The mythological and musical comic collaborations between Kieron Gillen and Jamie McKelvie will suck you in about as quickly as a killer song hook.

With the backdrop of the comic book world behind them, they and longtime collaborator and colorist Matt Wilson have been transforming everything we know about what makes a successful comic. Their work, ranging from the ongoing Britpop Phonogram, the queer and progressive Young Avengers at Marvel, and now Image Comics’ rock ‘n’ roll demigod ballad The Wicked + the Divine, has ensnared fans, and just like any encore, they want more.

Lucky for them, The Wicked + the Divine—affectionately referred to as WicDiv by fans—is already in the early stages of being turned into a TV show. All the world’s a stage, but for these dynamic characters it’s a particularly brief one. The demigods are reincarnated every 90 years, but they get just two years to live as icons. During that time, every stage invites a battle among musical immortals as they fight for the adoration of fans.

The demigods are from all walks of life, each with their own set of complexities—and the basis for the gods isn’t solely Eurocentric. Race, gender, and sexuality are only a small part of what makes these characters tick; the protagonist is a biracial 17-year-old girl from London.

But what really drives them are the bigger mysteries in the series, kickstarted by a rock show, a genderbent Lucifer, and some rather peculiar deaths. Why them? Who is trying to kill them? Can any of them really beat fate? And can they pull off that killer show?

We recently talked with Gillen and McKelvie about what goes into making the pages pop, who should get credit on a comic book, and why they’re uncomfortable with the idea of being complimented for adding diversity to their books.

I recently picked up The Wicked + The Divine trade volumes, and one thing that struck me was just how vibrant and colorful they are. How intentional was that going into the look and feel of it?

Jamie McKelvie: Very. We’ve given a lot of thought to every single aspect of the comic. Probably more thought than we should.

Kieron Gillen: It’s a logical extension of our previous work. We work with Matt [Wilson], the colorist, who unfortunately couldn’t be here because he’s off signing Paper Girls. What we did in Young Avengers and trying to take it up to a next level—that sounds like a terrible thing to say—but it was very much like, “OK, we’re battle storytellers, what can we do next with it?” The god effects and—

