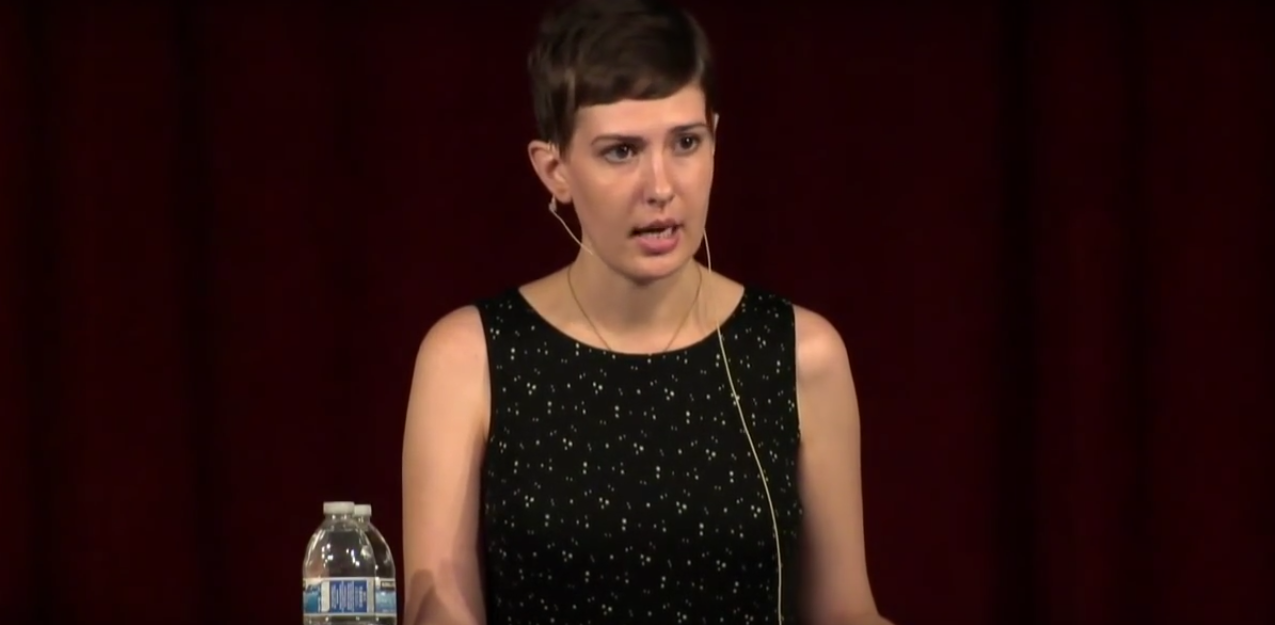

The culture wars have shaped both Patricia Lockwood’s career and her personality. The famed poet and tweeter first rose to prominence outside of the poetry world in 2013 when the Awl published “Rape Joke”—an explicit and honest prose poem fighting the mistaken notion that sexual trauma can ever be considered a laughing matter. The response to “Rape Joke” landed her a book deal, resulting in her 2014 collection Motherland Fatherland Homelandsexuals. Lockwood had since been dubbed “the poet laureate of Twitter” and “the smutty metaphor queen of Lawrence, Kansas.”

Lockwood herself was likewise born into the fire of a moral argument. As detailed in her new memoir, released this week through Riverhead, Lockwood and her siblings were raised by parents uniquely embroiled in the orthodox world of Catholic activism. With the supremely fitting title Priestdaddy, Lockwood’s memoir serves a story of returning home both humorously wrought from the author’s love for her family yet painstakingly devoted to the complexities of faith and trust.

Catholicism a fine and fertile topic for Lockwood’s writing style which, for the uninitiated, simply shimmers with her epic talent. Lockwood spins a joke or simile with every exhale. She is the kind of writer who creates instantly memorable images that dance across water while hiding—if not completely abstaining from—effort or pretension.

Much of Priestdaddy involves Lockwood’s own commentary on Catholic faith and worship, from the repressed sexuality of a seminarian to the culture between bishops and priests like her father. Priestdaddy is dense with Lockwood’s own wit and thinly veiled agnosticism. For the benefit of the reader, she takes an outsider perspective on a wildly misunderstood world, and does so with delicate yet biting affection.

Consider an early portion of the memoir in which a 19-year-old Patricia invites over her to-be husband Jason, whom she met online. She prepares Jason for her religious household—which is literally contained within a convent—by describing Catholicism as “First off, blood. BLOOD. Second of all. Thorns. Third of all, put dirt on your forehead.” She describes the Catholic image of Jesus as “so gentle that sheep seem like demented murderers in his presence,” yet “he also always looks like one of those men in a headache commercial, because you’re causing him so much suffering when you cuss.”’

Such observational prowess has made Lockwood a star of “Weird Twitter,” where she indulges in absurdist sexting and perfecting the art of dry humor. “[S]o is paris any good or not” she tweets to—who else—the Paris Review. Yet it is when she turns this subtle weaponry against the many contradictions, dangers, and fallacies that dominate her father’s faith that Lockwood truly unloads the clip.

A former Cold War submariner who found faith after watching The Exorcist, Lockwood describes her father as devout and garrulous. “He could argue the numbers off a clock and the print off a newspaper,” writes Lockwood, “and now he argued himself into orthodoxy.” He is a lover of beef jerky and cream liqueurs, a man who listens to Bill O’Reilly and Rush Limbaugh simultaneously. He is a traditionalist who shouts along to the catchphrases of action movies.

Priestdaddy is full of such humorous, coming-of-age familial anecdotes—her father teaching her to swim by throwing her into the pool, her mother and herself debating which bodily substance stained a hotel bed—which are balanced by the author’s more serious understanding of Catholicism as an institution. When a priest in her father’s circle is accused of sexually abusing a child, for instance, Lockwood notes the poisonous effect of institutions on people’s moral understanding.

“A we is so powerful,” she says, “Its hands are full of the crispest and most persuasive currency… The we closes its ranks to protect the space inside it, where the air is different. It does not protect people. It protects its own shape.”

Such starkness also comes in Lockwood’s remembrance of being taken to pro-life protests where her own impressionable mind watched her parents and other adults bombard abortion clinic patients with placards of bloodied fetuses. After hearing a woman in the movement suggest she would rather die than abort a pregnancy, a young Lockwood is passed on opaque notions of womanhood and motherhood. “It meant that childbirth turned a mother into something with twenty claws, and she would turn them on herself if she had to,” she notes.

This dichotomy between fond memories of her family and the nightmarish moral conclusions of the church which raised her serves Priestdaddy well, taking what could be a liberal feminist millennial’s takedown of an easy target into an honest and sometimes brutal portrait of her father and the institution to which he has devoted his life. Lockwood’s own waxing and waning faith sits just on the outside of it, as liquid and complicated as the concept of eternity itself.

Through her poetry and Priestdaddy, Lockwood is the kind of natural talent that makes you wonder whether writing can really be taught at all or if it comes to you like a revelation. Lockwood answers this question by noting how a belief in an omniscient god discourages the observant mind: “How could I be sure I was telling the truth about myself when he claimed to know me better than I did?”

Lockwood finds and is defined by writing, the only sure thing in a lifetime spent wriggling free of the constricting dogma of her family. “Of course that is what I would grow up to do,” she says. “Of course I would find a way to live within that sure, swift, unassailable answer.” Live within it she does, and Priestdaddy is about the question that led her to it.