Comedian Hari Kondabolu has been described as a political comedian, activist comedian, social justice comedian, and South Asian comedian. But as he seeks to clarify on his new album, out Friday on Kill Rock Stars, he is first and foremost mainstream.

“I don’t like being niched as a thing,” he explains in a standup bit. “I’m a mainstream American comic. I’ve been on Letterman, Conan, Kimmel, Comedy Central. I’ve been in a shitty Sandra Bullock movie. Nothing is more mainstream than a shitty Sandra Bullock movie.”

Kondabolu’s 2016 résumé also includes a conversation with feminist icon and personal hero bell hooks; the greenlighting of a documentary about The Simpsons character Apu and a pilot for TruTV; co-hosting two podcasts (Politically Re-Active with W. Kamau Bell and The Bugle as a replacement for John Oliver); and a nationwide comedy tour to promote the release of Mainstream American Comic.

Though the comedian and his work are certainly informed by politics, Kondabolu prefers not to be labeled, describing his comedy as observational.

“I hate being called a political or activist comedian because it makes me a niche, it puts me in a box,” he tells the Daily Dot. “The second you call me that you’ve taken my power away unintentionally. You’ve just made me a thing that doesn’t hit the mainstream. And I want to. The things that I’m saying need to be heard, they should be mainstream discussions. I don’t say these things because they’re an interesting comedic angle that [is] unique. I say it because I mean it and I feel like it has to be said.”

Kondabolu’s background as an immigrant rights activist and organizer and his education (he received his bachelor’s degree in comparative politics from Bowdoin College in 2004 and master’s in human rights from the London School of Economics in 2008) have certainly influenced his approach to comedy, but it wasn’t until the events of and following Sept. 11, 2001 that the comedian began to develop his political consciousness.

A native of Queens, New York, who was attending college in Portland, Maine, during the attacks, Kondabolu was thrown off by the blatant racism he witnessed in Queens and other parts of the country. He started to become more aware of the politicization of war and propaganda from powerful institutions. This led to an interest in politics, including a college internship in Hillary Clinton’s mail room where he became more privy to the phoniness of the political establishment and subsequently pursued the activist route.

While doing this work in Seattle, he was discovered performing standup, resulting in television and festival gigs and a career trajectory he never thought was possible. Though he approached comedy from an activist perspective, he realized this restricted his ability to see possibilities and connect more broadly with the audience.

For Kondabolu, comedy and its employment are naturally political. Certain topics he discusses—such as colonialism and white supremacy—are not perceived as “normal” to joke about in comedy, meaning his comedy is often placed on the margins where labels are more likely to flourish.

The effect of labeling one comedian “political” and another “mainstream” qualifies the mainstream as apolitical, but all of our experiences are informed by the structures which surround us, this system we are all born into. The way we navigate the world depends in part on our place within these structures and therefore any creative effort borne from this place is naturally political.

As a bit from Kondabolu’s 2014 album Waiting for 2042 exemplifies, political constructs like race are inescapable because they are woven into our culture and experiences. He jokes: “Saying I’m obsessed with racism in America is like saying that I’m obsessed with swimming when I’m drowning.”

While Kondabolu has always received pushback from people who do not understand his perspective, he believes the current Donald Trump-saturated political climate is empowering people to express violence and hatred like never before. He recently re-circulated a year-old joke, which sent violent responses to his inbox.

If “All Lives Matter,” then why don’t we have Universal Healthcare? And why are prisons privatized? And why are there still homeless people?

— Hari Kondabolu (@harikondabolu) August 15, 2015

The irony of white people who say “All Lives Matter” & then threaten to harm me.

— Hari Kondabolu (@harikondabolu) July 13, 2016

Got this threat in my Facebook inbox. I’m assuming this man’s middle name is “White.” pic.twitter.com/MZK1DUXCgt

— Hari Kondabolu (@harikondabolu) July 10, 2016

One joke from Comic recognizes that a lot of animosity from white people results from the fact that they aren’t used to being named and simply don’t understand that “white people” is a metonym for “white privilege” or “white supremacy.”

It does not mean every actual white person, so he asks his audience to start using the phrase white demons, “because nobody’s gonna think they’re a demon, that’s not going to confuse anybody, ya know? And this country was built on white demonry, right? … I’m sure there’s somebody in here who’s thinking, ‘Hari, are you saying all white people are demons and are you saying all demons are white people?’ No, demon, that’s not what the fuck I’m saying.”

This attention to language, its concepts, and how they’re employed is prevalent in Kondabolu’s comedy. While he deconstructs phrases like “white people” on the album, he spends equal time unpacking the absurdity of less politically perceived phrases such as “nocturnal emissions” and “devil’s advocate.” He reads hate mail, his drunkenly conceived will, a college’s promotional flyer for one of his shows, and reviews of that shitty Sandra Bullock movie (2009’s All About Steve). In fact, every track on his new record features some element of language extrapolation.

No matter the subject, Kondabolu is careful with joke construction and the reasons behind the laughter.

