Korea’s K-pop could be a twin of American mainstream media. Think of it like the Parent Trap: The two share very similar features—catchy music, visual appeal, and strong fanbases—but maintain their own cultural identities.

But just like in the Parent Trap, they inevitably meet.

Being a fast-growing global presence, it only makes sense that K-pop would learn and borrow from one of the most successful music industries in the world. But in the quest for a hard-hitting single, all too often artists become guilty of cultural appropriation—a nagging issue plaguing the genre’s evolution.

One—if not the—main avenue for cultural appropriation in the industry is through K-pop’s use of concepts, or themes, in music. Concepts act as a major differentiation between American pop artists and Korean pop artists.

In K-pop, groups often adopt a concept or theme when promoting their singles (known more regionally as “title tracks”). A concept ranges anywhere from broad themes like love, youth, or partying, to specific ideas such as secret agents. Regardless of the choice, the music, lyrics, choreography, and clothes all contribute to convey the idea.

When another culture becomes the concept, controversy ensues.

Ph.D candidate Stephanie Choi is a native Korean studying ethnomusicology at the University of California, Santa Barbara. While she focuses her research on K-pop, she also finds time to enjoy the music, her favorite group being BTS, a seven-member, hip-hop-inspired group.

When defining cultural appropriation, Choi called it “[taking] an element of another culture for your own use or advantage.” That entails the economic profits and reputation, but leaves the responsibility of conveying that culture and the meanings behind it, she said. Essentially, it’s like a one-and-done kind of deal where the artist or company gets to choose how to enterprise that identity and leave once it’s served its purpose.

“The people of the culture they use become voiceless,” Choi told the Daily Dot. “They lost their voice to properly convey the culture, meaning, or values of their own culture.”

In Korea and among K-pop fans, the term K-pop really refers to idol music, or the musicians who make up the immediate mainstream. If we’re talking “Korean popular music,” there’s more to it than just pop, Choi said. It includes K-hip-hop, K-indie, K-rock, and more. K-hip-hop especially has a very prominent position next to idol music and is more or less just as guilty of appropriating culture—especially black culture.

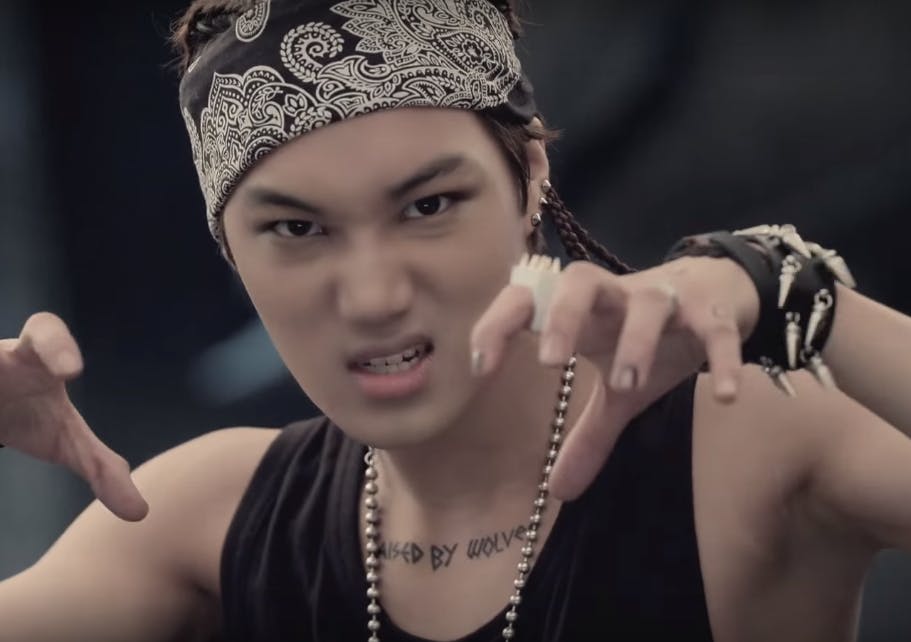

Sometimes the offenses come in small doses, such as one member of the group sporting cornrows and bandanas. Just like in any romantic relationship, little things matter: It’s a subtle means of perpetuating stereotypes and taking from an appearance that belongs to someone else.

