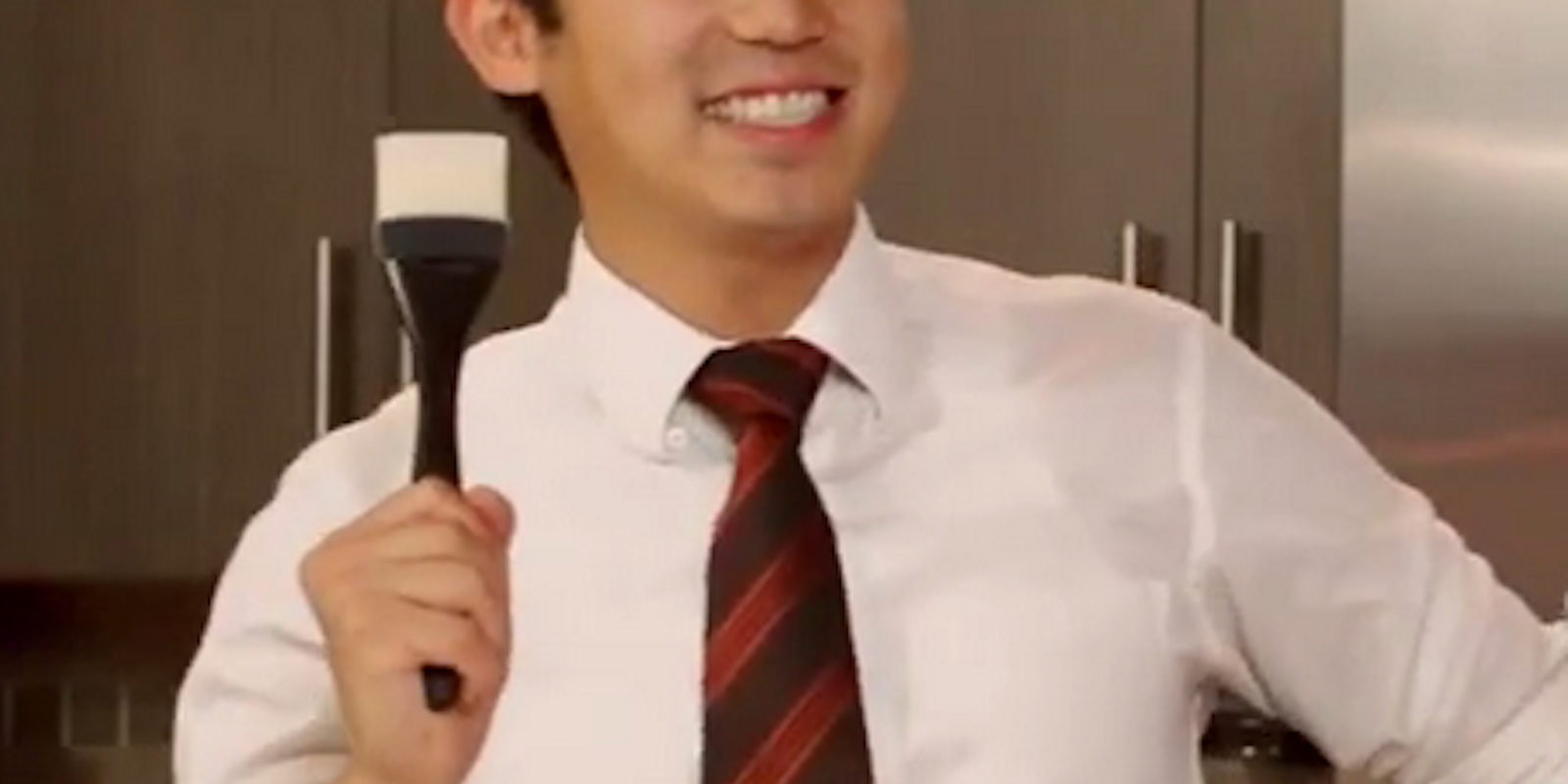

Part-time musician, full-time entertainer, Jimmy Wong holds a firm grasp on YouTube’s ever-contorting pulse. And if he’s not on your radar yet, it’s really only a matter of time before he will be.

At 24, Wong is the consummate summation of the type of individual born to make a splash on YouTube. He’s handsome and articulate, energetic and clever. When he speaks, he exhibits a worldly knowledge of who he is as a public personality: a well-known YouTube personality, sure, but hardly the brightest star on the small screen.

