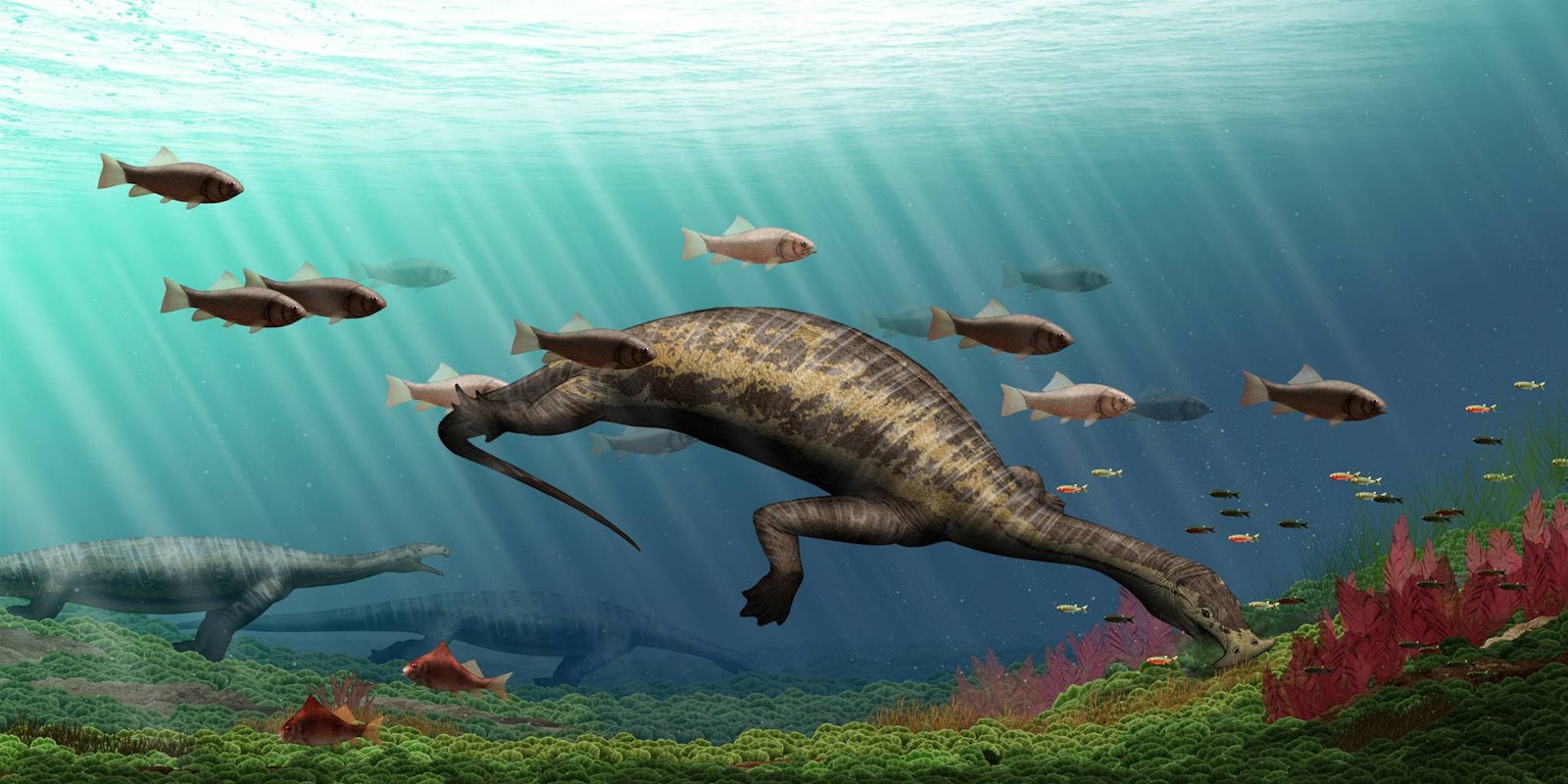

A newly discovered fossil of reptile hailing from the middle Triassic period reveals a very unusual hammerhead-shaped jaw—completely dismantling the way researchers thought the ancient creature lived.

