.

The more followers a playlist has, the more it costs to be considered. A playlist with 100,000, Garcia says, takes nine credits, or $18, while a playlist with only 500 followers—the minimum to be included on SpotLister—costs just one credit, or $2. After each submission, playlisters have 72 hours to review a track—which involves not only listening to it but providing some level of feedback, which, in turn, is provided to the artist—to receive compensation. Playlisters receive $0.24 on the $1 from each reviewed submission, regardless of whether they decide to add the track to their playlist.

After just five months, SpotLister claims to have access to 13,000 playlists with a cumulative reach of 11.7 million followers.

“We can’t make guarantees about getting a song on a playlist,” Garcia clarifies. “We’re paying the playlister to review the track, not to actually add it.”

Exploiting the system

There’s a fundamental problem with SpotLister’s model that might not be apparent at first glance. It also has nothing to do with Spotify’s terms of service. What matters about a playlist isn’t how many followers it has—it’s how reliable and engaged its listeners are.

That’s because it’s ridiculously easy to inflate numbers on Spotify.

Streamify, one of several services that offer phony streams, allows you to acquire up to two million plays at a time. In fact, it’ll give you 1,000 free streams just for signing up—and it works. Late last year, two Vice reporters in Denmark created a fake band called Cl1ckba1t. They created an unlistenable song and paid the service $40 to generate 10,000 streams. Their order was fulfilled in 10 days.

Likewise, playlisters often inflate their follower counts through what’s known as a followgate. This is a well-established technique in social media that requires a user to follow an account (or submit an email address) in exchange for something like a free download. As such, you might end up paying more to submit to a playlist that appears to have a ton of followers but is really just a ghost town.

“I’ve had to bite the bullet and find out how they really work,” says Patrick, who’s used no fewer than nine different Spotify services to bring attention to his clients. “It’s not hard to purchase fake followers for a playlist.”

