The debate over the recent trend of attempting to duplicate Wes Anderson’s distinct aesthetic—whether through detailed TikTok homages or more controversial AI-generated renditions—is returning as Anderson’s latest movie, Asteroid City, finally arrives in theaters.

Anderson’s movies are known for sneakily telling emotional stories while leaning into a purposely quirky and artificial aesthetic in their production design; he’s worked with several production designers over the years, but Adam Stockhausen has been his go-to production designer since 2012’s Moonrise Kingdom.

Asteroid City is no exception: The film leans into the artifice by framing its primary story of an alien visiting a desert town as a televised production of a play written by a playwright. The play’s production is filmed in color with locations that feel like sets, a roadrunner that pops up looks like a puppet (because it is), and pages of the script are shown telling the audience which scenes are taking place. The TV special—including an explanation from the special’s host (Bryan Cranston) about Asteroid City’s conceit—and scenes around its creation are shot in black-and-white. It’s incredibly effective.

As is the case with most Anderson movies, the release of a new one drums up renewed discussion on Film Twitter about his aesthetic, its effectiveness, and what it’s trying to accomplish. This time, Asteroid City’s release was preceded by more than a month of people online trying to recreate the quirks of Anderson’s movies in their own lives or with the aid of AI technology.

In a video posted in May—soon after the TikTok meme and AI trailers went viral—by TikToker @unofficialivy, she argued that Anderson was probably having a bad day after the emergence of an entire trend of people recreating the look of his movies in bite-sized form.

“Imagine working your entire career to develop this iconic style of film that makes you a household name,” she said. “Wins you awards. It takes you years to produce a film, but when you do, everyone rushes to see it. They talk about how talented you are. That iconic style that you’ve developed. It’s timeless. It’s amazing.”

For her, some of the recreations worked better than Anderson’s.

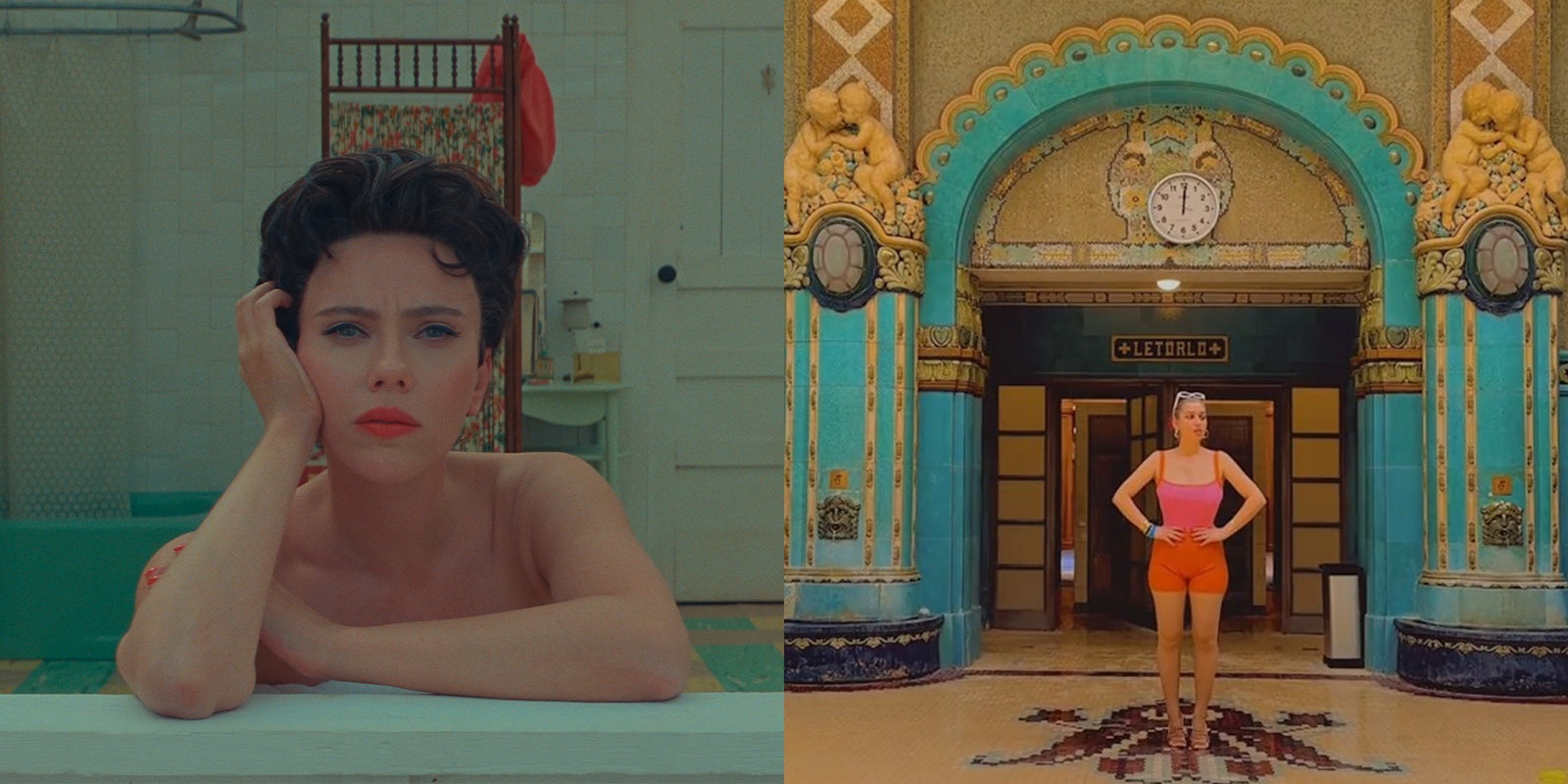

“And then overnight, it becomes a TikTok trend, and everyone with a TikTok account is duplicating—quite well, to be honest; I’ve seen some good ones—that iconic style,” she added, pointing to an example of an Anderson-style TikTok that worked for her as well as The Grand Budapest Hotel. “Completely invalidating your life’s work, because, turns out it just wasn’t that hard.”

@unofficialivy’s video, which received more than 1.5 million views, was posted weeks before Asteroid City debuted at Cannes and more than a month before it would be released in theaters. (It’s in limited release now and will get a wider release on June 23.) But as the public has started to see Asteroid City, @unofficialivy’s video hit a new audience: Cinephiles and Wes Anderson fans outraged by her take.

For them, what those Anderson-style TikToks are missing is the substance. It’s one thing to copy his style; you can argue about how well those recreations are executed. But it’s not enough to have people standing in the middle of a shot or staring directly at the camera. Those videos haven’t captured the wide breadth of emotion, warmth, comedy, and sentimentality evident in so many of Anderson’s movies.

“Imitation is the sincerest form of flattery that mediocrity can pay to greatness,” @ViceApologist tweeted.

Others posted different shots from Anderson’s other movies to show how much is conveyed in some of the shots he brings to life.

And they weren’t impressed with the example @unofficialivy cited as being as good as The Grand Budapest Hotel, a movie usually considered to be one of Anderson’s best.

For what it’s worth, Anderson isn’t much of a fan of the TikTok trend. In an interview with the U.K. publication The Times, he explained that he avoids those videos even when sent directly to him.

“If somebody sends me something like that I’ll immediately erase it and say, ‘Please, sorry, do not send me things of people doing me,’” he told The Times. “Because I do not want to look at it, thinking, ‘Is that what I do? Is that what I mean?’ I don’t want to see too much of someone else thinking about what I try to be because, God knows, I could then start doing it.”