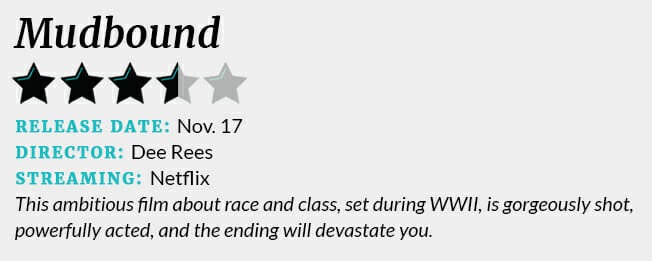

Mudbound is a movie caught in between two worlds. Streaming on Netflix, it’s the kind of digital release usually given to films which get great reviews but garner little attention, the very type of indie that Netflix has been building an arsenal of. It also wants to be an Oscar contender, and indeed has all the hallmarks of a fall prestige picture. Maybe this struggle is why the movie feels lacking in some essential way, despite also doing so many things so well.

Mudbound is the third feature film from director Dee Rees, who previously made 2011’s Pariah (also streaming on Netflix) and the HBO original movie, Bessie. As a swing to get the acknowledgment she deserves, it’s a big one. Adapted by Rees and co-writer Virgil Williams from Hillary Jordan’s novel, Mudbound traces the stories of two families during World War II, one white, one black. They intersect when the McAllan clan buys the farm the Jackson family has worked on as sharecroppers for years. Each family has sons who go off to war, and each faces economic hardship and personal strife back at home.

Period piece? Check. Social themes which still resonate today? Check. Horribly depressing moments of hardship followed by inspirational moments of triumph? You bet.

We’re still in the early stages of this year’s awards season, and another #OscarsSoWhite is not out of the question. Other than Jordan Peele’s horror juggernaut Get Out, Mudbound may have the best shot at preventing that. But it compares most closely to last year’s failed Oscar hopeful, The Birth of a Nation, in that it’s essentially conventional awards bait, despite telling a Black American story which, conventionally told or not, still deserves to be heard.

What may help Mudbound rise above comparisons is that Rees is also telling an inherently white American story. Every movie about systemic racism is as much about white Americans as any other group and the ways in which they’ve benefited from institutional prejudice. Mudbound brings an additional layer of nuance to the conversation.

The McAllan family members are inept at farming, and shortly after purchasing the land, realize as much. Their social station quickly begins to fall, yet they retain their standing over the Jacksons simply because of their race and the benefits it affords them. A Black sharecropper with experience was still lower in the societal hierarchy than a white farm owner with none in the 1940s.

As Ta-Nehisi Coates recently pointed out, part of the reason racism has flourished so long in this country is that even poor white Americans have bought into the delusion that their skin color automatically makes them higher class than Black Americans, regardless of whether they are in the same economic bracket. Mudbound is a cinematic treatise on this idea, embodied in the hubris and callousness of the McAllan family.

The chief architect of the McAllan’s ruin is Henry (Jason Clarke), a seemingly benevolent but overly prideful man who takes his wife, Laura (Carrie Mulligan) from their comfortable home in Memphis, Tennessee, out to rural Mississippi to fulfill his dream of farm life. Henry is quickly swindled out of a house and his decisions get worse from there. Clarke’s performance in the role is restrained, but he does a fine job of playing Henry as the kind of “good” white person who somehow stays ambivalent at every turn to the racism surrounding him.

The final major character in the McAllan family is WWII vet Jamie, sharply played by Garrett Hedlund. Hedlund is an undeniably captivating screen presence, though his all-American man persona has worked both for (Inside Llewyn Davis) and against him (On the Road). With Mudbound, he finds the perfect balance of masculine bravado and sensitivity. A romantic charmer turned into a compulsive drinker with PTSD by his experiences in the war, Jamie gives Hedlund the right amount of scenery to chew. It helps that he’s a supporting player, and the entire narrative doesn’t rest on his shoulders.

He’s the most woke white character in the movie, which by default makes him the most likable. Hedlund is giving a showy performance here, but he never fully eclipses Rees’ vision, managing to reign in his tendency to go big when he needs to.

Then there’s the Jacksons. In her first major acting role, Mary J. Blige easily commands the screen as Florence. It’s the kind of turn from a musician that you always expect, given what natural performers most singers are anyway, but Blige still manages to exceed those expectations. The film’s real revelation, however, comes from the least known member of the ensemble. As Florence’s husband, Hap, character actor Rob Morgan (Stranger Things, Daredevil, the upcoming Godless–-basically everything on Netflix) is nothing short of a star. The pain Morgan carries in his face and voice conveys a lifetime of disappointments and failures in a system that’s designed to keep working men like Hap down.

But if there’s an actor to place a bet on in Mudbound as an Oscar finalist, it’s Jason Mitchell (Straight Outta Compton). The other half of the film’s WWII brotherhood, Mitchell’s Ronsel Jackson has the best arc of the entire movie, and not just by a little bit. After serving in the war, he returns home to a country that asks him to use a different entrance anytime he goes somewhere. As he bonds with Jamie over war stories, it’s evident to both of these men that the tragedy of the war was actually preferable to Ronsel over the tragedy that is the life of a Black man in America. At least in Europe, he was seen as human. That it took something as awful as WWII to make Ronsel realize this might just be the greatest tragedy of all.

All these fine actors elevate what is occasionally a melodramatic and rote movie. This is a film where the chief antagonist is a racist old man known simply as “Pappy” (Jonathan Banks, who brings levels to his role that a lesser performer could not). The score, from frequent Rees collaborator Tamar-kali, is intermittently beautiful and effective, but then it swells, over-emoting and draining the subtlety out of otherwise well-constructed scenes. The film also features frequent voiceovers, most likely meant to be novelistic, invoking filmmakers like Billy Wilder, Ingmar Bergman, Terrence Malick, and Spike Lee. It’s hard to shake the feeling that you could take it all out and the movie would be just as good.

Despite seeing it on the big screen, a way in which most Americans aren’t likely to enjoy the film, I just couldn’t shake the feeling that I was watching a Netflix movie. Mudbound was acquired by Netflix, not financed by the company. Although it’s not a gorgeous-looking film, Rees squeezes a lot out of a modest budget. Nevertheless, when that red-and-white logo appeared on the screen followed by that “chu-chung” noise, my enjoyment was subconsciously tempered.

You should still give Mudbound a stream. The film has one of the most disturbing climaxes I’ve seen in any movie this year, one which will make any person with a conscience tremble in their seat. It’s not unusual for this type of film to include a scene of violence or evil that is truly harrowing. What stunned me, however, was what followed: When Mitchell’s character becomes the centerpiece of Mudbound’s finale, it’s devastating.

It’s worth watching Mudbound for that ending alone, but also for the potential the film signifies for Netflix and for the industry at large. It’s impossible to deny that Hollywood is better for taking a chance on filmmakers like Dee Rees and stories like this.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xucHiOAa8Rs

Still not sure what to watch on Netflix? Here are our guides for the absolute best movies on Netflix, must-see Netflix original series and movies, and the comedy specials guaranteed to make you laugh.