The Daily Dot is observing Emo Week with a nostalgic trip down the oft-derided genre’s most influential, infamous alleys. Cue up your favorite CD-R and hug it out with us.

“Do you remember Makeoutclub?”

This is a question I asked quite a few friends and acquaintances this summer. The majority didn’t, or they knew the name but never ventured in. Those who did all had variations of the same reaction: The eyes softened a bit, a “wow” or “holy shit” was uttered. A long-gone memory or old self remembered.

“Is that still around?”

Named after a song by D.C. band Unrest, Makeoutclub was borne of a special time and place. In the year 2000, the party was still small. The internet wasn’t yet a series of rabbit holes. Our pages loaded slowly and we got a thrill out of pretending to be someone else on AOL Messenger. But in one awkward corner, a website existed where kids were celebrating exactly who they were.

When the site debuted in July 2000, the term “social network” wasn’t clearly defined or branded. MOC was a place where suburban teens could go to talk about punk, hardcore, and emo bands, and shape an identity. It was a platform for trading mixtapes and promoting bands. It allowed users to meet people in other cities and spend time in other music scenes; an exchange program of sorts; a makeshift, early Airbnb. And a lot of people were using it to hook up.

In 1999, when a beta version was launched, founder Gibby Miller was living in Boston and attending the Massachusetts College of Art. Then, the internet “felt very much like a private place,” he says, though the late ‘90s tech bubble had opened up more opportunities for people to connect. A Philadelphia label called Track Star Records had a section on its website called “Sexy Scenesters,” which accepted user-submitted photos and would post them with captions making fun of said scenesters. Miller’s submission got “torn apart,” but it gave him an idea: People were getting to know each other from this shared interest in music and mocking themselves. What if there was a place where these people could network?

“And I remember a friend of mine was like, ‘Network? That sounds so cheesy,’” Miller recalls from Los Angeles, where he now resides. “I remember thinking, that’s a bad word. I won’t use that word.”

Miller grew up posting to bulletin boards in the dial-up days, and says that influenced MOC’s creation. “Back then the internet still felt very underground, very secret, and frankly, it didn’t do much,” he says. “I was really interested in pushing the potential of what could be done, developing something that nobody had done or seen before, and innovate on products that could change the way we thought about the internet and about ourselves.”

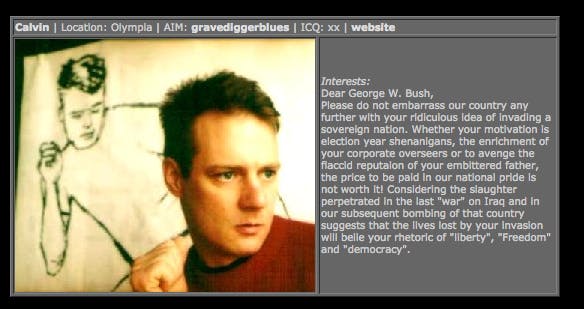

At age 22, Miller launched the site. There were a few other fledgling social sites at the time, like Six Degrees, but those mainly worried about how many people you knew that knew each other. MOC was focused on an emerging youth subculture and aligned music scenes. In the early days, your profile was a small grey box to fill with your interests, AIM or ICQ handle (remember that?), and location. There weren’t likes or reactions or shares. You were known by your username—handles like cuddlemonster, nintendork, bloodxbutterflies, and countless names that began and ended with X—and usually a low-res, badly lit, angled profile pic.

In combing through the message boards, many of which still live on the Internet Archive, there’s an absence of the slang that makes up online communication in 2016, but there were proto memes, as well as references to Livejournal and links to Rotten.com. People self- and scene-identified: vegan, scenester, straight edge, emo, goth, poser, elitist. People shrugged off those same labels.

Glory days

Mark T. Manning joined Makeoutclub in the early aughts, though he can’t remember the exact year. “It was a completely novel way to communicate with each other,” he says. He went on to become an admin on the message boards, the site’s most popular feature, where he says a “core group” ruled the virtual streets.