“Words matter,” he asserts. “I put a lot of thought into messaging and what it is I’m saying and do I feel good about this joke? Does it represent me? I use words as carefully as I can. So I’m going to gravitate toward things that don’t make sense, that don’t feel like they’re being careful, or have a hidden message that we’re not actually looking at. My ethos is to be thoughtful and careful so if someone or something isn’t, I’m immediately going to try to deconstruct it.”

Another part of Kondabolu’s ethos is his willingness to be more vulnerable with his audience and speak more openly about family and personal relationships. In the past, writing jokes about his immigrant parents seemed cliché, but he’s started to realize the importance of including them.

“My parents are full people,” he says, referring to a joke in Comic about not using an accent when talking about his parents. “I’m gonna talk about my mom because I want to talk about my mom but if you’re going to extract something it’s the fact that I want them to be seen as witty. Not wacky—witty. My mom is funny. If any mom or anybody said [the things she says], it’s hilarious. My mom talks sometimes in jokes. She’s the reason I’m funny. I wanted that to be there.”

Though no topic is out of bounds, the self-described “killjoy who does comedy” refuses to joke about any experience he doesn’t feel he can speak honestly about without hurting others.

“You have to be really thoughtful and careful when you talk about other people’s oppressions because you don’t know those oppressions, you haven’t experienced that, but if you can find ways to be intersectional, it’s crucial,” he says. “And it’s important also for people to see the fact that all this stuff is related and you can be passionate about things that don’t directly, on a day-to-day level, affect you.

“Justice is for everybody… My focus is to make sure each joke is funny, but I can’t help but think about the after-effects based on what I see. … I don’t want to hurt anybody. I want to do the best I can to go after the people that deserve it—the people who are in positions of power. That’s interesting. Being a bully isn’t fucking interesting.”

Kondabolu also performs material that isn’t seen as (overtly) political. In Comic, he devotes time to building a joke around abstract art, noting that art is whatever rich people say it is (politics!) before delving into the meat of the bit—an imagined interaction between Andy Warhol and people from his hometown.

“With this album, you get more of me,” he says. “[Before], I almost wrote jokes like essays just trying to prove a point with a joke. All this [new] stuff is more personal and a way for people to get a sense of who I am. I think people are more willing to laugh at harder things and understand your point of view when they see you as a whole person, when you make them laugh about things that are maybe more in their wheelhouse.”

It’s his ability to jump from jokes about institutional inequality to jokes about his parents to structured bits about abstract art in a single set that defines Kondabolu. And because he’s a political person, that content will continue to pervade his work. Though if politics is the process by which we make decisions to better each other and our communities, perhaps we shouldn’t marginalize work that critiques or employs it.

”I believe in the things I’m saying and I think it’s funny but people who make art that’s critical are always on the margins and they’ve always battled for more space,” Kondabolu explains.

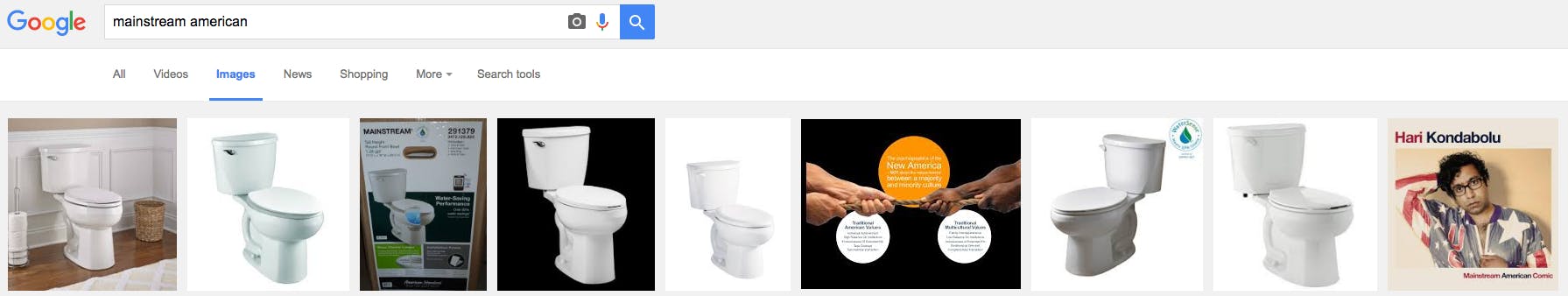

It’s clear his goal is to become a part of mainstream conversation, and in naming his new album, he stayed true to his faith in language. “I love the fact that when people Google ‘mainstream American,’ this album cover and album are going to come up. I want that to be connected to those words,” Kondabolu recently told CBC Radio.

In a perfect display of comedic justice, his album cover does come up. Except he’s jostling for positioning with the perfect embodiment of mainstream America: toilets.

Editor’s note 9:32pm, July 22: An early version of this story capitalized the name of feminist author bell hooks. It has been updated to reflect her preferred capitalization, per conventional usage.