“Video is a very big priority” for Facebook, CEO Mark Zuckerberg told investors on the company’s earnings call on Monday.

It’s a statement backed up by an array of recent developments that make it clear that the social media giant intends to become a leader in the online video space. But Facebook isn’t just looking to broaden its portfolio: Confronted with the declining engagement in key demographics, experts say the company needs to transform itself into an online video hub if it is to remain relevant—and right now, it faces an uphill struggle in doing so.

Unfortunately for video creators, copyright infringement is rampant across the social network, perpetrated by some of the biggest pages on the site, and the company is failing to implement even the most basic software solutions to combat it, or to discipline repeat offenders.

Facebook’s inaction has generated a groundswell of unrest and despair growing among the very content creators and rights-holders Facebook hopes to court, who have serious concerns over what they call the “massive” scale of copyright infringement on one of the world’s most popular social network.

• • •

Every sign points to Facebook’s desire to move into the video space. From the recent introduction of view counts and autoplay on videos, to the acquisition of video advertising company LiveRail for half a billion dollars in July, the social network is clearly gearing up to make its platform more attractive to content creators and improve the overall experience for ordinary users.

For starters, there’s the headline figures: ComCast recently revealed that Facebook saw 12.3 billion desktop video views in August—1 billion more than market leader YouTube. Facebook now claims to see traffic in excess of 1 billion video views daily. Adweek characterises this as part of a “digital power shift” from YouTube to Facebook, writing that video is to be a “core growth area” for the social network.

Content creators are seeing results too—social news company NowThisNews told beet.tv they’d seen a 30-fold increase in video views from July to October, as well as significant increases in user engagement. “We’re only seeing the beginning of the growth of quality video on Facebook,” said company president Sean Mills.

Brands are benefitting as well: “The autoplay feature allows us to increase engagement and exposure with millennials in an undisrupted way, as our content is integrated into consumers’ News Feeds naturally,” a spokesperson for Anheuser-Busch told Adweek.

But Facebook isn’t simply moving into the video space voluntarily. One senior industry figure the Daily Dot spoke to said that the social network needs to make this push if it is to remain relevant. Facebook usage is dropping dramatically among the core teen demographic, as young people turn to Instagram (which is owned by Facebook), Vine, YouTube and other platforms for their social networking and content needs. “Facebook must begin to engage more effectively with millennials,” the industry figure, who asked to remain anonymous, said. “And that means video—especially short-form video.”

In practice, this short-form content means one thing: Viral videos. Many of the clips that rack up millions of views are happy accidents—a baby’s laugh, an over-exuberant dancer, a natural wonder. But there’s big money in the viral business nowadays; the “train selfie kid” got an estimated quarter-million dollar payout, and more and more people are packing in their day jobs to make videos full-time.

If Facebook wants to move into the video space, these are the people it needs to attract. They’re also the people that it’s badly failing.