Even though the party was still small, there was a hierarchy.

“There was an initiation,” he says. “If you hung out long enough and navigated the minefield and shit-talk, you were kind of accepted as part of the group. And if you didn’t fuck up.”

Though MOC still exists, the golden era was 2000-2003, when the message board was its town hall. Drama and catfights became part of the culture. There were cliques and popular kids, just like in music scenes. Noobs were judged.

“People were looking for someone to kind of fuck with,” Manning says. He relates that he and Miller were often the good cop/bad cop on the boards—with Miller as the former.

“There wasn’t a delete button or an edit button [for users], and that was by design,” Miller explains. That added to some of the chaos of the message boards, as users unloaded posts they couldn’t take back in the sober light of day. Still, the boards became a source of entertainment, before *grabs popcorn* became shorthand for gleefully watching internet fights, as well as a confessional.

They also became a historical document of the early aughts. There are quite a few threads about the 2004 reelection of George W. Bush, and the 2003 invasion of Iraq. Miller remembers opening Makeoutclub the morning of Sept. 11, 2001, and seeing pages of people sharing their thoughts.

“It was an outpouring,” he says. “Now we have a million ways. … You can tell someone how you’re feeling by sending them a fucking emoji now, but it became people’s almost personal blog in certain times.”

The site was divided into “girls” and “boys,” and while it was not designed to facilitate dating, hooking up (and traveling to hook up) became a big part of the experience. “It was new, and there was still a bit of naivete about meeting strangers on the internet,” Manning says. “But we were just kids, cobbling up enough money to meet these people or hook up.”

Gracie Brown got on the site when she was 16. “It was a weird period,” she says. “I was coming out of my nerdy, ugly high school phase, and starting to date boys and had my own identity… [it] was a constant place to go where people were always there. And making so many friends there was really cool.”

Brown, who’s now a moderator on the site, says in 2008 she threw a party in Brooklyn, New York, and people from MOC flew in from around the country to attend. She’s getting married next year, and 20 percent of her guest list is people she knows from MOC.

For all the lust, Manning says he wouldn’t necessarily call MOC a “sex-positive place.” Women were objectified; photos were “rated” and nudes circulated. (Miller claims the site had more female users or it was “50-50.”) Brown says she didn’t have any run-ins with creeps: “There weren’t a lot of people who nobody knew.”

Eventually they developed a password-protected gallery where nudes could be seen—the “MOC Lock,” as Brown remembers—and it included men’s and women’s nudes. It “created a submerged world of commenting and relationships based on who did and didn’t have access,” Miller concurs. There were also “crush lists” where you could “crush” someone but they’d only be notified if they also crushed you—a proto-Tinder.

Miller says he used it for dating too, but is adamant it was more than that.

“We were bridging the distance between these kids that could have never have known each other otherwise,” he says. “That, to me, was the power of it. I thought back to growing up in Missouri and sitting in my bedroom and listening to college radio and taping music off of the radio, and my big social network was, I can walk down Delmar [Blvd] and hang out and smoke cigarettes in front of Vintage Vinyl and try to work up the courage to talk to people and meet more kids.”

Plugged in, washed out

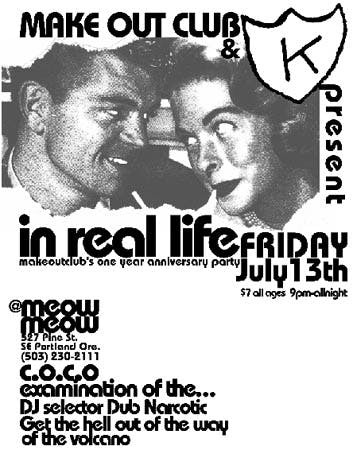

Facebook, Twitter, SoundCloud, Bandcamp, and YouTube facilitate booking and exposure for bands, but in 2000 promoters advertised and booked shows on MOC. There were mixtape circles and IRL meetups and shows in different cities. Miller says there were “dozens if not hundreds of bands that formed on MOC.”