In fact, Wong doesn’t even have the most YouTube fans in his own family. At 174,564 subscribers, Wong falls 3,186,214 fans short of his brother Freddie’s tally.

But Jimmy Wong can do one thing his brother can’t: Jimmy Wong can sing. He’s trained as an actor—he majored in theater and drama at Middlebury College in Vermont—but Wong’s greatest YouTube success has come through his music-related posts. It was because of his politically charged “Ching Chong! Asians in the Library”—a direct response to UCLA student Alexandra Wallace’s racist rant in the winter of 2011—that he was able to first crossover into the mainstream, where he appeared on NPR’s “All Things Considered.”

Since then, Wong has used his YouTube channel as a major marketing tool for his musical endeavors, posting everything from original works and cover songs to guerrilla-style concert clips.

“I’ve found that it’s an easier way to reach people,” Wong told the Daily Dot. “Your material is permanently there. People can always go to it if they want to catch up with you as a musician and performer.

“I didn’t come to realize how effective it was at promoting myself as a musician—as a working musician. Things started to line up down the road in terms of companies coming to me for brand deals or people who would want to work with me on a collaboration, people who had seen my music on YouTube.”

The effort has yielded him offline work and a steady influx of brand deals that’s helped him stay afloat and able to keep a downtown Los Angeles apartment, but those perks don’t make up the greatest thrills in Wong’s professional day-to-day. Instead, the Seattle native relishes the fact that he holds every card in the creative deck. There’s no management team telling him what types of songs to write, no publicist telling him how he should frame his look.

“The sky’s the limit for me every time I sit down to write,” he said. “I have complete artistic freedom to put something out there. You can really try out what you want.

“YouTube has been a big trial of sorts; I’ve always mixed and matched my genres and did what interested me musically at the time, instead of having to be more formulaic. “

Another YouTube perk: promotion is practically involuntary.

“My subscribers did the talking,” he said. “I didn’t really have to put myself out there more than just posting to whatever social media I wanted to be a part of, which is very organic and good way to spread music around.”

Wong pointed to OK Go as a band that’s been able to crossover from YouTube into the mainstream. But he was quick to counter his own words, calling YouTube “a centralized hub for people to go if they want to see my music, and that makes it such a more personal experience.”

“What separates YouTubers from people on YouTube is that personal bond between a YouTuber and their audience. We’re actively reading comments and actively talking with our fans, which is something you don’t see with more mainstream bands.”

Lately, Wong’s found success attracting fans in new places. Like many of YouTube’s independent personalities, he’s noticed a change in the video community’s focus. What was once a massive launching point for DIY stars and viral video makers has since become a hybrid between the old structure and a new, glossier model—one more transfixed on premium content and network affiliates.

“I think that the entire community has noticed a change,” he said. “It’s partly due to YouTube expanding its programming and adding the premium channels, but it’s also just a general trend that’s happened over time.

“As YouTube grows, so do the number of creators and so do the number of people on the Internet. These things are increasing at an incredible rate. A lot of our audience subscribes to so many people. The more content that you put online, the harder it is for individuals to tune in to everything. It’s not a pledge of allegiance. It’s more that the people who watch our videos are being inundated with so much material right now. Some of it’s great, but a lot of YouTubers are left behind. That’s just how it is.”

Count Wong among the chosen few who won’t get left behind. He’s a master of the duck and swerve. He starred in John Dies at the End, which premiered at the Sundance Film Festival last winter. In March, he and his brother launched a gamer Web series called “VGHS (Video Game High School).”

Wong also maintains a steady release schedule on Feast of Fiction, a YouTube channel he launched with Ashley Adams in December. There, Wong and Adams gather each week to cook foods derived from fictional books and movies. The two have made everything from elder scrolls sweetrolls to SpongeBob Square Pants-inspired hamburgers. On Tuesday, the two crammed into the kitchen with the three guys from Sorted Food to make a Turkish Delight dish first found in the Chronicles of Narnia.

“You just have to adapt and work with it,” he said. “Things may not be as strong as they used to be, but that’s not a bad sign. Your audience still exists, you just need to find another way to get at them and get yourself noticed by those people.

“I wanted to put myself out there in a different spectrum, so I started a cooking show. There is some cross filtering, and there is some cross love between the people on my music channel and the people on my cooking show. It’s not killing off one channel to pursue another. If they’re subscribed to you as a person, they’ll probably like what it is you’re doing.

I’m looking towards a very long game, which is not to be around in February but to be someone that people know ten years from now.”

Photo via YouTube