• • •

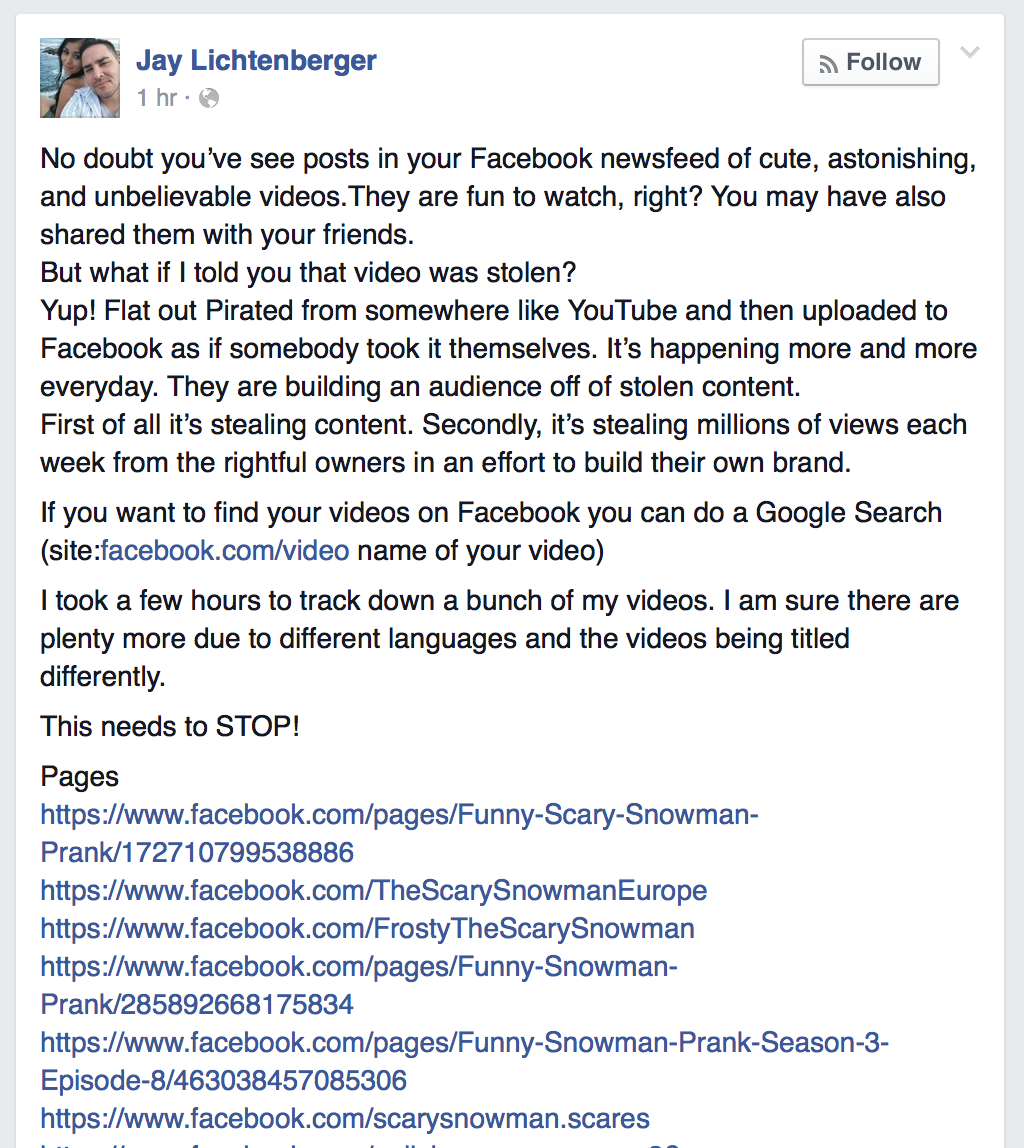

Copyright infringement on Facebook is quite simply “out of control,” Jay Lichtenberger told the Daily Dot. Lichtenberger is a viral video producer, best known for his “Freaky the Scary Snowman” prank series. His clips often rack up hundreds of thousands, or even millions of hits, and making YouTube videos is now his full-time gig.

Lichtenberger is a perfect example of the creators of easily digestible content that Facebook is failing to protect.

While Lichtenberger has a public Facebook page that he uploads videos to, he also sees his content proliferating across the site—entirely without his permission. “It’s happening more and more everyday,” the filmmaker recently wrote in a recent angry missive posted to his private Facebook profile: “They are building an audience off of stolen content. First of all, it’s stealing content. Secondly, it’s stealing millions of views each week from the rightful owners in an effort to build their own brand.”

Lichtenberger rounded off the post with dozens of examples of infringement found with a simple search.

Mike Skogmo, director of communications at viral video licensing company Jukin Media, echoed Lichtenberger’s assessment: “The scale is massive,” he told the Daily Dot. It’s not just small pages flying Facebook’s radar either. Some of the biggest pages on the site, including celebrities and media companies, are uploading copyrighted material illegally—with no consequences whatsoever.