Calvin Johnson of Beat Happening and K Records had a profile, which addressed then-president Bush.

It was a time when music criticism was shifting, not necessarily in terms of gender equality but medium. Male-dominated early aughts sites like Buddyhead and Pitchfork became destinations for obsessive fans looking for gossip and new music. MOC was a frequent target for Buddyhead: In 2001, founder Travis Keller branded the site “online ass-shopping for geeky virgins with bad taste in music.”

I can’t remember how I found out about MOC. (I had a minor panic attack when I tried to remember how I heard about things before social media.) But I got on the site to discover new music. I was in my last years of college and consumed with finding punk and experimental tunes outside the isolating confines of suburban South Florida. I was traveling to see gigs in different cities and states; getting to know myself and figure out my scene. I started a zine with friends so I could write about and interview my favorite bands, and tell people about my scene.

Here was a site where people were talking about the same obscure bands, and teaching me about new ones. It was a different kind of history lesson. The anecdotes I got from people I solicited this summer were all music-related: getting catfished by a friend who said she was dating Conor Oberst, meeting a guy from the site at a gas station a county over to go see the Starting Line. There was a naivete that seems intangible now.

In his 2003 book Nothing Feels Good: Punk Rock, Teenagers, and Emo, author Andy Greenwald attempted to deconstruct MOC’s allure: “Makeoutclub is a safe haven and reinvents itself nightly. There are no limitations of temporality, no outdated battles over cred, because the site itself is a constantly mutable battlefield.” Miller credits Greenwald’s 2001 Spin article on Makeoutclub for bringing a flood of curious users to the site, and adds that MOC “was present for both eras of emo: the late ‘90s and early aughts ‘real’ emo and screamo period when it was defined by bands like Heroin and Saetia and Rites of Spring.”

When younger kids started joining the site, they identified more with the “Myspace-era Hot Topic version of emo that had become more about a sort of mall-punk image and less—I feel—about the music.”

There were exoduses: A core group of early users left for now-defunct spinoff site Lipstick and Cigarettes.There was a renaissance on MOC between 2007-2009, when the site debuted new features like private photo galleries, badges, and blogs. The rise of Facebook siphoned some of the traffic.

“It was definitely a time and place,” Miller says. “And I think over the years, Makeoutclub didn’t move away from that. Maybe one of our big faults was that we kept trying to recapture that magic. The magic is only there if you feel it or know it or remember it.”

The leaving song

In a testament to the site’s enduring nostalgia, the 2016 version of MOC now largely exists as a place where older members come to talk about MOC. A relaunch happened in 2014, and Miller says there are roughly 200,000 users now, but it’s harder to quantify how many users were online in 2000, when the party was smaller and real names weren’t required.

The feeling of being part of something new, exciting, and secret is hard to come by now. At this year’s VidCon, there were at least three different platforms where teens could livestream themselves. YouTube and Snapchat are confessionals. Twitter and Reddit are message boards. Posting your every thought to Facebook is accepted. If you’re lonely or bored or heartbroken, the voids you can shout into are endless.

Miller, who in addition to MOC works in mobile advertising and runs the label Dais Records, thinks Facebook’s success in getting people to stay for so long lies partially in its approach to privacy. Myspace and Friendster were open networks, and Facebook anticipated that users would want more ownership. This year, MOC went 100 percent private.

“When you log into Facebook, you are seeing your curated social experience,” Miller says. “Technically and socially, Facebook simplified access to the social networking ‘product’ and commoditized it—normalized it. … Facebook encapsulated the experience so it could all be done within their walls. They, in a sense, ate the internet.”

Miller sees that the party might be ending soon. But he’s not ready to turn off the lights just yet.

“I would never say the site’s dead, but it enjoyed its time,” Miller says. “It’s definitely changed, and I’m having a hard time coming to terms with unplugging it. It’s not that I’m unable to face reality, but it’s tough. It’s kind of my baby.”