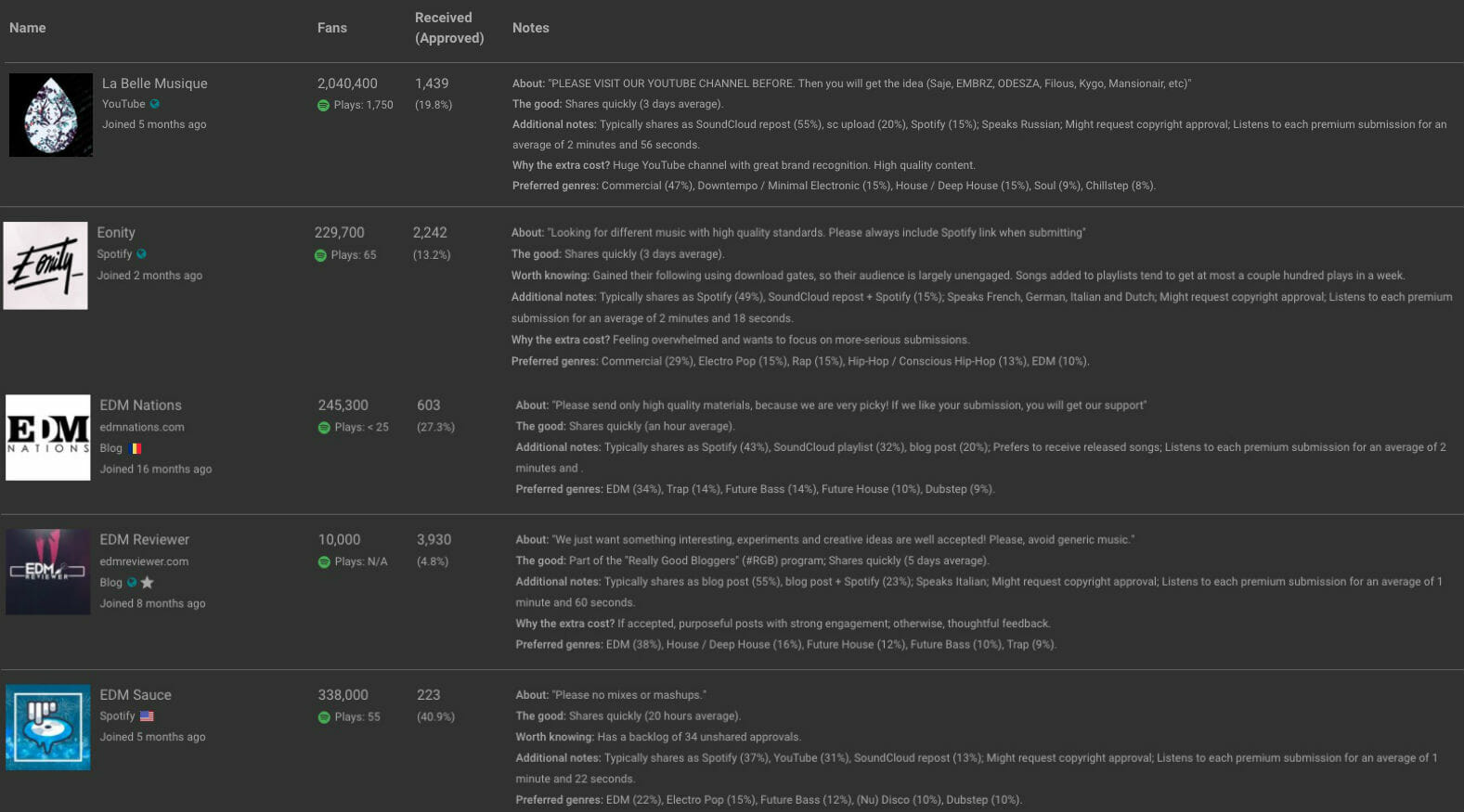

SubmitHub is trying to solve that problem. Jason Grishkoff, a former Google team member based in Cape Town, South Africa, originally created the service in late 2015 as a way for artists to send songs to his blog, Indie Shuffle. Now anyone who shares music with a sizable audience—bloggers, playlisters, SoundCloud channels, YouTubers—can use the service to solicit submissions.

Unlike SpotLister, users can submit tracks on SubmitHub for free—Grishkoff claims the site facilitates 10,000 submissions per day—but premium credits can be purchased to ensure feedback and that influencers listen to at least 20 seconds of each song.

“We quickly started to realize that many [Spotify] follower accounts weren’t legit,” Grishkoff says. “It gets tricky. There are some people who have 100,000 followers and 20,000 of them are real that they picked up a while ago, but in order to keep up appearances, they’ve been buying followers.”

Grishkoff developed an ingenious workaround. He asked SubmitHub artists who use Spotify to upload data from their dashboards—which reveal all of the playlists a song has been added to and how many streams that playlist has generated for it—and cobbled it together. The resulting database estimates how many plays a specific playlist is likely to produce. That information is included with details on a breakdown of a given playlister’s response rate and whatever information they’ve provided about what they’re interested in.

SubmitHub

SubmitHub

” class=”wp-image-382283″>

SubmitHub

SubmitHub

” class=”wp-image-382283″>Grishkoff is clearly proud of the service SubmitHub provides. He claims that influencers listen to two minutes of a song on average and that the overall rejection rate is above 90 percent. He’s convinced that the site’s influencers aren’t just in it for the money.

“I think if you asked any of these guys, ‘If I paid you a dollar, would you put me in your playlist,’ they’d tell you, ‘Dude, fuck off.’”

Grishkoff also argues there’s inherent value to the feedback that services like SubmitHub are able to facilitate, even if it’s crude or tossed-off.

“If you’re an early artist and you don’t want to throw down the money yet for a publicist, this is a good way to dip your foot in there and see if you have a shot or not,” he says. “It can be helpful to reach an audience but also for a bit of a reality check. You might not be destined for the success you think you are.”

The ripple effect

The real beauty of these Spotify services is that, when the system works, you can actually make your money back—and then some.

“You can hypothetically do that back-of-the-napkin math now,” Grishkoff says. “With [SubmitHub] you can say, ‘OK, it costs a dollar to send [this track to a playlister]. They’ve got a 15 percent approval rating, but if I’m one of those 15 percent, it looks like they get an average of 4,000 plays, so I might make $15 back.”

In other words, Spotify is inadvertently paying artists to cheat its own system.