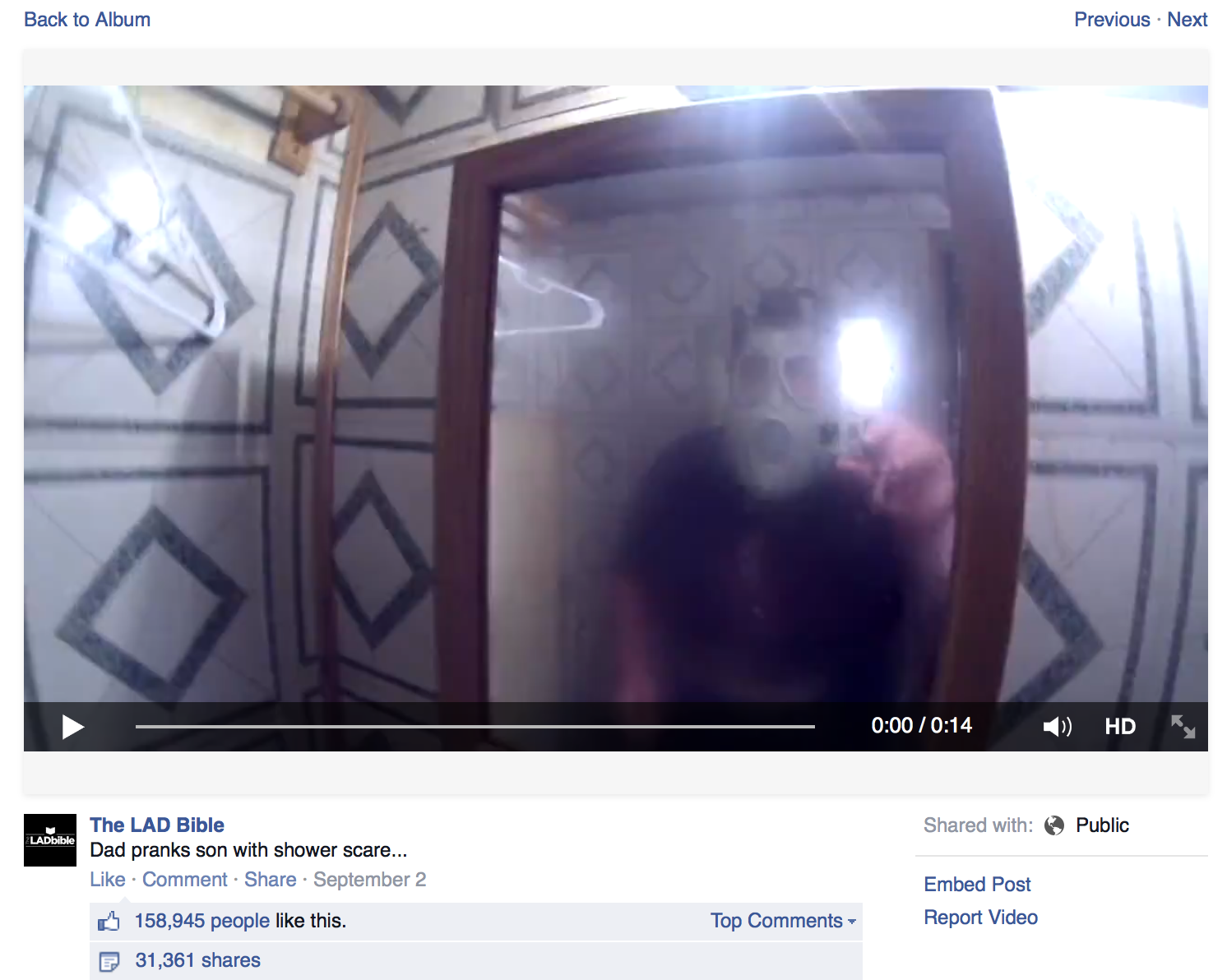

Celebrity gossip blogger Perez Hilton is among those sharing Jukin Media-licensed material without permission on his Facebook page with 1.3 million likes; The LAD Bible is another high-profile offender, sharing stolen content with its 5.6 million followers.

A screengrab of a copyrighted video the LAD Bible uploaded without permission from the rights-holder.

Rapper Ludacris also steals videos and posts them to his page—but there are dozens of other Facebook groups that, while less prominent, have quietly grown huge off the back of copyrighted content. One, BestFunnyVideos2013, has more than 3 million likes—and there are hundreds more just like it.

Those violating copyright law by uploading the videos don’t directly profit from doing so, because Facebook doesn’t have an advertising revenue share plan like YouTube. But this doesn’t matter. Many of the offending pages host videos on Facebook then direct users to their own, ad-supported websites—building their audience off the back of material they don’t own.