First described in 2014, researchers thought the crocodile-sized Atopodentatus unicus (whose name means “unique strangely toothed”), had a downturned snout shaped like a flamingo’s beak. And boy, was it weird looking. According to that report, Atopodentatus used its strange jaw to stir up small crustaceans and other little critters from the soft mud of the sea floor. But researchers discovered a new fossil in Southern China that was better preserved and revealed an even stranger jaw that harkens to the hammerhead shark. They published a new description of the ancient reptile in the open access journal Science Advances.

This reptile is the first of its kind, Olivier Rieppel, a paleontologist at the Field Museum in Chicago, and one of the paper’s authors told the Daily Dot in a phone interview. The original fossil was very poorly preserved with its skull bones separated from one another.

“Only when the new specimen came up, you saw this hammerhead,” Rieppel said. “No one [looking at the original specimen] would have expected the reptile to be so strangely built.”

But the new specimen was in much better shape—albeit a little flat.

“The reptile was very compressed during fossilization,” Rieppel said. “The skull was compressed dorsoventrally—it was flattened—but everything stayed in place. The contours of the skull are immediately obvious.”

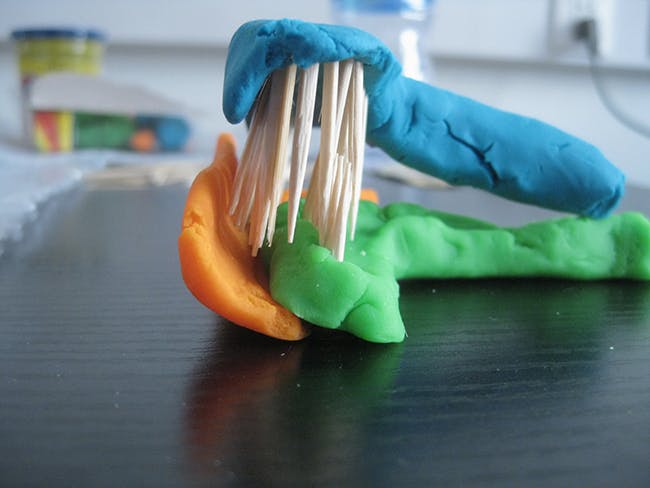

Rieppel specializes in working with flattened reptiles, reconstructing them through 3-D modeling using very advanced materials—like Playdough and toothpicks.

Rieppel and his modeled the clay after the bones of the flattened skull, using toothpicks as a stand-in for the creature’s peg-like teeth. They think Atopodentatus used its unique jaw to scrape up algae from rocks and then pushed water back out its sieve-like teeth—similar to how blue whales filter tiny krill from huge gulps of sea water.

The jaw isn’t the only thing that makes Atopodentatus unique. Now that researchers think it was exclusively into eating plants instead of munching on tiny animals, that makes it the oldest known herbivorous marine reptile. Reptiles are not often plant-eaters, Rieppel said, because of the way reptile skulls are built. Their skulls have moving parts, which make them really good at eating insects. In order to become good plant-eaters, those moving parts need to fuse together.

“One of the things that makes this important scientifically not only the earliest marine herbivorous reptile with a very strange anatomy,” Rieppel said, “it’s also an indication for how fast the marine biota proliferated after the mass extinction at the end of the Permian.”

The Permian extinction event occurred about 252 million years ago and was the largest extinction event in the history of life on Earth. According to National Geographic, the event—for which scientists have no favored explanation—wiped out around 90 percent of the animals and plants on Earth. It hit marine animals particularly hard: Less than 5 percent survived the event. Yet paleontologists are continuously uncovering evidence of a quick recovery—Atopodentatus lived about 242 million years ago.

Rieppel said he couldn’t comment on what this evidence may suggest about current and future extinction events. But he said the current “diversity crisis” in Earth’s living species has inspired a greater scientific interest in studying mass extinction events of the past, so we can model them and understand the conditions that allowed for animals to bounce back—or not.