That’s not the way the creators of SpotLister and SubmitHub see it, of course. They believe their services are leveling the playing field on Spotify, helping counter the dominance of major labels. UMG, Warner Music Group, and Sony Music Entertainment all hold equity in the service. Their artists, perhaps coincidentally, dominate most of Spotify’s most influential playlists. On average, three-fourths of the artists on the aforementioned RapCaviar, for example, belong to major labels. And what’s more, those labels’ playlists dwarf most other unofficial alternatives, especially Sony’s various Filtr playlists.

“We see ourselves as a solution to that problem,” says the other co-founder of SpotLister. “The major labels have so much influence over what goes into these major playlists now. We just want to give opportunities for up-and-coming artists to have that as well.”

Make no mistake, though: The end goal of using services like SpotLister is, in part, to end up on Spotify’s official playlists.

“I’m using Spotify as an algorithm,” King stresses. “To me, the importance of playlist adds is to get on the radar of official Spotify editors. As soon as you’re in a certain number of playlists, you start getting added to Release Radar and Discover Weekly [two algorithmically generated playlists created each week for subscribers], and you can build organic streams from there.”

That’s a common belief in the industry, one shared by Dead Oceans’ Waldorf, who, to be clear, has not used SpotLister or other comparable services for his artists. “[I]f a song or artist is repeatedly saved or listened to,” he says, “it’s more likely to pick up traction in the algorithmic playlists, which have their own positive impact on discovery.”

“That’s a really strong signal to Spotify,” adds Grishkoff, and one that Tuma Basa, the global head of hip-hop programming at Spotify, has confirmed informs the company’s playlists. “[W]e can see within our analytics if something is for real,” Basa told Digital Trends earlier this year. “That’s the beauty of our technology. It’s all right there. All facts. No guesswork.”

