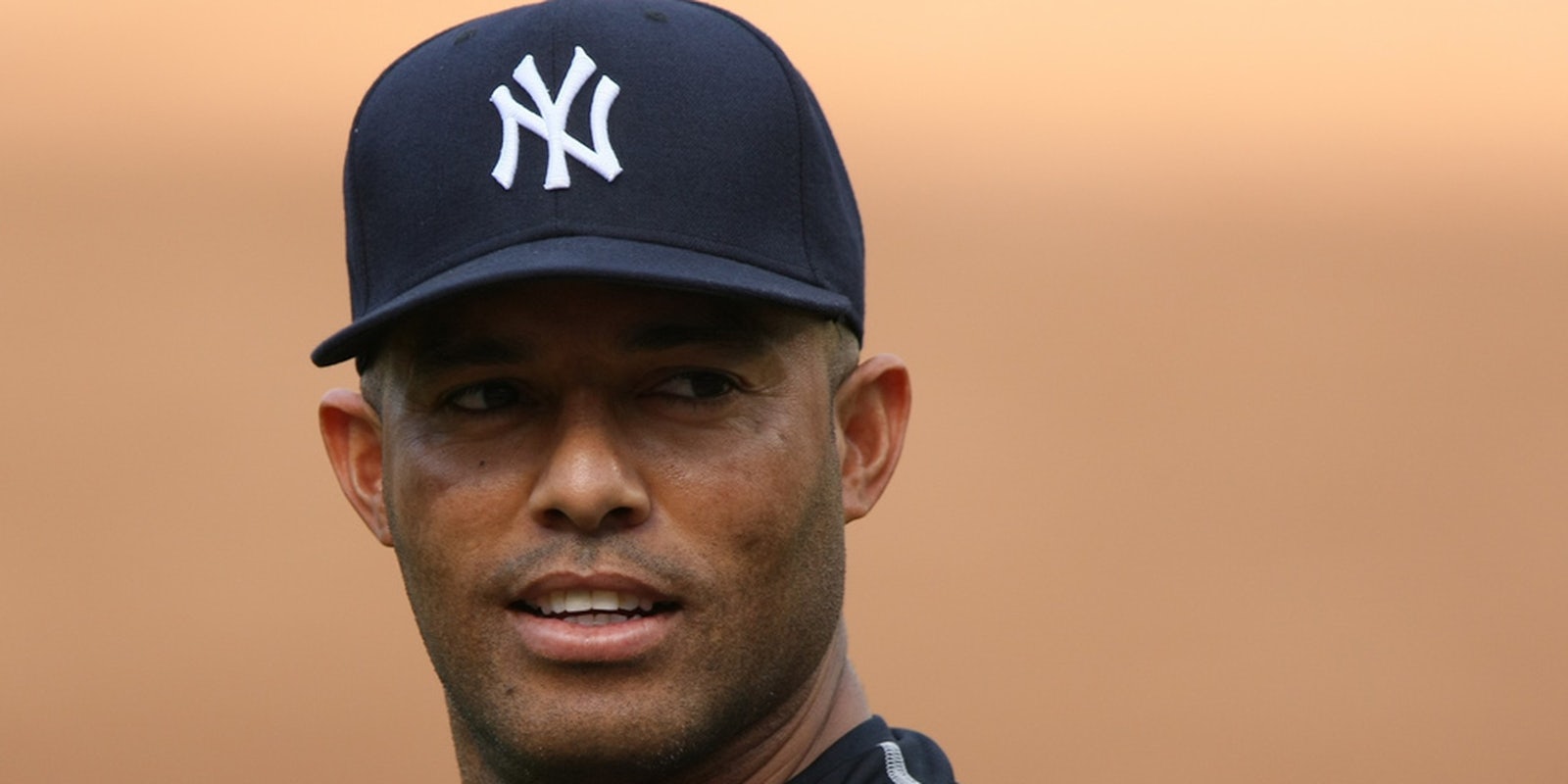

On Thursday night, in the eighth inning of an otherwise unimportant game for the New York Yankees, 43-year old closer Mariano Rivera jogged out to the mound for the last time. Rivera was to face an opposing lineup that already understood, at least statistically, that they were doomed: In his 19 years with the Yankees, Rivera had racked up more than 650 saves (the next closest active player has about half that). In the minutes that followed, Rivera retired four batters in a row. With one out left in the ninth inning, manager and one-time catcher Joe Girardi pulled Rivera from the mound. It was not because he couldn’t get the last out; indeed, he almost always did. But for the man who had taken the ball from the Yankees nearly two decades ago and gone on to become the greatest closer that has ever played the game, it was time to hand it back.

