Seth Sivak sounds perfectly calm as he tries to figure out why Streamline, the most important video game his company has ever developed, isn’t working.

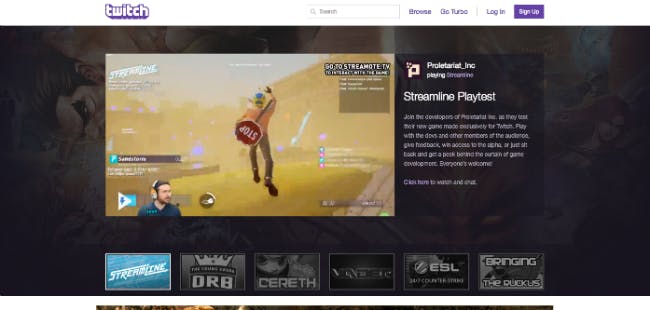

Streamline could revolutionize the way games are played on Twitch, the most popular streaming platform in the video game world. But first, Sivak needs to convince the most popular Twitch broadcasters—the burgeoning rock stars of video games—that Streamline is worth playing. And that could be difficult if Sivak can’t get the game to work during this live Twitch broadcast as 1,500 people watch from their home computers.

Hours earlier Sivak, CEO of Proletariat Games, towered over his standing desk in a heavily trafficked corner of Proletariat’s office in downtown Boston. Behind him, a room full of a dozen game developers and producers seated at desks and standing in front of stacked flat-screen monitors raucously put Streamline through its paces. It’s a third-person action game that operates in a small arena. A broadcaster hosts a match and plays as a hunter wielding a giant Stop sign. And here’s where Streamline breaks the model upon which Twitch has built its streaming empire: Instead of letting the audience merely observe, broadcasters can invite up to 15 viewers to play with them, as runners in the game.

The players scramble around the arena picking up orbs to score points, like Pac-Man in the classic arcade game. Meanwhile, the hunter tries to tag out the runners by swatting them down with the Stop sign. If the hunter tags all of the runners out before the clock runs out, the hunter wins. Otherwise, the runner with the most points when the clock runs out is the winner.

Sivak tells me that on more than one occasion the developers at Harmonix, makers of the Rockband games and Proletariat’s office neighbors, have complained about the noise barreling out of their space during these playtests. Streamline is a frenetic game that tends to get the blood pumping. But even with the cacophony of his developers playing the game behind him and the foot traffic through the hallway next to him, Sivak’s eyes remained locked on the chat window on Proletariat’s Twitch channel, looking for feedback from players.

Later, I pull up a Twitch channel run by Joseph “Swiftor” Alminawi to watch the live playtest the Proletariat team spent the day preparing for. Alminawi has more than 900,000 followers and is one of the top 20 broadcasters on Twitch, making this Streamline’s largest playtest yet. The minutes tick by as Sivak and his team at Proletariat try to help Alminawi add viewers to the game.

While only 15 runners can be invited into the game, the whole Streamline audience is given at regular intervals different rules they can impose on the players, like making them move in slow motion, switching on low gravity, taking away the hunter’s ability to smash the runners, or turning the floor of the arena into lava. The viewers vote to decide which of these changes is activated.

“The biggest thing there for us was moving viewer interaction out of chat,” Sivak says. “You’re so limited if you’re just doing chat commands. And chat is supposed to be a social community space for that channel. You don’t want to make broadcasters sacrifice that to play our game. That’s where the viewer [rules] controller came in, and that’s where bingo came from.”

Every Streamline viewer has an individual, unique bingo card where each square is a game condition. For example, the broadcaster getting a double kill or a game rule being changed can represent a square. The viewer has to click on the corresponding square on their bingo card when the condition is met.

“It’s a mini game that’s still relevant to watching, but it’s like a shared experience because you’re all watching this together,” Sivak says. “It’s like if you’re playing Oscars bingo.”

Viewers can also bet on which runner they think will score the most points before the clock runs out and the match ends, or whether they think the hunter will tag all the runners out. All of this takes place on the game’s adjacent streamote.tv website, where the interactive functions are embedded.

But no one is on the streamote site during the playtest, because the chat window there isn’t working. Instead, everyone is on Alminawi’s Twitch channel, trying to follow a maddening stream of comments streaking through the chat window.

Players are asking what the hell this game Streamline is, and what happened to Grand Theft Auto V (the game Alminawi had previously been streaming), and occasionally throwing insults at Alminawi while Proletariat’s community management team tries to keep up with the flood of questions and provide support.

