Less than a week after Aaron Swartz took his own life, filmmaker Brian Knappenberger found himself surrounded by friends and colleagues of the 26-year-old Internet activist. Knappenberger was attending a computer symposium in New York City, where he was scheduled to answer questions about hacktivism, a topic he’s well-versed in.

Knappenberger’s the writer and director of We Are Legion: The Story of the Hacktivists, a 2012 documentary that follows the exploits of Anonymous, from its origins on 4chan to the arrests of the Paypal 14 during Operation Payback in late 2010. Most recently, Knappenberger directed a public service announcement for the Electronic Frontier Foundation, featuring Oliver Stone, John Cusack and four government whistleblowers, that called for an end to mass surveillance by the National Security Agency.

A sense of mourning overshadowed the New York City symposium, Knappenberger recalled. Under different circumstances it would have probably been a cheerful reunion. At the conference, he sat between friends Gabriella Coleman and Joshua Corman, while listening to Quinn Norton, an American journalist who was Swartz’s partner for several years. At the time, another documentary was far from his mind.

The next day, Knappenberger attended and filmed a memorial at Cooper Union’s Great Hall. Almost 900 people showed up to honor Swartz. Naturally, those who knew him were overcome by a profound sense of loss and heartache, but other emotions coursed through the crowd as well.

“Aaron was targeted by the FBI,” Roy Singham, Swartz’s former employer, said while addressing the crowd.

Singham spoke about the need to hold Swartz’s “tormentors” accountable for their actions and read aloud a letter he received from Indian journalist Palagummi Sainath. “This was—and I say it without hesitation—not suicide. It was murder by intimidation, bullying, and torment,” the letter said.

For the two years before he took his own life on Jan. 11, Swartz lived with the knowledge that he might spend up to 35 years of his life behind bars. Federal prosecutors aggressively pursued the young activist, throwing at him the full weight of the Justice department.

The computer crimes Swartz was accused of didn’t even involve the theft of anyone’s personal information. There were no classified documents, credit card numbers, or executive’s emails. The criminal action, alleged by the prosecutors, was that Swartz downloaded too many academic journals from JSTOR, a digital library, which he was authorized to access on the MIT network. Prosecutors claim that Swartz violated the site’s terms of service by writing a script to copy the articles to his laptop en masse.

Even after Swartz returned the data he’d downloaded and JSTOR indicated they had no desire to pursue charges against him, the government refused to back down.

Eventually, the felony charges deteriorated Swartz’s emotional state—the Secret Service noted Swartz’s “depression problems” in its report—and ruined him financially. Even his friends had been issued subpoenas. “Every word you speak or write can be used, manipulated, or played like a card against your future and the future of those you love,” Norton said later, describing life inside a federal investigation.

Following Swartz’s death, his partner Taren Stinebrickner-Kauffman authored a blog post titled “Why Aaron Died.” In the introduction, she shares her recollection of a dream. Swartz sat next to her on the bed, atypically struggling to read the words of a book. She asked him to explain his decision to take his own life. He told her, “I’m dream Aaron… I can’t tell you anything you don’t already know.” She calls the experience a dream nightmare.

“I believe that Aaron’s death was caused by a criminal justice system that prioritizes power over mercy, vengeance over justice,” she wrote, “a system that punishes innocent people for trying to prove their innocence instead of accepting plea deals that mark them as criminals in perpetuity; a system where incentives and power structures align for prosecutors to destroy the life of an innovator like Aaron in the pursuit of their own ambitions.”

Eventually, Knappenberger realized that he needed to tell the story of Swartz, whose early work, most notable the development of the RSS, is inseparable from the chronology of Internet history.

“I thought maybe at first it was a short film,” the director said, “but the more I dug into it the more I became interested in it and I realized as a whole, it was definitely a feature film.”

Many have argued Swartz’s tragic story highlights the disparity of a crumbling American legal system, most specifically the ill-conceived Computer Fraud and Abuse Act (CFAA) under which Swartz was prosecuted. The CFAA is an outmoded law, replete with ambiguous language, devised almost 30 years ago to criminalize certain computer-related acts in the wake of unwarranted hysteria surrounding the Hollywood movie WarGames.

“There’s no question that the CFAA needs reform,” Knappenberger said. “That’s a really complex issue, because I think even tech companies are resisting that. It’s just an outdated law, there’s no question about it. It’s being used as this one-size-fits-all incident hammer. They can just go after anything marginally hacker-related. We look at a bigger, broader picture of the Department of Justice system and ways that it’s broken, this kind of overwhelmed system—basically overwhelmed by the Drug War more than anything.”

Most recently, the CFAA was applied in the case of Jeremy Hammond. In 2012, a judge told Hammond that the charges against him could result in life-imprisonment. After pleading guilty, he now faces a maximum sentence of 10 years for his involvement in the 2012 hacking of Stratfor, a private global intelligence firm.

“Ninety-seven percent of people now are forced to plea out,” said Knappenberger, referring to an oft-cited statistic used in Missouri v. Frye. “ It’s absurd to think that ninety-seven percent of the people that are in our court system are guilty. That can’t be true. So, obviously, there’s something majorly wrong with our system. I think Aaron’s story speaks to that.”

He described his upcoming film as being in the same vein as We Are Legion. That film he agrees was the beginning of a battle. “It was basically made during the ‘Summer of Lulz’, the same year that Time magazine had ‘The Protester’ as person of the year. But, this has come when we’ve just witnessed this incredible crackdown on activists and journalists, and obviously the NSA activity.”

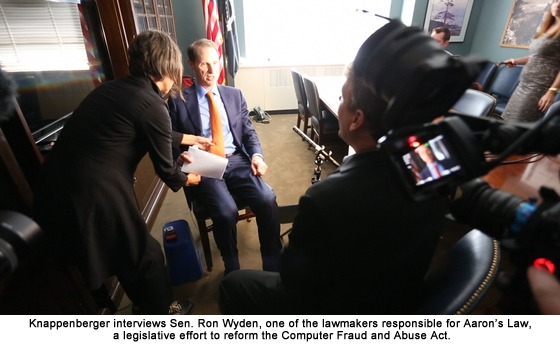

The Internet’s Own Boy offers a much more thoughtful and intense personal story. “This is a very different kind of darker side of things,” Knappenberger said. Along with footage of Swartz himself, the documentary, scheduled for release in 2014, features interviews with close friends, colleagues, and a variety of digital activists, including Ben Wikler, David Segal, Christopher Soghoian, Cindy Cohn, and Sen. Ron Wyden, who’s working on an overhaul of the CFAA, dubbed Aaron’s Law.

Knappenberger’s committed to a Creative Commons approach in regards to file-rights of the film, which is fitting given that Swartz aided in the development of that licensing format.

Yet, Knappenberger resists the notion and the easy narrative that Swartz was a martyr for any cause.

“I think he just cared and was super curious about the world. I think that’s accessible to everybody,” he said. “A part of that martyr-making is to say, ‘Oh, if we could only have more people like Aaron.’ It’s like… well, yeah, but you could be like Aaron. That’s not out of reach.”

Swartz had a profound impact on the people who knew him and the way they apply their skillsets on a daily basis.

“How do you use what you’re great at to make the world a better place? How are you most effectively going to use your skills in the time that you have?” Knappenberger asked. “You certainly hear that in the startup world, but what does that mean and how many startups really make the world a better place. Everybody says that.”

Swartz took it one step further. He asked the hard questions, then he created his own answer.

Photos via Brian Knappenberger