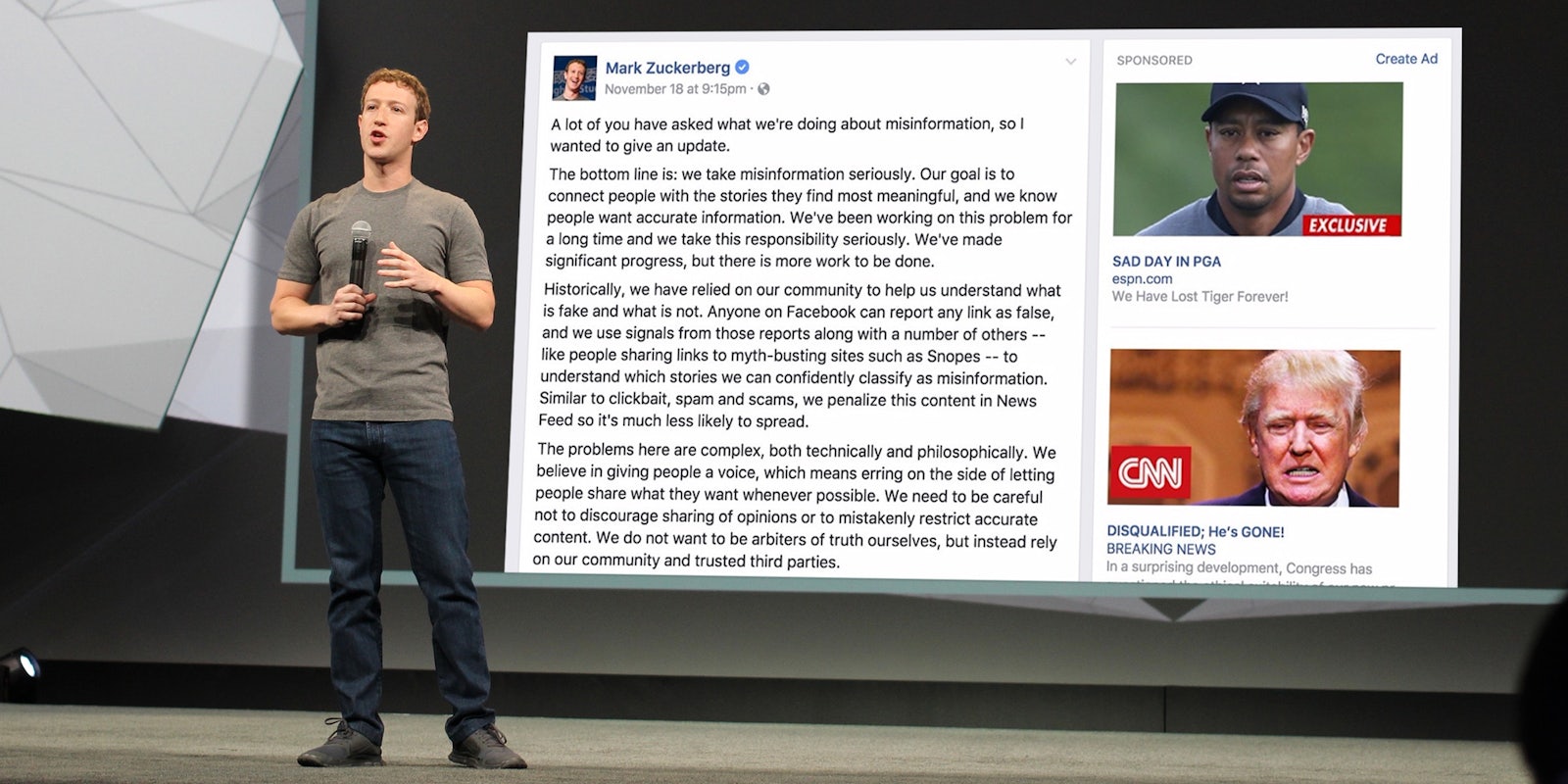

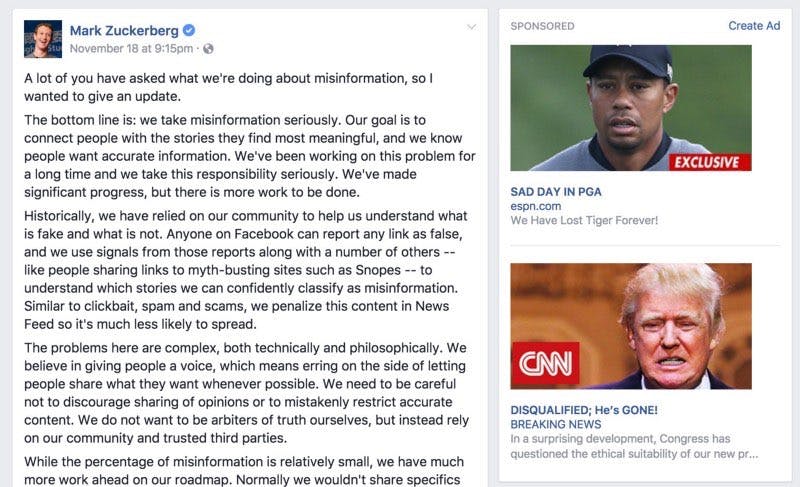

Ev Williams, a co-founder of Twitter and Medium, has a good reason to be interested in what Mark Zuckerberg has to say about deceptive news. But when he went to read Zuck’s Facebook post downplaying the fake news crisis, he was more interested in what else he saw on the page.

Right next to Zuckerberg’s plan to decrease fake news, there were two sponsored—in other words, paid—ads. One pretended to be an ESPN.com story and implied Tiger Woods had died or permanently retired.

“It goes to espn.com-magazine.online and attempts to sell a muscle-building supplement using ESPN branding and a fake news story,” Williams wrote on Medium.

The second looked like a CNN story claiming the U.S. Congress had “disqualified” Donald Trump and that “he’s GONE!” But the link led to an ad for… toe strengthening exercises?

Fake news, it seems, is not just in your news feed. It’s also hiding in the adjacent ad space.

Zuckerberg can make noise about “erring on the side of letting people share what they want,” but he’s doing it with deceptive ads on the very same page. He’s right in saying that the fake news problem is “philosophically complex,” but one of the complexities of it is that, philosophically, public companies believe in making money for their shareholders. And money doesn’t always equate to truthfulness.

Earlier this month, Facebook’s stock took a dip when CFO David Wehner told investors the company was hitting its limits in terms of ad load—how many ads it can cram onto a page. Ad sales growth was expected to “meaningfully” decline.

How much of that full ad load is deceptive articles pretending to be from real news websites? And how would investors react if those sales all went away? These are questions the social network will have to confront now that it has admitted fake news is a problem.