It almost feels unfair to describe A Knight’s Tale, released to theaters May 11, 2001, as an underrated gem. Surely, everyone knows it’s a masterpiece, right? Written and directed by Brian Helgeland (L.A. Confidential), it’s an eclectic blend of sports movie, rom-com, historical drama, and fairytale. Its pitch-perfect tone is clear from the opening scene, when our hero William Thatcher (Heath Ledger) learns that his boss, an aging knight, has died before an important joust.

“The spark of his life is smothered in shite,” quips William’s long-suffering friend Roland. “His spirit is gone but his stench remains.” Roland, William, and their friend Wat are lowly squires, and together they hatch a plan to cheat the medieval class system: William will impersonate Sir Ector, finish the joust, and collect the prize money. “I’ve waited my whole life for this moment,” says William, with starry-eyed optimism. “You’ve waited your whole life for Sir Ector to shite himself to death?” replies Wat with a grimace, puncturing the sentimental mood. Then we cut to a dynamite example of scene-setting: a jousting tournament where the crowd beats out the tune of We Will Rock You by Queen. Buckle in, the film seems to say. This is what you’re in for.

We’re now used to hearing jokily anachronistic music in historical dramas, but 2001 was arguably where the trope kicked off, with A Knight’s Tale coming out alongside Moulin Rouge and Shrek. A Knight’s Tale remains one of the most successful examples to date, partly because it’s free from irony. There’s no nudge-nudge-wink-wink genre savviness in the moments where Bowie and Queen show up in the soundtrack. The whole film is seamlessly sincere.