Nearly every major outlet, from the Atlantic to Al Jazeera, either circulated the video of Rivera’s last game or published an account of it. Certainly, that’s a rare thing for a retiring pitcher on the most hated team in baseball. But, of course, Mariano Rivera is not your average above-average Yankee, nor your average dominating pitcher. As ESPN wrote, “you did not have to be a fan of the Yankees to appreciate Rivera. You merely had to be a fan of greatness.”

For those who grew up watching Rivera, an era of baseball ended when he walked off the mound.

My mother is from Boston and so, if you have let yourself get caught up in the heartbreaking business of East Coast baseball, you know that I never was a Yankees fan and that I never will be a Yankees fan. You understand too how unfortunate it is that I lived most of my childhood during one of the Yankees’ most dominating periods in baseball history. In the decade begining with the 1996 season, they won 10 division titles, six pennants and four championships. Though I was a White Sox fan in those years, I would come to cheer for the Red Sox, the Indians, the Braves, and anyone else who became the Yankees nemesis of the moment. If asked my favorite team, I always responded: “Whatever team is playing the Yankees.” This decade-long streak began shortly after Rivera joined the club.

I’ve come to think that baseball in the ’90s, before the steroids scandal broke, gave kids what comic books had in prior generations. It was a place of heroes and villans, where the Yankees were the Evil Empire to everyone who wasn’t from New York. Growing up in this period of the sport’s history, we kids inevitably began to assemble a sort of cosmology of minor baseball gods: There was Ken Griffey Jr. with that perfect swing; there was David Ortiz who seemed to hit only home runs in October (arguably, he would later give this crown to Pablo Sandoval); there was reliable Cal Ripken Jr. who never missed a game; and of course, there was loyal Frank Thomas, the Dan Marino of baseball, who stuck with his losing team despite his unimaginable talent. But maybe most of all, there was Mariano Rivera, the man who, for 19 years, shortened games against the Yankees to eight innings.

Truly, this is no exaggeration. In the 914 times the Yankees have handed Rivera the ball with a lead, he has let them down on only 46 occasions. In the 68 games where Rivera was given a lead in the postseason, he blew it only four times. Christy Mathewson, the New York Giants player considered perhaps the best pitcher of the deadball era, once wrote that, “nearly every pitcher in the Big Leagues has some temperamental or mechanical flaw which he is constantly trying to hide, and which opposing batters are always endeavoring to uncover.” It is entirely possible that Rivera had no such flaw.

The position of closer is unique in American sports. Unlike football or basketball, one cannot run out the clock towards the end of a game. Baseball is over exactly when the last out is called. The closer is the last line of defense for a team clinging to its lead in the final outs. The closer is the man to beat. And Rivera was the best. This is why every little league kid, when acting out their baseball fantasies in the backyard after dinner, invariable dreams up the following scenario: It’s two outs in bottom of the ninth, bases are loaded and their team is down by one. Even if the rival pitcher is unnamed in this plate-pounding monologue, it is always understood to be Rivera. Because to be a hero, you must topple the god of the ninth inning.

In his backyard, the kid always hits a grand slam off Rivera and rounds the bases, jumping up in down in victory with his imaginary team.

Though we might not have realized it then, it was, of course, just a fantasy. Most of us never got a real shot at toppling Rivera. Anyway, even if we had made it all the way to the majors and faced the game’s greatest closer, we likely wouldn’t have bested him. Almost no one did.

I have no idea the mythical pitcher young kids five years from now will face in their backyards. But it won’t be Rivera. It is possible, in fact, that no one writing about Rivera will live to see a worthy replacement. As ESPN pointed out, it would be statistically difficult for anyone to topple his records in the next two decades. Perhaps the unease of that thought is akin to how comic book fans from generations ago felt in 1992 when Superman died.

Asked about the decision to kill Superman years later, the storyline creator said, “the world was taking Superman for granted.”

Photo by Keith Allison/Flickr