Finally, “We got someone in!” Sivak says excitedly over voice chat. “We got one person in,” Alminawi says, on his camera feed that’s laid over Streamline’s start screen.

“Thanks for your patience, guys. It’s my first time doing this,” Alminawi tells his audience. “We’re going to work it out, and we’re going to have some fun. It’ll be a very cool experience, I promise.”

Streamline is one of three viewer-participation games in development as part of the Twitch Developer Success program announced in March at the Game Developers Conference in San Francisco. The program promotes a new philosophy of game development called Stream First, a term Twitch credits Proletariat with coining.

The other two interactive games, Superfight and Wastelanders, are card and strategy games, respectively, very different from the kinesthetic action of Streamline. But these aren’t Twitch’s first or only foray into audience-participation gameplay.

The phenomena began with Salty Bet, a game that combines a Twitch broadcast with an online betting service. The broadcast features AI-controlled fighting game matches with bizarre pairs of opponents that don’t necessarily hail from Street Fighter or Mortal Kombat. Salty Bet uses a freeware fighting game engine called M.U.G.E.N. that gamers use to create custom fighters. Viewers can also log into the Salty Bet website and place bets on the matches using a fake currency called Salty Bucks.

Twitch Plays Pokémon—Twitch’s best known and least organized group play experiment—is a betting channel similar to Salty Bet. Back when the channel was first created in 2014, Twitch Plays Pokémon was a series of emulated Pokémon games being streamed to the channel that viewers could then control via text-based commands.

Viewers could type in chat commands like “up,” “down”, “a,” and “b,” which corresponded with the buttons on the original Pokémon game hardware. The Twitch Plays Pokémon channel would then read those commands and process the input back into the game.

It was, predictably, a chaotic mess, yet viewers managed collectively over time to beat almost a dozen different Pokémon games. Perhaps because the franchise was so recognizable, the Twitch Plays Pokémon experiment caught the attention of the press. It became clear it was possible to play games on Twitch instead of merely watching them.

After a rocky start to Proletariat’s playtest with Alminawi, the team wrestles the technical issues into submission and the trial run gets going in earnest. For an hour and 40 minutes, Alminawi and his audience have a great time with Streamline. They play through both of Streamline’s maps, rotate in some new players, and get the hang of the mechanics.

Something slowly begins to change once the playtest begins in earnest. The community managers from Proletariat cease feeling like technical support and instead feel like just part of the crowd, chatting with the viewers and having a good time. Sivak’s voice is more relaxed. He’s laughing along with Alminawi. The social aspect of Streamline, the game’s most sparkling point of appeal, is shining through.

“That’s where I think the real magic for Streamline comes in,” Sivak told me earlier that day at the Proletariat offices. “This is why the playtests live, public playtests are so important, is that when you have a community member who is in the game with the broadcaster, who’s effectively a celebrity to them, and they’re playing in front of an audience of people they really care about and identify with, it’s a super interesting experience.

“We’re all playing and laughing and commentating and taking part in this big, shared entertainment experience.” Sivak continued, “so that’s why [it] works, and why broadcasters want it.”

I spoke again with Alminawi after the playtest, to see how things went from his perspective. After all, Streamline has explicitly been designed in part as a tool to help him and other broadcasters grow their audience and their channels on Twitch. His assessment is ultimately the most important.

“I liked that a lot of the interactivity was just automatically taken care of,” Alminawi said. “The bets, the bingo, the player behavior modifications (slowing down, etc.). Generally, all of this stuff requires a TON of cooperation, trust, and patience from the players participating. Having the actual game handle all that lets me focus on the really fun stuff.

“As far as what I didn’t like,” Alminawi added, “my biggest gripe was perhaps the verticality in the game. There’s a lot of motion and jumping, and I feel that makes it difficult for people watching the show to understand what’s going on. This is a very solvable thing, in my opinion.”

Even assuming that Sivak and Proletariat make Streamline as smooth an experience for broadcasters as possible, there’s still the question of financial viability. Twitch users will have to actually purchase copies of Streamline to play with their favorite broadcasters. Will they be dazzled enough to make that investment? Or will they be content to merely watch games and take advantage of the interactive features like betting, bingo, and voting on rules changes?

Anyone who buys the game can also broadcast it on their own Twitch channel and play as the hunter. But will they?

“For someone that wants to get into broadcasting, Streamline offers a robust tool set for viewer interaction and is structured to make it easy to create great content,” Sivak said. It’s the best answer he can give, because there really is nothing else quite like Streamline. For now.