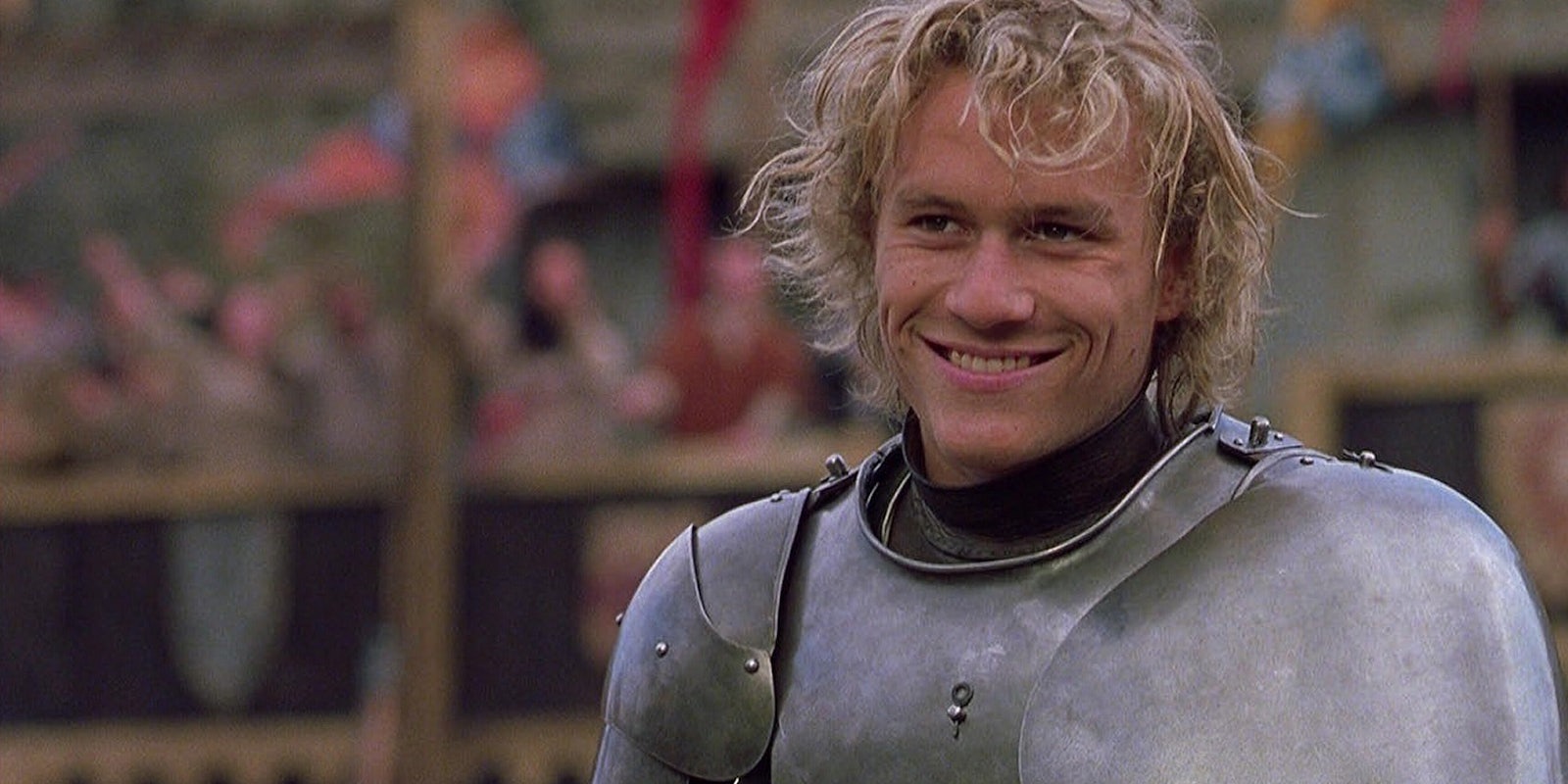

A Knight’s Tale earned middling reviews at the time, but is now something of a cult favorite—a movie that millennials watched as kids in the early 2000s, and is just as wonderful two decades later. The same can’t be said of many other nostalgia-fueled rewatches. 21-year-old Heath Ledger is luminously charismatic in the lead role: handsome, goofy, vulnerable, and armed with the determination of an Arthurian hero. Better known for his more serious dramatic roles, this and 10 Things I Hate About You highlighted his incredible comic timing. And as you move down the rest of the cast list, you realize this is a rare film where the casting director truly struck gold. Alan Tudyk and Mark Addy are perfectly chosen as William’s larger-than-life sidekicks, ripped straight from the pages of a Shakespeare comedy —or more accurately Chaucer since the film was loosely inspired by The Canterbury Tales. Paul Bettany, of course, plays the man himself.

To my mind, this is still one of Bettany’s finest performances. He’s a total scene-stealer as Geoffrey Chaucer, combining theatrical panache with a hint of tragedy. A bitchy intellectual who self-sabotages with a compulsive gambling habit, and gleefully incites a homoerotic feud with the rageful Wat.

When Chaucer first arrives on-screen, he’s fully nude after losing all his clothes to debt-collectors, gradually redeeming (and clothing) himself by becoming William’s business manager. Helgeland’s screenplay is particularly memorable here, giving Bettany a series of overblown speeches in the style of a shit-talking prizefight announcer. Previously a stage actor with the Royal Shakespeare Company, he struts up and down the jousting yard, plumbing the depths of his lung capacity. “We walk in the garden of his turbulence!” Chaucer roars at a crowd of bemused peasants, advertising William’s athletic prowess. It’s easy to see why this was Bettany’s breakout role in the US, with Helgeland showing his audition tape to other directors until Ron Howard cast Bettany in A Beautiful Mind.

Elsewhere in the cast, Rufus Sewell plays gloriously to type as the despicable Count Adhemar, while the film’s least recognizable face is probably Shannyn Sossaman. She co-stars as the graceful yet piercingly witty Jocelyn, Will’s love interest. As is often the case for this kind of film, she doesn’t get as much to do as the men—although fortunately, we do have another female character in the form of Laura Fraser’s no-nonsense blacksmith Kate. She’s an instantly likeable figure, exemplifying the film’s attitude to history: It’s totally plausible for a woman to work as a blacksmith in 14th-century England (unlike what many medieval films would have you believe), but at the same time, one of Kate’s best gags involves her engraving a Nike swoosh onto William’s armor.

Jocelyn’s main role is to be the object of William’s affection, nudging him into a journey of self-improvement. Initially attracted to her beauty, he learns to value her as a partner rather than a prize. Fairly standard stuff for this kind of story, but it’s aged surprisingly well—perhaps because the film didn’t opt for a corny girl-power route, and leaned into the chivalric nature of their relationship instead. William must prove himself worthy of knighthood and of a lady’s love, in a fairytale romance that largely works because Heath Ledger is so convincingly, boyishly smitten.

Structurally speaking, we’ve seen this type of underdog story before, populated by a cast of familiar archetypes. But A Knight’s Tale‘s strength lies in its execution. There’s no sense of formulaic laziness here. Every scene thrums with enthusiasm and sincerity, whether it’s Bettany’s hysterical speeches, Ledger’s earnestness, or the laddish slapstick comebacks of the two squires. The dialogue sparkles, and Helgeland made a smart choice by abandoning any attachment to historical accuracy. Because what is “accuracy,” anyway?

Plenty of directors tout their obsessive research into authentic props and costumes, while casting actors who conform to very modern beauty standards, in stories that appeal to modern sensibilities. Others interpret “historical accuracy” as an excuse to focus on straight white men, which is historically and ethically wrong. Here we have a film that embraces the squalidity of Chaucerian humor and the lofty ideals of chivalric romance, while also being a straightforwardly delightful early-2000s comedy romp. Attention is paid to certain details like heraldric symbolism and 14th century jousting rules, yet Jocelyn wears yellow eyeshadow and dances to Bowie. Like so many outwardly simple artistic successes, there’s a lot going on beneath the surface in A Knight’s Tale, which is why it makes for such a satisfying rewatch.

This post has been updated.