I hated playing This War of Mine. It’s unfair, brutally difficult, and depended on randomness more than my own skill. It felt impossible to win. And that makes it brilliant.

This War of Mine is based on the accounts of civilian survivors of war, from places like Kosovo in the late 1990s to more contemporary conflicts in Libya and Syria. This War of Mine was created by a Polish developer, 11 Bit Studios, and one of the game’s writers has even cited stories of the Nazi occupation of Poland during World War II as an inspiration for the game.

This War of Mine is presented mostly in cross-sections of bombed-out buildings in the fictional, ostensibly Eastern European city of Pogoren. The government has surrounded a group of rebels who are trapped in the city, and the blockade has cut off supply lines. Gunfire and explosions in the distance are a constant background noise, and the art resembles a charcoal drawing with muted use of color, which plays nicely into the idea of a ruined city.

We might expect a game with this heavy a theme to be more appropriately presented as an interactive text adventure developed in Twine, or as an experience like Gone Home, which defies the traditional gameplay experience. This War of Mine, however, is decidedly a traditional game in terms of design. We might even identify it as part of the survival horror genre.

There are inventory screens, trading with non-player characters (NPCs), and light strategic elements. This War of Mine reminded me of State of Decay in that scavenging for supplies and stealth are central tenets of the game. “Why, then, is it impossible to win?” I asked myself as I tried and failed multiple times to keep my group of survivors alive. I’m not even sure that there is an ending to This War of Mine, where the government finally breaks through the rebel lines and liberates the city.

I was so frustrated. If This War of Mine took such pains to present itself not as some alternative experience to a traditional game, why did skill not seem to matter at all in my success or failure? Why was the capricious nature of what felt like random item generation responsible for whether my characters lived or died? Why, if This War of Mine was supposed to convey some deep message, wasn’t it a Twine game, or presented in some other form that wouldn’t make me feel like it was supposed to be winnable?

“Why even make a harsh story about surviving war into a video game?” I yelled out loud after trying and failing yet again. And then it occurred to me. That’s precisely the point. Why is war ever turned into a video game?

You begin This War of Mine with three civilian characters hiding in a shelter that’s crumbling with broken floors and walls as a result of the constant shelling. Hidden among the rubble are pieces of wood, and components like nails, duct tape, plastic containers, and scrap, from which you can make beds, or simple heaters and cooking stoves.

The most important areas in the shelter are the kitchen where you store food, and the medicine cabinet in the bathroom where you store bandages, bottles of medicine, and simple, herbal medications. Food and injury are the ultimate arbiters as to whether your survivors live or die, no matter how many devices you’ve built or how many building materials are at hand.

Daytime is for healing, eating, and resting, to get your characters ready for the evening. NPCs may show up at the door offering opportunities to trade, and they are miserly in the deals they offer. If you’ve built a radio, you can listen to reports, which more often than not are increasingly dire messages about the mounting desperation of other civilians trapped in the city.

Nighttime is for scavenging. You designate survivors to sleep, stand guard, go out to look for supplies. Sometimes you find homeless people at the locations you search. You might know in advance that survivors who don’t want to trade are at the location, and you can decide whether to try stealing from them or not. Other areas are under fire by snipers or occupied by rebels or the military.

Once you arrive at your location, This War of Mine is about stealth, peeking through keyholes to see if anyone is on the other side of doors, or hiding in empty doorways to avoid detection. If you steal from someone, you might get shot. You may find someone willing to trade with you. You will almost always find building materials. You will rarely find the food and medicine you need.

When you return home, you pray that the report of the evening’s events doesn’t include notice that the shelter was raided at night. The more people you stood on guard during the scavenging run and the more weapons you’ve built for them, the less nighttime raids on your shelter are likely to succeed, and the less likely your survivors will be injured while fending off the assault.

As the horrible conditions start piling on, or if characters starve to death or are killed while scavenging, your remaining survivors will get depressed, and their ability to work suffers. If your characters are very hungry or exhausted, they may abandon whatever task you set them to, such that you have to repeatedly give them the order to continue. Eventually they become uncooperative, and you may as well start the game over, because your survivors are already dead, in any honest appraisal.

