Calling the recent boom in digital technology, artificial intelligence, robotics, and biotechnology the “fourth industrial revolution,” the World Economic Forum, determined that by 2020—just a few years from now—as many as 7.1 million jobs may be lost in the world’s richest countries through redundancy and automation.

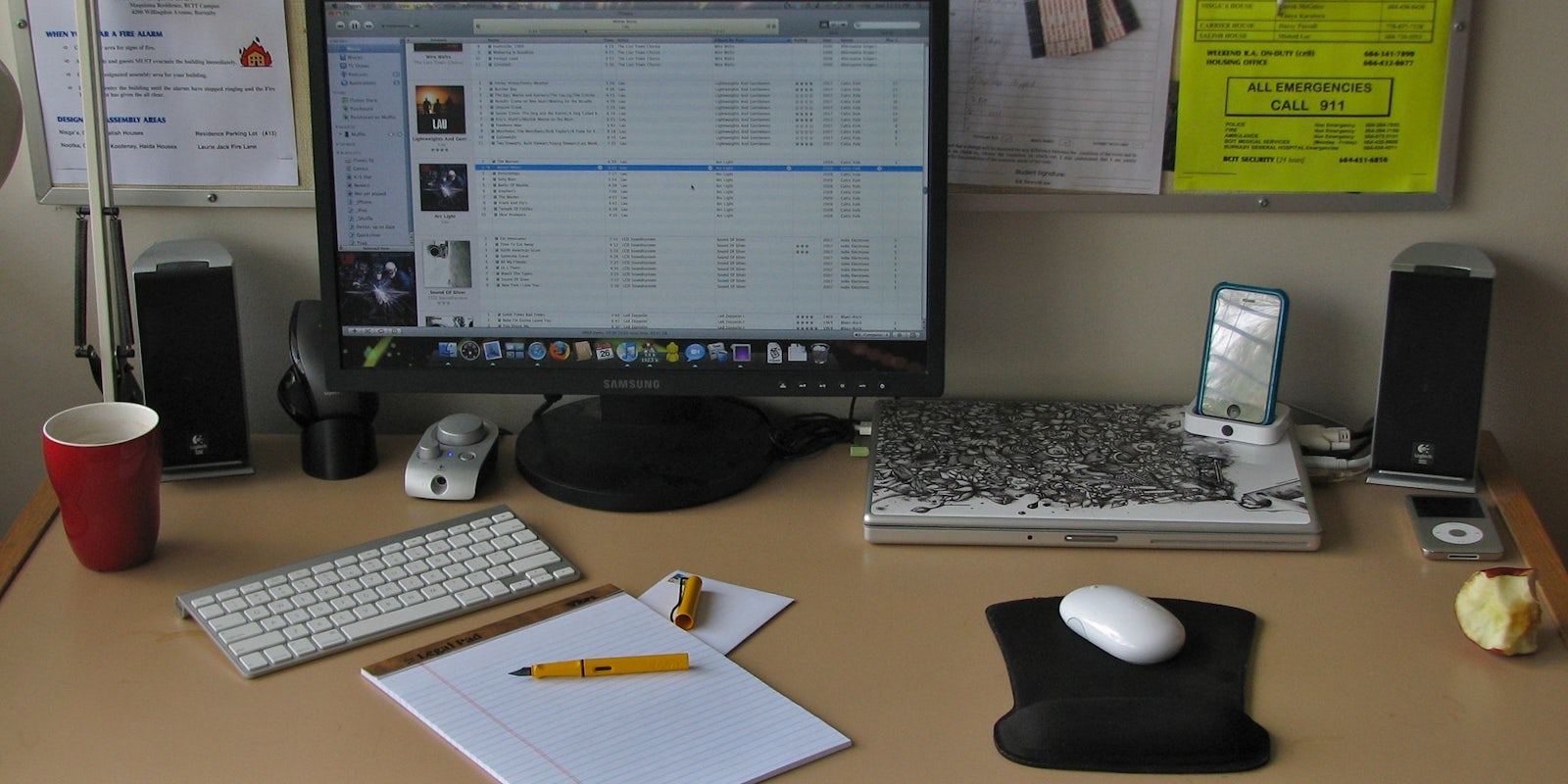

In particular, the forum, which is meeting this week in Davos, projected that administrative and white collar office jobs would be hard-struck by a major outburst of technological development. Though this could be offset by the creation of 2.1 million positions in fields like technology, media, and professional services.

In other words, if you’re a millennial or Generation Xer who is worried about maintaining steady employment in your future, you should be paying attention.

This dire warning calls to mind a favorite historical anecdote of mine from the ancient Roman Empire.

