It’s important to understand in watching Netflix biopic Roxanne, Roxanne, that the film’s subject—groundbreaking Queensbridge, New York rapper Lolita Shante Gooden, aka Roxanne Shante—wasn’t a multi-platinum artist. She wasn’t Nicki Minaj, Lauryn Hill, or Missy Elliott, or someone with a big, catchy Cardi B-like single.

She was so much more than plaques, splashy videos, and world tours.

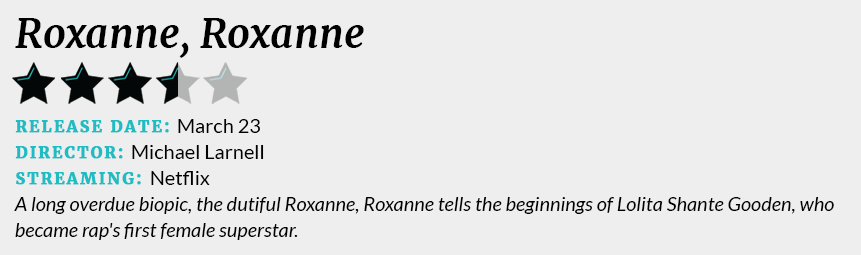

Shante’s overarching impact on hip-hop is more inferred than realized within the Michael Larnell-directed film. She was significant in a way exceedingly few women rappers have been since, recognized openly and widely as a lyrical monster of her time, a giant on par with—or better than—any male rapper.

Where the plot doesn’t begin is essential. In 1984, while doing laundry, a 14-year-old Shante (Chanté Adams, in a fantastic performance) put down one of the rap’s great verses for soon-to-be legendary producer Marlon “Marley Marl” Williams. “Roxanne’s Revenge” was the response record to U.T.F.O.’s “Roxanne, Roxanne” that would become a genre-changing underground single. The song would sell 250,000 copies, generating dozens of 12-inch singles responding to this rivalry. The “Roxanne Wars” pushed competitive rap forward in ways unseen since. The film notes Shante’s competition with frenemy Sparky D, never getting to the more prominent battle with the U.T.F.O.-backed Real Roxanne.

But Roxanne, Roxanne elects to begin from a string of losses. A young Shante witnesses the struggles of her mother Peggy (played with a unique rawness by Nia Long) getting cheated out of her dreams of a lovely new home when the boyfriend predictably runs off with her hard-earned savings. It’s a familiar cinematic trope—trouble almost always arises whenever both the mother and her children all call the “man of the house” by his first name.

The event sets course on two critical film-long motifs, beginning with Shante pressured into a leadership role in her struggling mother’s household and quickly within her own life. The other significant theme is that of bad men and their toxic and fragile masculinity. In fact, it dominates the film at times to a fault, shaped as much by awful actions of men as Shante’s actions. (She’s even burned out of returns from her first tour by her shady manager.)

Shante’s doomed relationship with preying Cross (Mahershala Ali) teeters on illumination and trauma porn. The progression of the relationship is shown via a shocking and masterful edit of screaming Shante—during intercourse, in giving birth, into her drug-dealing abuser dragging her across the floor by her hair.

Swaths of the film lack depth, like many biopics that rush through proceedings in an effort to cram in as many real events as possible. But in one stunning scene, Adams channels Shante’s palpable exasperation while in the bath. After a tense conversation with Cross’ more delicate side, she submerges herself, hair and all. For Black people watching the film and those familiar, there’s an innate understanding of that pain.

The visceral Roxanne, Roxanne is a serviceable and necessary film carried by strong performances from Adams, Long, and Ali. It adds a significant story to hip-hop’s ongoing epochal tale, usually neglectful in recalling the import of women’s influence. Regularly shunted as eye-candy or novelty, the story of chart-topping women within hip-hop begins chiefly with Shante’s account as its first superstar “femcee.” Unquestionably, it should be remembered that she was simply one of its best, period.

Still not sure what to watch on Netflix? Here are our guides for the absolute best movies on Netflix, must-see Netflix original series and movies, and the comedy specials guaranteed to make you laugh.