Sometimes the cases are much more blatant, and in those instances, fans respond—especially those who feel directly offended.

An older, but classic example of brazen cultural appropriation is girl group T-ara’s 2010 release of “YaYaYa.” The title track offends Native American culture on a multitude of levels. For one, the lyrics feature very little words (in English or Korean) in favor of chants and yells. Stereotypical gestures make up the choreography, including T-ara’s members bobbing their hands over their mouths and prancing around an attractive male tied to a pole. Feather headbands, face paint, beaded jewelry, teepees, tribal patterns—it’s all there.

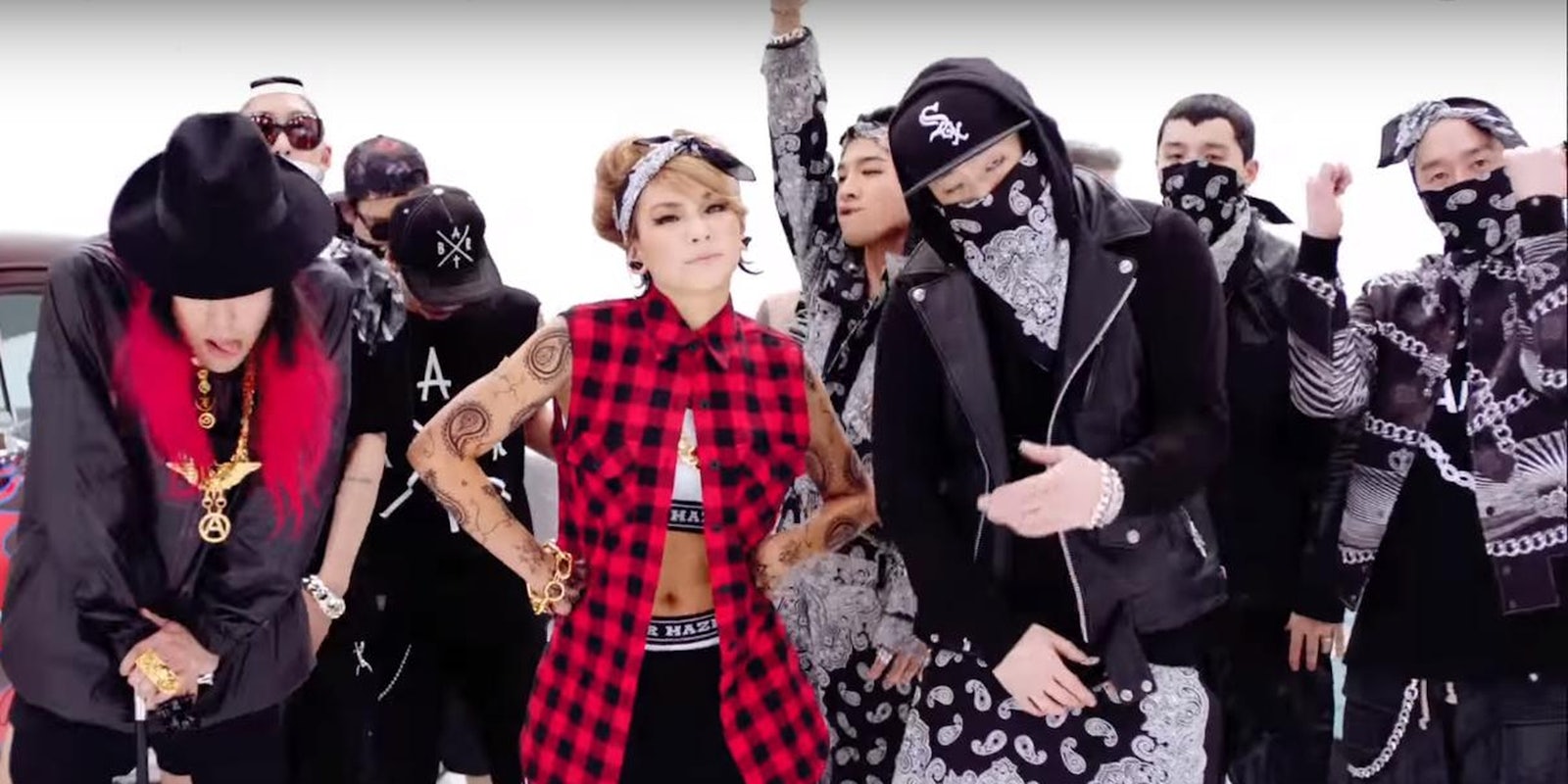

CL, the leader of YG Entertainment’s girl group 2NE1 is often under fire for the music videos she releases. CL’s most recent solo release, “Hello Bitches,” features the New Zealand-based ReQuest Dance Crew. You might recognize the group for their dancing in Justin Bieber’s Purpose: The Movement videos for “Sorry” and “What Do You Mean?”

None of the girls from ReQuest who appeared in CL’s video are black, but that didn’t preclude the tanned skin, cornrows, and abundance of twerking.

In the past, CL has also struggled with cultural appropriation claims. In her 2013 single “Baddest Female,” she presents herself wearing grills and gold chains. In 2014, the backlash came raining down after her solo track “MTBD” (short for “Mental Breakdown”) was released on 2NE1’s Crush album. The track sampled a boy reciting verses from the Qur’an, which Muslims found very offensive, especially considering music is a point of contention in the religion.

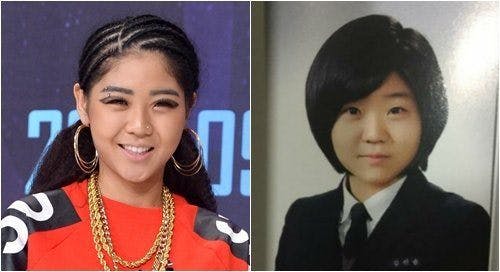

Choi’s dual definition of K-pop extends to artists outside the idol world as well, which includes rapper Truedy. It’s more fitting to call her a K-hip-hop artist as opposed to a K-pop idol, but it doesn’t discount the fact that the musician is guilty of appropriation. Last year the star performed on a survival-style reality show called Unpretty Rapstar 2 that featured female rappers.

