“Art is long,” quips Arthur Miller in the new HBO documentary, Arthur Miller: Writer. “Life is short.”

Miller is probably as good a vessel for this message as anybody. His plays have continued to endure years after his death in 2005. But HBO’s documentary comes at an interesting moment to consider his legacy. While Miller’s work will always endure, the kind of figure Miller himself represents is out of place in our cultural landscape.

Writer bears some resemblance to titles such as Capturing the Friedmans, Life Itself, Listen to Me Marlon, Jim & Andy: The Great Beyond, and Sarah Polley’s bold Stories We Tell, in that it uses home movies and personal interviews to give the viewer an intimate, behind-the-scenes look into the subject’s life and perspective. The reason the film was granted this footage, along with excerpts from Miller’s journals and letters, was because it was directed by his daughter, filmmaker Rebecca Miller. This familial connection adds another layer to the movie too, one which is central Writer’s successes and failings.

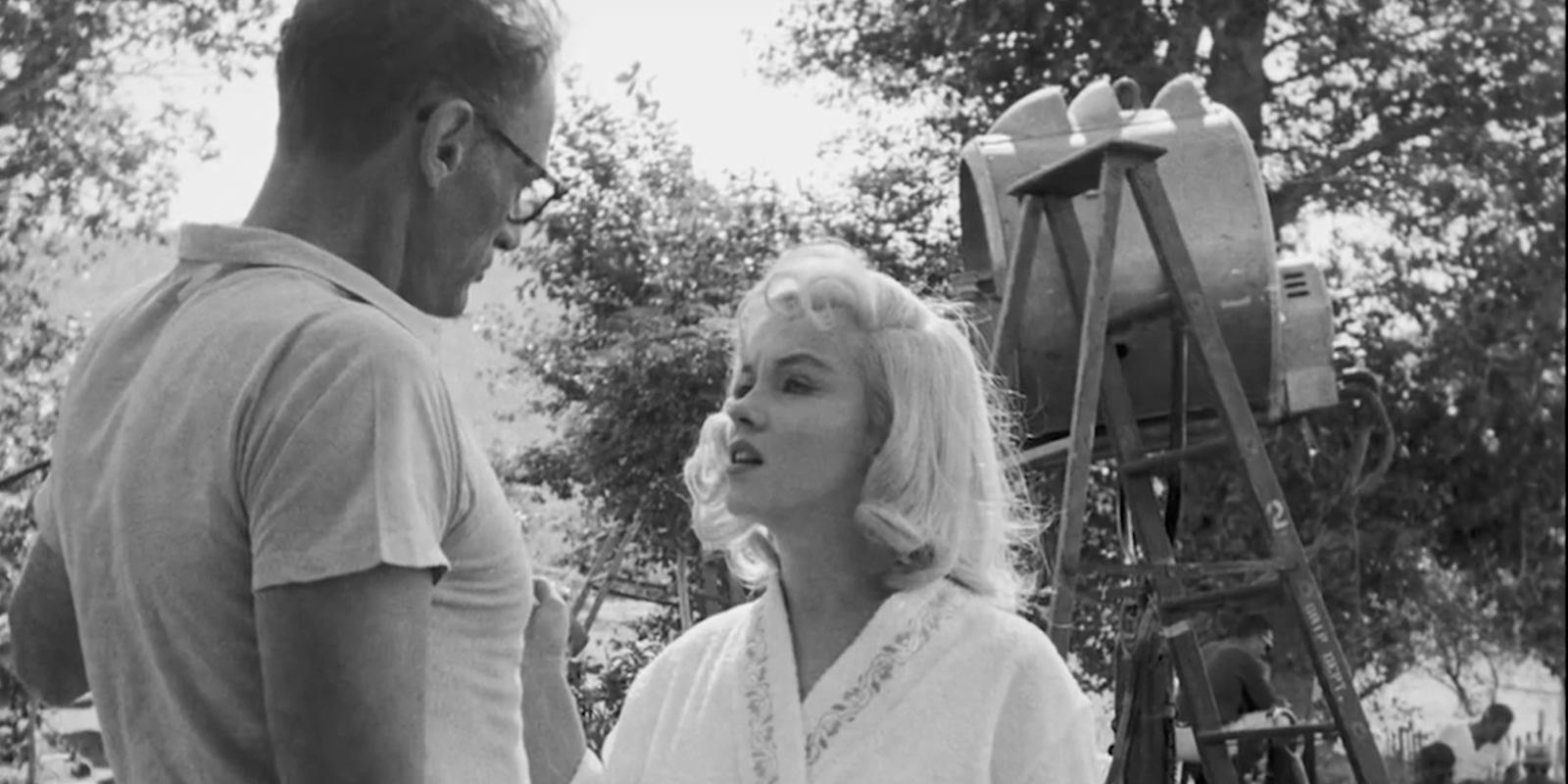

The film tracks Arthur’s entire life, from his humble upbringing in Brooklyn, New York, to his successes on Broadway to his marriage to Marilyn Monroe and beyond. For anyone interested in his career or the theater in general, the approach is perfectly serviceable, and Writer does a fine job giving you a general overview of his life. But it’s Rebecca’s footage of her father that makes Writer memorable.

“The parent is always a mythological figure,” Arthur tells his daughter in one of her interviews with him. Rebecca paints her father as more of an average old man. “I enjoyed being a father. I enjoyed, also, escaping being a father,” he tells her in another scene. One gets the sense though that by the time most of this video was taken, Arthur had settled into comfortable old age. It’s hard to reconcile this smiling, furniture-making old man with the giant of the American theater who once left his wife for the most glamorous movie star in the world. Rebecca knows this, and in the movie’s better moments, explores the disparity.

In 2018, Arthur’s plays, Death of a Salesman, The Crucible, All My Sons, A View from the Bridge, and more, continue to be performed around the world. At one point, amid footage of a Japanese production of Salesman, Arthur refers to this international success as “the happiest thing of my professional life.” Yet there’s something undeniably and intentionally American about most of Arthur’s consistently broken, typically masculine protagonists.

“I was more of a rebel than a revolutionary,” Arthur muses to his daughter. It’s easy to forget now how important a play like The Crucible was in holding up a mirror to the McCarthy era, and the film also does a good job covering his own battles with the House Un-American Activities Committee. However, it’s also easy not to dispute Arthur’s own analysis of himself. He all but embodies the straight, white, and male archetype that was a stand-in for American artists and intellectuals throughout most of the last century. Today his plays are merely rebellious.