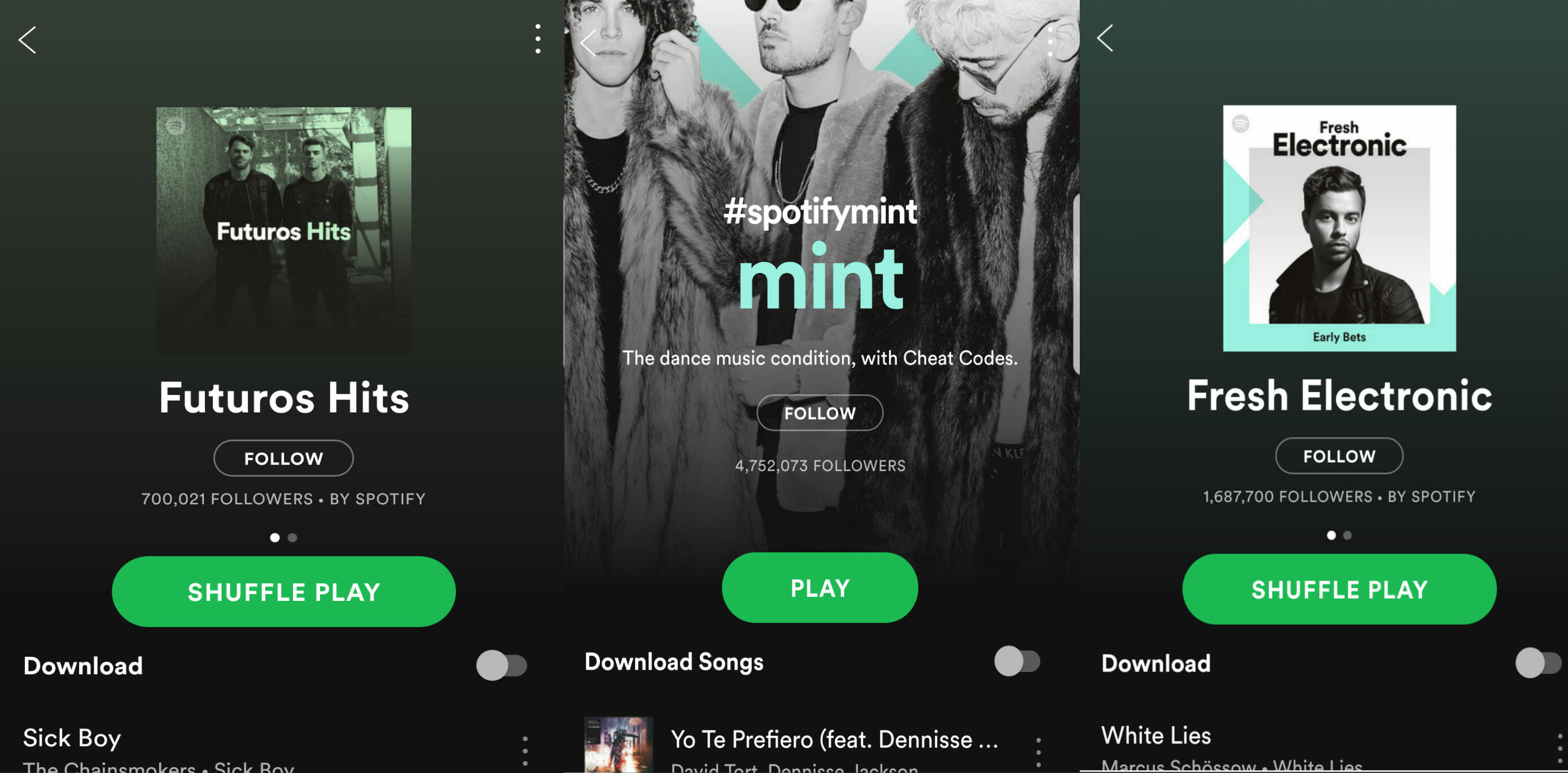

MaWayy has experienced that Spotify ripple effect first-hand. The electronic duo—Brian Way and Masoud Fuladi, who collaborate online and have never actually met in person—has “used pretty much every platform we found online,” MaWayy says via email. That includes SpotLister and SubmitHub. The former added their track “Wrong” onto 19 playlists in a matter of days, generating 800,000 plays in the process. That momentum caught Spotify’s attention, and the single was subsequently added to three of Spotify’s biggest electronic music playlists: mint, Fresh Electronic, and Furutos Hits. “Wrong” is now quickly approaching 1 million streams at the time of publication.

MaWayy has experienced that Spotify ripple effect first-hand. The electronic duo—Brian Way and Masoud Fuladi, who collaborate online and have never actually met in person—has “used pretty much every platform we found online,” MaWayy says via email. That includes SpotLister and SubmitHub. The former added their track “Wrong” onto 19 playlists in a matter of days, generating 800,000 plays in the process. That momentum caught Spotify’s attention, and the single was subsequently added to three of Spotify’s biggest electronic music playlists: mint, Fresh Electronic, and Furutos Hits. “Wrong” is now quickly approaching 1 million streams at the time of publication.

“The speed and reliability of this process is amazing,” MaWayy wrote. They noted that some of the larger playlists they were added to seemed buoyed by fake followers, but they’re still satisfied with the results. “We like how easily we could get our music heard by all these playlist curators.”

If anything, it’s almost too easy. These third-party services have found a backdoor into the valuable world of Spotify playlists, and anyone with some budget to spare can potentially be granted access. That has the potential to dramatically alter the way independent music gets promoted online, and it leaves Spotify in a vulnerable position. After all, there’s no easy way to determine what tracks benefitted from pay-to-play schemes and which ones curators just genuinely liked.

“It’s dangerous when you start to look at the potential to lose what really gives the culture its weight,” says Tommie King, the Atlanta rapper. “Now if you have the right amount of money, you can just do it.”

That doesn’t mean he regrets using the service.

“It’s not really a big secret,” King says. “Everything costs money.

“It’s just part of the game.”

Update 8:52am CT, March 17: SpotLister shutdown on Friday. On its website, the company, which changed its name to JamLister in attempt to distance itself from Spotify, provided the following statement:

“Spotify has deemed our platform to be non-compliant of Spotify’s Term of Use and despite all of our efforts to rebrand and comply with their requests, our API key has been deactivated so we will no longer be able to operate on our platform. Therefore, we will begin providing refunds to everyone for their SpotLister balances, These refunds will be calculated taking into considerations submissions that were already reviewed and completed.”

Editor’s note: This article has been updated to clarify SpotLister’s revenue model.