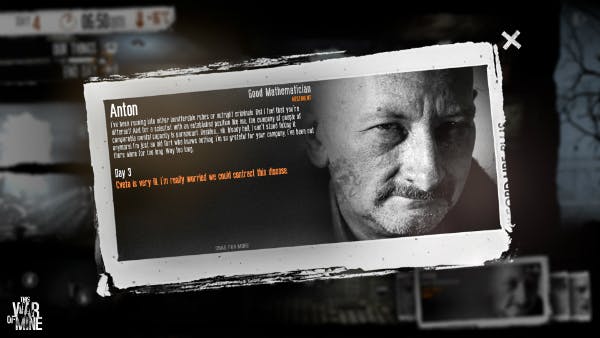

This War of Mine tries to humanize its characters by using real photographs to depict them in information screens, and on the little cards in the lower right-hand corner by which you select which character to control. The characters blink on those little cards, which caught me off guard, and was a nice touch. It was something to make them look less like photos of pure avatars.

Whether or not you relate to anyone in This War of Mine will depend on how sympathetic to suffering you are, because the game itself doesn’t help you to know anyone. There is no spoken dialogue, only word bubbles which are mostly about conveying character state, i.e. their mood—how much you can depend on them to reliably work or how sick they are. One could argue that looking at the characters in This War of Mine as nothing but playing pieces represents the sort of dehumanized thinking one might expect among desperate survivors.

The first time someone came to the door of the shelter asking me to help unbury someone who was trapped in the rubble after a building collapsed, I decided to volunteer and see what the effort brought me. The answer was nothing, so the next time someone asked for help I turned them down, so as not to lack a body during the day to get work done. I turned down pleas to join my group of survivors, because I didn’t have enough supplies and couldn’t afford to take on another mouth to feed.

Even without anything resembling character development, there were times when the potential, moral repercussions of my decisions were uncomfortable to think about. There was an episode where a woman came to the door. She was hearing stories about looters raping women, and while she could lock the door at night, people could still get in through the windows. She wanted help boarding them up.

I told her to wait a second, as I wanted to finish some work I was doing in the shelter. I figured she would wait until it was close to night before she left. I was wrong. She slowly walked away from the front door, lamenting that I wouldn’t help her. I ran downstairs to try and go with her, but she was gone.

In another episode, I helped a man who had been shot by a sniper get back to his building. I heard an infant crying. It turned out that the man I had helped was the infant’s father. I decided not to scavenge in that building anymore, even if the items weren’t clearly marked as this man’s property, just to keep my conscience clear.

I outright stole from people only once. The house belonged to an elderly couple. The husband plead with me not to take their things. His wife fell to the floor, clutching her legs and begging me not to hurt them. I did not repeat the experience of theft again, no matter how desperate my survivors became.

We all know that most video games about war are preposterous. They have names like “Modern Warfare” or “Advanced Warfare” or “Battlefield,” but they have nothing to do with war. They’re Tom Clancy novels, at best, stories with huge, meatheaded plots, mixed with multiplayer modes that have evolved into esports. It’s not even fair to call these games abstractions of reality.

This War of Mine, however, is fairly called an abstraction of reality, even if it weaves the tale of civilian survivors of war into what is distinctly a game. And that’s precisely why I hated playing This War of Mine, because it felt unfair. I don’t play video games to lose. Even if a game is painfully difficult like a roguelike (defined as a game with procedurally generated levels and permadeath), I know that winning is still a possibility. That’s what keeps me playing.

I got through three games of This War of Mine before I decided to put it down. This being the season for the usual, fall rush of big budget triple-A blockbuster video games, there are too many other games designed purely for entertainment that I can play right now, to warrant spending my time on a game that is deliberately frustrating and hopeless.

Therein, with some honest introspection, also lies the meaning of This War of Mine. It’s a privilege that I can think this way, and can push the brutal lessons of This War of Mine out of my mind to go enjoy Call of Duty: Advanced Warfare, if I want to. Pearl Harbor and the attack on the Twin Towers were devastating assaults. The last time the United States saw anything even remotely like the protracted siege and long-term civilian suffering depicted in This War of Mine, however, was during the American Civil War which ended almost 150 years ago. The civilian experience of war is alien to my reality, something I only see on the news, and can likewise choose to ignore whenever I please.

I felt indicted and didn’t mind. This War of Mine tries to give us the barest taste of what it might be like to be trapped behind the lines of a war, with our entire world crumbling all around us. If that feels uncomfortable, if it is no fun whatsoever, the developers have accomplished precisely what they intended to.

The splash screen includes a link to make a donation to War Child International, a group of charities that seek to help children and young people who are the victims of armed conflict. This is why it’s worth allowing ourselves to be shocked out of our complacency by a game like This War of Mine. It reminds us that some people can’t just switch off a computer monitor, and walk away.

Disclosure: Our review copy of This War of Mine on Steam was provided courtesy of 11 Bit Studios.

All images via 11 Bit Studios