Twitter is exactly the same as high school, the office, or pretty much any other social confine: people jump into cliques and stick to them.

That’s according to a recently published study by the School of Biological Sciences at Royal Holloway and Princeton University. Researchers looked at conversational tweets (i.e. @replies) for around 250,000 users. In total, they examined more than 200 million tweets sent between Jan. 2007 and Nov. 2009.

As the Guardian reports, the “largest group found in the analysis was made up of African Americans.” That community sent 90 percent of @replies between themselves. The group also tended to shorten words by replacing the “ing” suffix with “in” or “er” with “a.”

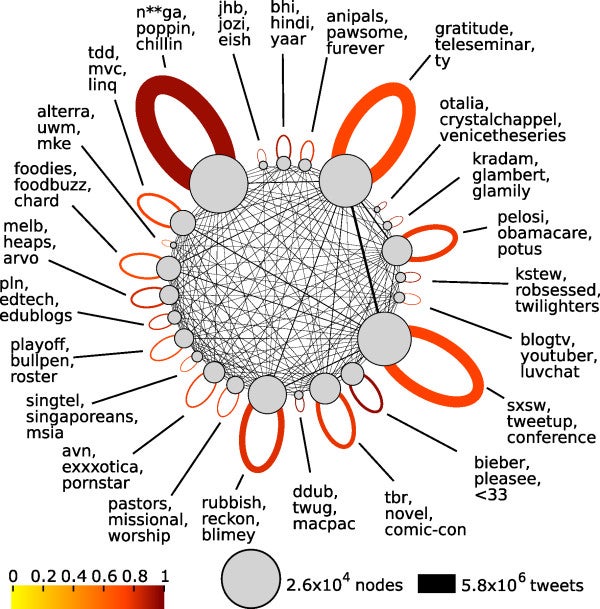

This figure visualizes how the communities are divided by language use, and how they interact with each other.

According to the researchers:

The top word given for each community is the most significant one in that community. Users send a high proportion of their messages (0.91) to other users within the same community. Circles represent communities, with the area of the circle proportional to the number of users (>250 shown). The widths of the lines between circles represent the numbers of messages (>5000 shown) between or within community. The colours of the self-loops represent the proportion of messages that are within users from that group. A word has been starred to avoid offence.

A spreadsheet does a better job of making sense of that data. After African Americans, the next largest groups are South by Southwest conference attendees, the “social movement” collective, Brits, comics and novels fans, American right-wing community, software developers, and foodies.

Another social group revealed a different linguistic phenomenon. “The Justin Bieber fans have a habit of ending words in ‘ee’, as in ‘pleasee’,” Prof. Vincent Jansen said. That falls in with an Atlantic report about many users lengtheniiiiing their woooooords.

Researchers hope, according to the Guardian, that the project data can reveal a more in-depth look at how language is changing among Twitter communities, with a view to finding new ways to engage with them beyond hashtags.

That certainly brings a marketing element into play: marketers might soon know how to tap into target demographics beyond an identical Promoted Tweet being blasted to all of Twitter’s users.

More importantly and significantly for the community, the study provides an intriguing look at changing language on Twitter.

Photo by GS+/Flickr