Even if the infringers are not seeking to profit, it still harms content creators. “Whether or not the users can directly monetize the content is not as relevant as it seems,” says Skogmo, “since there’s no question that the presence of those videos devalues the originals. Viral videos can earn not insignificant ad dollars on YouTube and can fetch licensing fees for use on other platforms. If anyone can go ahead and find that content ad free on Facebook, that takes views and dollars away from the original version.”

Infringement is endemic across the site, and compounding the issue is the fact there doesn’t even seem to be any repercussions for repeat offenders. Lichtenberger says he has reported some Facebook pages sharing his content without permission a dozen or even more times: Individual videos are taken down, but the pages remain up.

Both Lichtenberger and Skogmo agree that when they do alert Facebook to incidents of copyright infringement, the social network acts quickly to remove the offending items, but the sheer scale of it makes it impossible to effectively police, something only made worse by inadequate search tools.

• • •

So what lies ahead for Facebook? To encourage content creators to adopt the site as a platform, the company “will do what other major distributors are doing to fashion themselves as being the ‘friendliest’ place for video creators,” a senior industry figure who is deeply connected to the video space told the Daily Dot. “I.e., pay outright cash for content, and likely share revenues [from advertising].”

Zuckerberg told investors that video adverts are one of “four major revenue opportunities,” and while no public timeline is available, experts say the acquisition of LiveRail and early experiments with video ads indicate that revenue share programs—as long seen on YouTube—are just around the corner.

The industry figure told the Daily Dot that Facebook must first “gain credibility as being a destination for compelling video” before it can hope to “effectively monetize it.” But if monetization plans are implemented without serious reform to the way the Facebook addresses copyright infringement, then the very people the social network hopes to appear “friendly” to—short-form, viral video producers—face the prospect of seeing others profiting off the theft of their work.

If that happens, Lichtenberger, a prime example of the type of content creator Facebook needs to court, says he’ll be “extremely upset.” And more than that—he’ll “look into filing a class action lawsuit.”

• • •

There’s a solution, however: Content ID. Software that automatically scans video for copyrighted content, Content ID has long been in place on YouTube. Video host Vimeo also more recently adopted it, telling Billboard that they “want to empower people … with full understanding of what’s allowed under the law.”

Identification of offending material doesn’t mean an automatic deletion: On YouTube, rights-holders can decide whether they’d like material flagged up by the system monetized for themselves, or muted, or taken down—or even left alone.

What this mean would mean in practice is that, if a content creator without an established Facebook presence discovered another, extremely popular page was hosting one of their videos, the creator could decide to leave it up but to run adverts beside it, benefitting from the page’s exposure and making a profit off the infringement.

Content ID’s implementation would solve rights-holders’ concerns overnight. Content creators would be able to automatically and effectively police their content, and it would stem the tide of opportunistic thieves that currently plague the social network.

Facebook is also pushing to have publishers post content directly into the site, indicating their ultimate ambition is to be the home, rather than just aggregator, for all content online—not just video. Ad revenue sharing would once again be an incentive to publishers and content creators—but without software monitoring solutions like Content ID this just promises a future where copyright thieves can profit easily off the work of others.

So why hasn’t Facebook already implemented it? The company did not respond to multiple requests for comment, but the industry figure the Daily Dot spoke to said that they “don’t know why not yet, because it is critical for all video distribution players to be content and creator ‘friendly’”—and believes we should expect Content ID “soon.”

There are, of course, problems with overzealous application of copyright law. YouTube’s own three-strikes implementation has been heavily criticized as open to abuse, and has reportedly been used to censor legitimate criticism of copyrighted content, such as video games, which are protected under the Digital Millennium Copyright Act’s (DMCA) fair use policy.

But if YouTube’s implementation is too extreme, then Facebook’s current situation is quite the opposite. The social network is a free-for-all: Rights-holders are being overwhelmed by the sheer scale of copyright infringement; creators are having their livelihoods stolen from them.

These creatives risk being put off the social network for good, despairing at how digital bandits are able to take advantage of Facebook’s apparent indifference to the concerns of the very people it desperately wants—and needs—to attract.

Illustration by Jason Reed