The movie acknowledges this too, with Arthur talking about his difficulty to write material that connected with audiences in later years. “The art is to turn your back on what hasn’t worked, and go forward to what you think might well work… one day they’ll catch up to something or they won’t,” he says, discussing his critics.

The documentary also explores a few less highly publicized aspects of Arthur’s life, such as his Jewish heritage and the relationship he had with his son with Down syndrome, or lack thereof. Rebecca, unfortunately, doesn’t get to fully cover her father’s feelings on Daniel Miller, the child he was largely estranged from, though she claims she planned to talk more about this with him but he died before they could.

One person Daniel did supposedly have more of a relationship with was Inge Morath, his mother, and Arthur’s third wife. Morath, who was Rebecca’s mother too, was a German photographer who traveled around the world and lived a fascinating life. Someone should make a documentary about her too.

As almost a bonus, Writer is full of nuggets from Arthur which are simply and unsurprisingly insightful, coming from the mouth of one of the most acclaimed writers of the 20th century: “Pessimism is one defense I have against optimism,” “no play is finished,” and “the human being is a work of someone’s imagination… maybe God’s imagination,” were just a few that stand out.

Rebecca talks in Writer about how she intended to use the footage she collected to put together this documentary years ago. Maybe that’s why, for all the intimate material she does have here, Writer never feels as special as it could be. All these years later, Rebecca still hasn’t quite arrived at any revelations about that disparity between the personal and professional life which is ostensibly the movie’s central theme. The film reminded me of another recent documentary in that way, Joan Didion: The Center Will Not Hold, which was also directed by one of the subject’s family members, Griffin Dunne. Didion is still alive, so Dunne didn’t have to rely on the old footage Rebecca did to profile his aunt. The interviews in The Center Will Not Hold are more recent and less private than what we see in Writer, but the tenor of the films and conclusions they arrive at are essentially the same.

Public intellectuals like them are a dying breed, and movies about these kinds of literary titans remain as interesting as they are rote.

Still not sure what to watch on HBO? Here are the best movies on HBO, the best HBO documentaries, and what’s new on HBO Go this month.