As we all know, the Internet has shifted the polarity of the media world. Newspapers all over the country continue to close down, and many respected journalists and writers have flocked in droves to the very online publications that put them out of jobs.

And yet a cultural tension still persists between online writing and “real” writing in print. Bloggers and online journalists have been thought at various times to lack the legitimacy of “real” journalists who write for print publications. And by the same token, many writers who established their reputations in print seem not to always understand Internet culture (cough Jonathan Franzen cough). This disparity surfaces often and, sometimes, in unexpected ways.

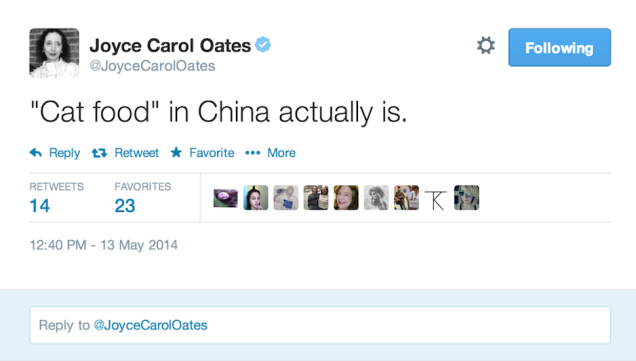

A writer who seems to have taken up permanent residence in the gulf between “real” and online writing is Joyce Carol Oates. Gawker recently published an article titled “An Open Letter to Joyce Carol Oates: Delete Your Twitter.” In the article, writer Michelle Dean references a casually racist tweet from Oates’s Twitter feed.

Screengrab via Gawker

Like the title of the article suggests, Dean concludes that Oates should shut down her Twitter and focus on books. The Internet is too complex an animal for Oates to understand, and she should stick to the relatively simple rules of “real” writing. Dean makes one very good point about writers and their Twitter accounts. Addressing Oates directly—it is an “open letter” after all—she says:

Expertise in one form of writing does not necessarily mean mastery of them all. When it comes to writing long books, formulated in multiple pages and paragraphs, every sentence read in context with the one preceding it, you are pretty good at that, better than most of us can ever hope to be. But when you offer disconnected, abbreviated, context-free thoughts… you are not so good.

Stephen King, another “real” writer who came late to the Internet, got in hot water when he opined on his Twitter about the Woody Allen controversy, referring to Dylan Farrow’s New York Times missive as “bitchery.” King quickly issued an apology, saying he “was still learning” about Twitter. But his mistake begs the question: What could such a prolific writer of prose have to learn from a social network?

It’s interesting that both Oates and King are famous for being prolific. One wonders whether the immediacy of Twitter both attracted their attention and “taught” them to apply a filter where they usually have none.

The disparity between “real” writing and the sort that happens on the Internet is perhaps nowhere more apparent than in the recent movement of “trigger warnings” from the Internet to college literature classes.

Trigger warnings were initially used to warn members of online forums that the subject of discussion could “trigger” strong emotional response from victims of trauma. People suffering from PTSD can re-experience trauma long after the traumatic event is over, sometimes cued by certain words. So in threads where sensitive topics were discussed, the warning “TRIGGER ALERT” would be printed in large letters at the top of the thread to warn off those who might be adversely affected.

But as trigger warnings made their way to the Internet at large, their initial usefulness became somewhat watered down. Internet writers began to include trigger warnings in all manner of articles, and some, notably Susannah Breslin, began to question their legitimacy. Then a resolution was passed at UC Santa Barbara to attach such warnings to the syllabi in classes where works of literature, such as Beloved and even The Great Gatsby, are taught. The measure sparked a strong backlash from the online community.

The breathless, hand-wringing cry of “Is nothing sacred?” that has sounded across the digital landscape since the Internet first started eating the world finally has an answer. Journalism? Not sacred. Mom-and-pop retail stores? Nope. Personal privacy? Hell no. Works of great literature? HOW DARE YOU.

Some of the tension between Internet writing and so-called “real” writing can be attributed to how different media yield different kinds of authorial identity. Most informed readers of “real” books understand that words in the text are not necessarily those of the writer but of a constructed persona. Even the work of someone like Joan Didion, who ostensibly writes from a personal point of view, isn’t meant to be read as coming from the same Joan Didion who likes her coffee a certain way and lives at such and such an address. The narrator of Slouching Toward Bethlehem is not Joan Didion but “Joan Didion,” a character that the writer created.

But for whatever reason, people understand Twitter feeds to represent a much truer authorial self. Twitter accounts aren’t authors’ personas but naked identities. Thus Joyce Carol Oates’s racist tweets come across less like how Oates herself probably understands them, as a complicated stylization of her own opinion filtered through the formal strictures of 140 characters, and more like a tape recording of Donald Sterling.

The Internet community generally polices its content in a much more direct way than the literary community does, if for no other reason than the barriers to publishing are much less involved. When you can publish something at the push of a button, keeping the community free of racism and overt expressions of privilege requires a heavy hand. Meanwhile, the cult of print authorship highlights the individual’s perspective more than that of the online community at large, and allows itself much more leeway in constructing nuanced discussions of race and hierarchies of legitimacy.

So do writers who have become used to getting the benefit of the doubt in print hurt themselves by opening up online? Does the Internet provide too easy a mouthpiece to their otherwise more considered writerly voices? The old adage “write drunk, edit sober” doesn’t seem to leave much room for Twitter, where the least of your ideas are instantly broadcast to the masses.

Maybe Dean’s article about whether or not Joyce Carol Oates should close her Twitter doesn’t go far enough. Maybe all “real” writers should stay offline.

Or maybe, like Stephen King, writers who have established themselves in the real world should have to take a short tutorial on what works online and what doesn’t. (I’m imagining a webinar taught by George Takei for some reason.)

Twitter should be a great place for writers. It’s the most word-centric of the social networks, putting a premium on economy of language. And where YouTube and Wikipedia usually lead to time-sucking K-holes, in my experience, Twitter visits tend to stay short. Popping off a few easy Twitter jokes can even get the creative juices flowing.

And yet it’s extremely uncommon to see an author’s Twitter demonstrably add to his or her “real” body of work. In fact, there are exactly two writers of note that I can think of at the moment that acknowledge the formal strictures of Twitter while still maintaining a unity of voice with their other “real” work: @Mat_Johnson and @JoyceCarolOates.

Photo via Spokane Focus/Flickr (CC BY 2.0) | remix by Jason Reed