Truedy’s flow and aesthetic led people to believe she was of both Korean and black descent. With some research, fans discovered that this wasn’t the case, inciting a fair amount of rage. K-pop news outlet Omona They Didn’t! called her “Korea’s own Rachel Dolezal.”

Why does this keep happening? The answer is rooted in economics. There’s millions to be made riding the coattails of American pop culture. It only makes sense that K-pop would look to it for inspiration.

“Most of the stereotypical images that [K-pop] portrays comes from American media,” Choi said. “It’s not something they experience from their actual lives, they’re just imitating what they see.”

Without understanding a culture and its meanings, we get caught in an endless cycle of appropriation. K-pop is considered the Hallyu wave—it represents Korea worldwide—but by no means does it accurately depict its day-to-day culture. Yet it’s not uncommon for people to think it’s normal for Korean men to wear makeup the way male idols do, Choi said.

“People learn about the entire nation [of Korea] through K-pop,” she explained. “It’s the same with Koreans too, they learn about black people through American mass media.”

The money may be in the trends, but it has to flow from somewhere. Ultimately the source lies deep within the fans’ pockets—more specifically, Korean fans’ pockets. Choi has noticed that the average age of Korean fans can be much higher than that of American fans.

While K-pop is gaining traction in America, the fact that its stateside fanbase is primarily teenage girls can’t compete with the young adults and professionals who make up a substantial demographic in the Korean fandom. They simply have more disposable income to invest in the genre.

