Finally, in Cuba and the Cameraman, a capable filmmaker provides a full document—45 years and a thousand hours of film in the making—that displays an on-the-ground humanistic version of Cuban progress, or lack thereof.

Director Jon Alpert’s latest film premiered on Netflix Friday—just before the anniversary of Fidel Castro’s death. Successfully utilizing a slow-burning, but revealing tack, Alpert’s labor of love turns into his best work.

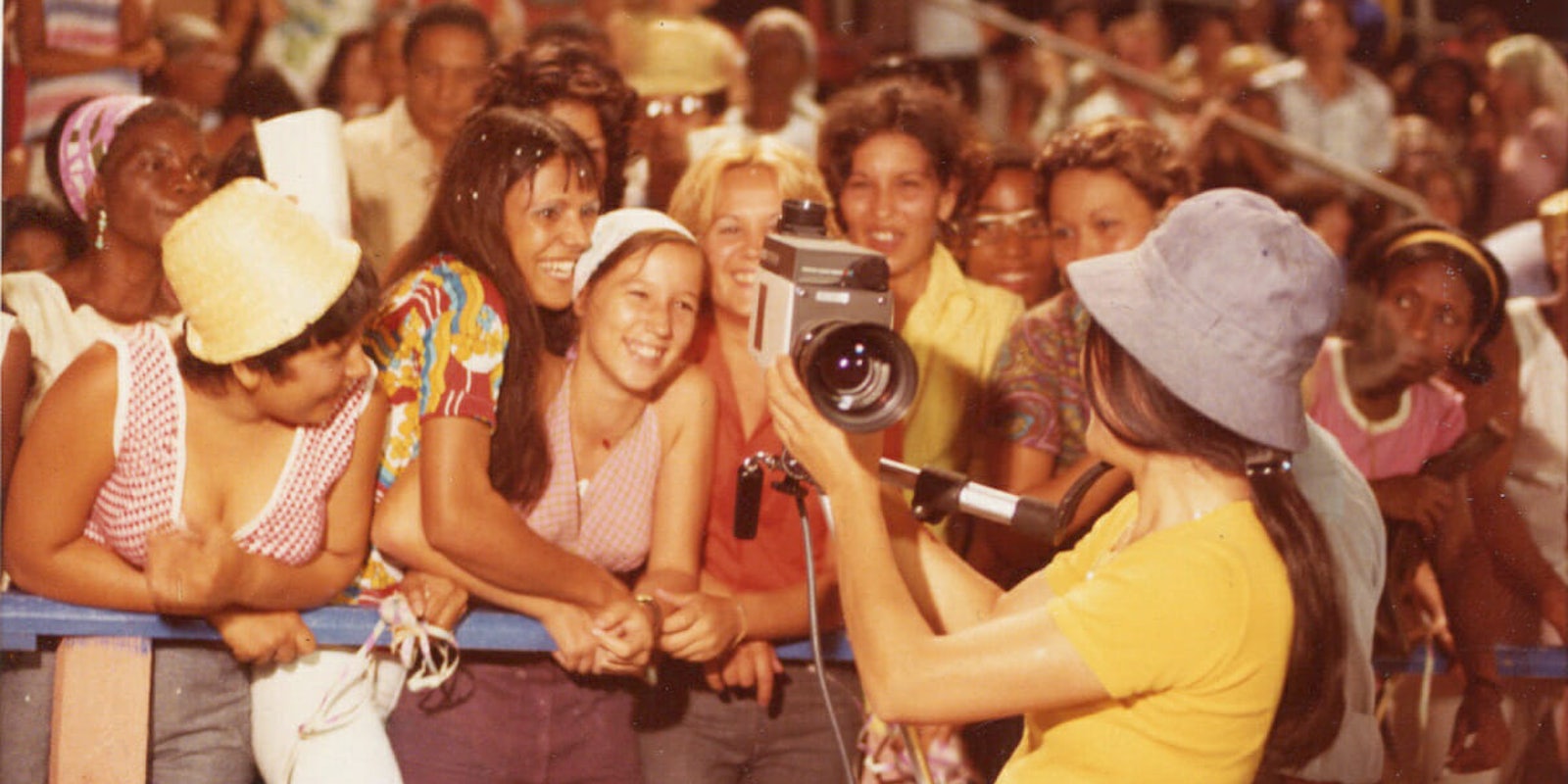

Alpert, an award-winning journalist, began visiting Cuba in 1972 as a documentarian taking advantage of new video technology, trying to see if Castro’s socialist revolution was, in fact, creating better lives for Cubans. Visit after visit, the investigative reporter entrenched himself in the country’s culture, filming the ordinary Cubans, and eventually earning rare favor with Castro himself.

The film commences with the announcement of Castro’s death, the roads empty with people mourning their leader.

Alpert warms the story through his co-founding of the Downtown Community Television Center, wherein in the ’70s, he exposed sweatshops and other labor struggles in New York City. There’s footage of a young Alpert talking to angry and distressed laborers. Intrigued by Cuba’s socioeconomic programming, Alpert wanted to know if the novel ideas he’d read about were true: Was Castro implementing the social programs he’d fought for?

He’s initially pleased to see the elevation of all social services above what he’d seen stateside. Children in schoolhouses had desired to become psychologists, engineers, and doctors. He saw infrastructural industry and agriculture, making friends with a set of older farming brothers working the lush Cuban countryside.

Eventually, he’d interview Castro and accompany him on an October 1979 trip to New York for his United Nations speech.

Then, as one predicts, things begin to go pear-shaped over the subsequent decades as Cuba descends into social and economic decay. Unique in this story are the informative perspectives given to Alpert, who’s developed a deep trust with his subjects. Each visit back, he locates them at different stages, getting updates on their lives, filming microcosmic snapshots of Cuban life.

There are periods, primarily through the late ’80s and into the Clinton era, where clean water and basic food staples become scarce, to the point that oxen from the older farmers’ lots were stolen and slaughtered. A man Alpert had met in Havana was jailed for years, accused of working in the black market. A woman, at a bar with no alcohol, laughs at Alpert when he asks about the last time they had meat in their town.

The Mariel boatlift of 1980 is also touched upon, looking into who Castro evicted from the country. Castro had emptied out prisons and mental institutions, more or less sending Cuba’s most volatile onward to Miami.

Alpert’s sugary affection for Cuba, and patience with its rising and falling, and Castro individually, will rub many the wrong way. But this is Alpert’s story. He makes no bones about his leanings, and make no apologies, which lend significantly to the documentary. Whatever your politics, it’s a stunning achievement.

Still not sure what to watch on Netflix? Here are our guides for the absolute best movies on Netflix, must-see Netflix original series and movies, and the comedy specials guaranteed to make you laugh.