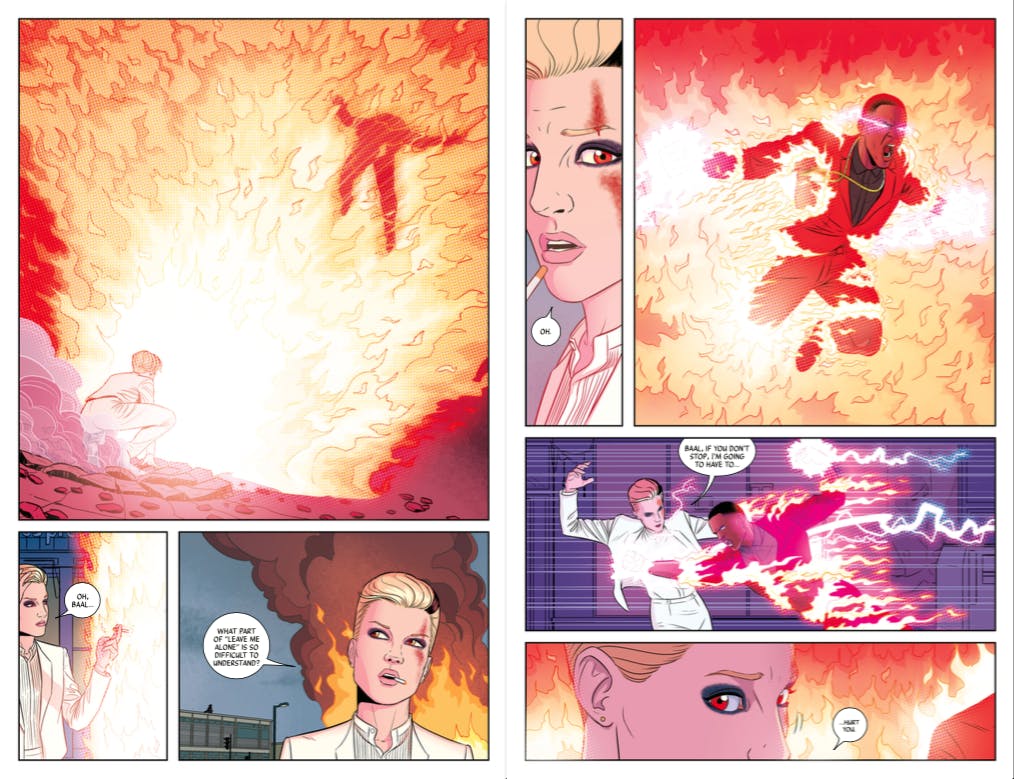

JM: When you’ve got the fights between the gods you also treat it as if it was a gig, so the way the coloring was done like that. But every single aspect of it is planned, all the way through, from even just the conversation pages.

KG: Like when Luci[fer] uses her powers in the first scene, it’s like she’s in spotlights. And the gods are in spotlights when they choose to do miracles. Anytime you have a fight scene it’s on stage. Especially early on, me and Matt are saying, “More, More!” [You] lose all subtlety.

And then you’ve got stuff like Issue 8, if you’ve seen, good old Dionysius, when we’re doing the rave club episode.

The 1-2-3-4 setup.

JM: Which is a lot of work for Matt because it’s essentially rethinking how it works entirely. Normally he can color a book in four days or so, and it took him maybe three days to figure out how he’s gonna do this.

KG: Normally there’s a palette, if you’re literally walking on every page. There are definitely issues where the colorist is the lead singer, if you take our usually crappy metaphor. The growth of colorists’ importance in comics and getting credit for what they do, I think, is one of the big trends over the last few years, so we’ve definitely tried to both embrace that and push it as hard as we can … There’s definitely stages where people want to know the concept of credit. And most of the noughties [’00s] were a writer-dominated period. It’s the independence ringing from the ’90s being also dominated by the superhero medium.

JM: It depends what pub you’re looking at.

KG: We credit our Flatter. The Flatter is the person who prepares the pages before the colorist goes in. And not many books credit their Flatter or their colorists. So the question of who should get credit is on everybody’s minds, I think. And since it’s our book, why not?

Do you think it’s gotten better in recent years?

KG: [jokes] Thanks to our efforts, yes.

JM: It has, it has. We still have a long way to go because a lot of people just don’t realize what a colorist does, and it’s fair enough because if you don’t have the background you might not realize. We were like, what should we call him? Well, he’s a Flatter, so we should call him a Flatter.

KG: I suppose it’s like, if you want the best script for a movie, occasionally a technical term will pop up and that’s fine. People who really want to know about how these things are made will learn the technical terms.

JM: It is changing. You’ve got, even the Marvel and DC stuff now, you’ve got the colorists on the cover. It’s pretty frequent now. But you still, the amount of times we hear “Kieron Gillen’s The Wicked and the Divine.” There’s more people who work on that. It happens within comics criticism as well as outside. It’s more common outside because people don’t necessarily understand.

KG: It’s quite an interesting thing you’ve asked us here. We all fight battles one at a time. I like to think we’re getting somewhere—we as a medium.

WicDiv is a rich and diverse world, both with Laura and many of the demigods, as many publications start to embrace diversity in comics. How have people been reacting to that?

KG: My usual thing is, the problem with most fiction—the major myths we deal with—DC Universe’s main cast were predominantly made in the 1930s while Marvel’s was predominantly made in the 1960s. To use the Baby Boomer metaphor, these people have gotten into position and they’re never moving on—and that level of consolidated cultural power. And you can’t just introduce a character into the DC Universe who’s the most powerful person on the planet and make it a trans man because that job’s already taken by Superman. In a fictional universe jobs are filled. There’s only one Gandalf, there’s only one Sherlock Holmes, and you can’t duplicate them. You have to find a different niche.

And so when you make a book in 2014, we make a book that feels like 2014. And if it’s in London, it feels like London. So it was like because we can, and why not? There’s people we know and the world we live in and London. And we put London on the page. This is what 2014 felt like to me.

We’re very uncomfortable with people complimenting us on it because what we do is pretty much the bare minimum. We don’t think we’re anything special in that way. And I don’t think I need to add anything to that; that’s the core of it. It’s sad that we are noticeable. That’s a good way to put it.