We as a society need to start asking ourselves tough questions about the nature of the technological progress we are witnessing and what it means for our future.

In the aftermath of the great fire in 64 AD that destroyed large sections of the city of Rome, Emperor Vespasian began a large scale public works project that employed thousands of Romans by having them construct new buildings, roads, aqueducts, and other forms of infrastructure. One day, as the population labored at these various endeavors, an inventor approached Vespasian and asked if he would be interested in bankrolling a special machine that would allow him to rebuild the city more quickly, cheaply, and efficiently than ever before. Instead of accepting this offer, Vespasian observed that “my people need jobs” and continued with the less efficient—but, arguably, more humane—civic construction program.

Flash forward nearly two millennia and we have repeatedly faced the same choice that confronted Vespasian.

“After farms were mechanized, Americans moved to factories,” explained former Labor Secretary Robert Reich in an op-ed for Marketplace on Wednesday. “After manufacturing declined—in part due to technologies that dramatically cut the cost of shipping goods—we moved into services.” Corporate strategic advisor Irving Wladawsky-Berger made a similar point in a Wall Street Journal op-ed last November.

“Nothing illustrates the impact of technology on jobs like the dramatic decline in the U.S. workforce employed in agriculture—from 41 percent of the population in 1900 to 2 percent in 2000,” he wrote. “Big declines also occurred in a number of other occupations. Automobiles reduced the demand for blacksmiths and stable hands; machines replaced many manual jobs in construction and factories; and computers displaced a large number of record keeping and office positions.”

Fortunately, there are steps that nations can take to prevent the mass displacement of millions of their workers. According to the World Economic Forum’s report, investing in education and adult learning programs can retrain workers whose current fields of employment may be reduced or outright eliminated by future advances in technology. Similarly, because roughly 65 percent of children starting primary school today will work in jobs that currently don’t exist, it is necessary for our education system to train children to be adaptable and innovative learners. Finally, as Klaus Schwab, the founder and chairman of the World Economic Forum, put it, nations need to prioritize avoiding the worst case scenario of “talent shortages, mass unemployment, and growing inequality” that will result if technological advances are allowed to bypass the human factor.

When all is said and done, the machines that we create and knowledge that we use in order to create them must always be the servants of mankind rather than our masters.

Beyond education and retraining, we also need to embrace the various ways new technology can alleviate economic hardship as well as cause it.

“As someone who works at the nexus of technology and social change, I’m far more encouraged by the promise of the Fourth Industrial Revolution to alleviate human suffering than discouraged by its risks,” writes Ryan Scott, founder and CEO of Causecast, in a recent Huffington Post article responding to the Davos report. He cites as one example The Social Collective: “A digital tool that provides monitoring and evaluation so that nonprofits can understand the personal and professional development of individuals and analyze their employability. It also enables donors, policymakers and the private sector to track skills development and shape the details around the needs of job creation for given regions and countries.”

On a deeper level, though, we as a society need to start asking ourselves tough questions about the nature of the technological progress we are witnessing and what it means for our future. The Vespasianic approach—namely, to outright suppress technological innovation as a way of protecting jobs—is neither practical nor desirable in our globalized economy. At the same time, considering that technological unemployment has been a major problem since the dawning of the Industrial Revolution, it’s morally irresponsible to simply allow it to wreak havoc on people’s lives without any kind of check or regulation.

Writing about the history of how scholars and pundits in the past have made predictions regarding technological unemployment, Rebecca J. Rosen of the Atlantic notes that “this history is much more valuable than some pat lesson about the foolhardiness of prognosticators. Even for those who were right, the fact that they saw the future accurately mattered very little, as no one could have known they were right at the time. What matters, then, isn’t whether early observers were right or wrong about the long term, but whether they were sufficiently empathetic in the short term.”

This, ultimately, is the bottom line. When all is said and done, the machines that we create and knowledge that we use in order to create them must always be the servants of mankind rather than our masters. Even if certain technological developments are beneficial in the long-run, it is essential that we minimize their harmful effects on workers who might be displaced in the short term. By failing to take these necessary steps, we aren’t simply neglecting the vulnerable and powerless in our society, but committing a serious error in our greater thinking.

If we allow the welfare of individual human beings to be sacrificed in the name of progress, we reveal that we’ve forgotten what the term “progress” is really supposed to be about.

Matthew Rozsa is a Ph.D. student in history at Lehigh University and a political columnist. His editorials have been published on Salon, the Good Men Project, Mic, and MSNBC. Follow him on Twitter @MatthewRozsa.

Image via Hugo Chisholm / Flickr (CC 2.0)