When it comes to international fans, it’s not even American fans—or Western fans in general—that make up the majority, Choi said. It’s Japanese fans. So it makes sense for K-pop to cater to that market, which is why we often see Japanese releases. Groups like Shinee are affiliated with Avex Group, a popular Japanese entertainment company, and regularly release title tracks geared for Japanese fans. There’s also a common tendency to avoid any kind of controversy with its Japanese counterparts, Choi said. As a result, any Japanese cultural appropriation in K-pop is carefully vetted.

It’s also important to know who’s responsible for the concepts, lyrics, and clothing. When it comes to cultural appropriation, the entertainment companies are the ones to blame, according to Jennifer Gabriel, author of Korean culture blog Western Girl Eastern Boy. Gabriel lives in Seoul, but hails from Austin, Texas. She brands herself as “a legal and marketing consultant in Seoul by day and Korean culture blogger by night.” On her blog, she often writes about her life in Seoul as a black woman and happenings on the K-hip-hop scene.

“Ideally, we would get less cultural appropriation and more creative expression,” she added.

Gabriel thinks the K-pop industry is tightly scripted. “We often blame idols for cultural appropriation in K-pop, but it’s not the idols that are producing their songs, styling their outfits, and coming up with their choreography,” she told the Daily Dot in an email. “They’re just the final products, products made by an entire agency.”

This presents the problem of idols being unable to take full responsibility for their actions, whether right or wrong, Gabriel said. And if they could take responsibility, it would give them the freedom to express themselves on a more genuine, legitimate level, Gabriel argued. “Ideally, we would get less cultural appropriation and more creative expression,” she added.

Until then, spicing up the diversity would probably help, Gabriel said. “You don’t see more diversity in K-pop, be it the people producing idols or debuting as idols,” she said.

But if that’s not enough to convince you, perhaps it’s time for a condensed history lesson. Choi noted how the history of Korea vastly differs from the history of America, for example. Unlike the Americans, it was Korea that was conquered by others.

“Korea was colonized by Japan, and they are still suffering from the colonial history,” she said. Out of fear and hardship, a prevailing sense of xenophobia blanketed the public. “Very often, xenophobia is [used] to defend ourselves against these foreigners,” Choi said.

Gabriel also weighed in, citing the Korean War and how it gave generations a bad impression of foreign soldiers. “That’s why there is this continuous sense of being on the outside looking in, no matter where you are from,” she said. “We are all foreigners.”

The biggest hurdle to clear is shared by Korean fans and entertainment companies—they don’t appear to care about fallout from cultural appropriation.

“I don’t think the industry is affected by anything,” Gabriel said. Whether the music offends certain minority groups or paints a negative image of them, it doesn’t matter so long as those groups aren’t from a main market group. “Why would companies care what a small minority think? They are not even aware of us,” she added.

Referencing the CL/Qur’an controversy, Choi pointed out that despite the international Muslim fan reaction, it took an official complaint from a Korean Muslim group to elicit any kind of response from YG Entertainment. “That shows how they really don’t care about international fans unfortunately,” Choi said.

But it’s on the fans too, according to Gabriel. “You have to realize that most K-pop fans do not care about cultural appropriation,” she said. “They do not acknowledge it. If they do, then they defend their idols or attack the victims of cultural appropriation and say we shouldn’t care.”

It’s easy to write off when you aren’t the subject of appropriation. “It’s never helpful and always harmful—at least to and for black communities and black people,” Gabriel said. “K-pop is consumed on a global basis now, and perpetuating negative stereotypes of black people does little to change the current undercurrent of racism in South Korea, even Seoul, and the rest of the world.”

Of course there are some cultural aspects to be shared. It’s not as though wearing basketball jerseys in a music video automatically makes it guilty of cultural appropriation. But there’s a very fine line, and if something is going to be borrowed, it’s crucial to have understanding and awareness. “It’s an ethical issue,” Choi noted. “You need to respect other cultures and you need to properly convey their cultural values.”

Screengrab via 2NE1/YouTube