We did Young Avengers at Marvel and that was a predominantly queer super team. And we just sort of did it and didn’t really mention it until the last issue because, “Oh yeah,” that kind of thing. It’s that kind of Baby Boomer thought, and Marvel are very aware of that. They’re conscious and they’re aware.

Do you have any updates on the TV adaptation of WicDiv?

JM: Nothing we can talk about.

KG: We’re still trying to find the right people and talking.

JM: Putting everything together, basically.

KG: As a show, there are certain things, you know, to do it. There’s certain places it won’t fit and certain places it does fit. Worrying about a lot of things can be kind of pointless.

What can you tease about upcoming issues?

KG: Commercial Suicide [Vol. 3] is basically an arc of guest artists, so basically there are five guest artists, whose work is outstanding. There’s one issue of that, which is a remix issue, which has just come out. The idea is that we took all of the previous 13 issues and cut them apart and rewrote them to tell each story with whole new lettering and coloring so it looks like a whole new comic. It’s the Wōden issue, so it’s like DJ remix culture.

So that whole arc is weird and sad, and obviously after what happened in Issue 11 it’s a shadow over all that. It’s a pretty grim and introspective arc, and we get a lot of meat from the gods. And the fourth arc, whose title I haven’t revealed—the name hasn’t been quite decided—is gonna be the rock ‘n’ roll and pop album arc.

JM: It’s exciting. I’m looking forward to it because that’s when I come back onto art. [First] is Stephanie Hans’s Amaterasu issue, and then it’s Leila Del Duca’s Morrigan issue, and then Brandon Graham’s doing a Sakhmet issue. And then I come back on Issue 18. I’m very excited.

THE WICKED + THE DIVINE will feature variant cover by @leiladelduca http://t.co/iLnQ3BbnD9 pic.twitter.com/aglKXR3YDX

— Image Comics (@ImageComics) October 14, 2015

KG: The fourth arc is like—do you know like the fifth issue? A lot of the fourth arc is like the fifth issue. The action sequence of Luci’s breakout, there’s quite a lot of action in that arc. The end of the year is the end of a big state. It’s kind of the end of a trade tends to be big beats.

And the fifth and sixth volumes, when we go into Year Three, involve more kissing. The main thing I’m worried about in the third year is, is there too much lesbian kissing in this arc? But there’s not enough men kissing; that’s actually a problem. So is that like, should be there more kissing all-around? I’m not going to reduce the amount of lesbian kissing, but maybe I’d add more kissing. [jokes] Writing is really hard.

What other styles of music do you want to be able to portray on stage in the comics?

KG: We’re doing a bit of the Sakhmet gig in the Sakhmet issue. But a lot of it the gods are kinda like, we definitely need some more ballads at some point. But what the gods do isn’t really music. It’s evoking music but it isn’t music, per se. What’s more interesting is when we go, I wanna do—

JM: We’re doing the historical issues, yeah.

KG: We’re going to do the romantic poets, which is like, there’s an 1830s issue, which’ll probably come after the end of the fourth arc.

That’s the cycle before the beginning of the series, right?

The 1920s, the 1830s, so two back. And eventually we’ll go back to the 1920s as well. So ancient Rome, there’s one I’m doing there. There’s one really far back in the pre-historics, and a couple more I’m playing with. I kinda want to do a Japanese one and another set in South America, but that’s kind of tentative. That’s more like the different ways it could be. There’s some fun stuff planned.

I’ve read it a couple times now, and there are things I caught the second time that I completely missed the first time around.

JM: Well, it’s designed to be reread—and to be reread maybe even at the end of each arc. Go back to the previous stuff to see what it reveals about the previous stuff.

KG: It’s a book about cycles, and the fact that the ends of the first and second arcs perfectly mirror each other. Sort of the idea that we’re repeating. “Once again, we return,” as we say all the time.

Watchmen was my way into comics, and so Watchmen is a book designed to be reread. It’s like a pop record. With WicDiv, we kinda like the idea that people come back and hopefully get something when they reread because it’s, “Oh yeah, that bit references this bit.” Hopefully that is the plan. We don’t make it easy for people despite appearing quite pop.

Photo via The Wicked and the Divine/Image Comics