BY CHRIS OSTERNDORF

Republicans aren’t strangers to social media. But when it comes to Nigeria’s kidnapped schoolgirls, some are questioning the power of Twitter to get things done.

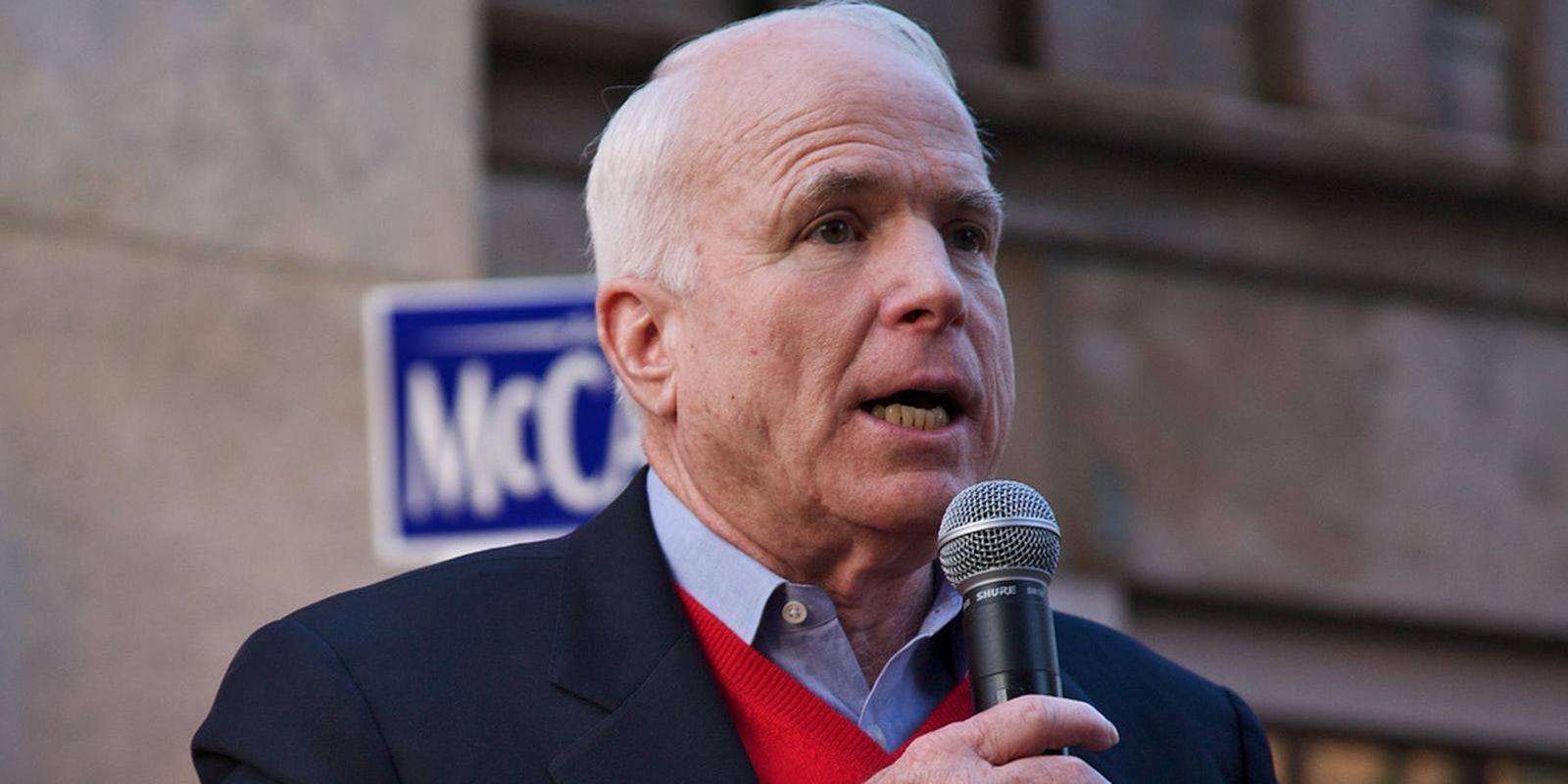

Last week, Politico ran several stories highlighting how even Republicans on different ends of the conservative spectrum, including John McCain and Rush Limbaugh, have become critical of the attention the kidnappings are getting on social media. Numerous celebrities, as well as First Lady Michelle Obama (who has become so invested in the issue she gave the President’s weekly address in lieu of her husband this week), have taken to Twitter, popularizing #BringBackOurGirls and making it the rallying cry for this complex situation.

McCain, however, called for more traditional involvement: military action. So far, White House deputy press secretary Josh Earnest has indicated that any military involvement will be done “in an advisory role.” But Senator McCain doesn’t seem to think this is enough. “We have air and sea and satellite capabilities,” McCain arged. “We have drone capabilities. We should say to the Nigerian government, this is an offense to all human beings. We’re going to act. And we expect you to cooperate with us.”

Meanwhile, Limbaugh described the Twitter movement as a distraction from the United States’ failure to act. On his radio show, the popular and divisive pundit said, “The sad thing here is that the low-information crowd that’s puddling around out there on Twitter is gonna think we’re actually doing something about it. Is that not pathetic? What the hell message does that send?”

Since then, other conservatives have chimed in with their skepticism too. Over the weekend, Fox News contributor and Pulitzer Prize-winning columnist George Will expressed his frustration, saying, “I do not know how adults stand there facing a camera and say, ‘Bring Back Our Girls.’ Are these barbarians in the wilds of Nigeria supposed to check their Twitter accounts and say, ‘Uh-oh Michelle Obama is very cross with us, we better change our behavior?’” Will also went on to say that, “This is not intended to have any effect on the real world.”

Then again, Will’s statement on the hashtag looks positively upbeat compared to Ann Coulter’s, who went so far as to mock it, tweeting herself with a picture reading, “#Bring Back Our Country.”

In a fundamental sense, conservatives are well within their rights to be skeptical of Twitter in the fight to bring back these 300 suffering Nigerian young women. Social media is still a fairly new tool in the fight for social justice, and it’s hard not to get the feeling that the “Bring Back Our Girls” hashtag is very much a result of misplaced Western confusion. Taken to its ugliest, most extreme conclusion, “Bring Back Our Girls” is just a way for Americans to feel invested in something they normally wouldn’t even be aware of, without doing anything to prevent it from happening again in the future.

But this line of thinking isn’t helpful. It’s destructive, and it’s dangerous.

To say that a large part of why people are paying attention to this story comes from Boko Haram’s opposition to Western education is obvious. To say that horrible things go unnoticed in Nigeria and other parts of Africa every day because people in the West don’t have a cultural connection to make is even more obvious. But the problem is that being self-aware of our own shortcomings isn’t enough. Postmodernism may have made us think it is, but acknowledging that there is a problem only takes you halfway to solving it.

Charlotte Alter at Time recently published a piece on how the kidnapped Nigerian girls were mostly ignored by the media, until social media stepped in (she even includes a map showing how the conversation blew up on Twitter.) Furthermore, to say that Nigerians themselves have had nothing to do with the “Bring Back Our Girls” campaign is false. After some dispute, it was revealed that Nigerian attorney Ibrahim Musa Abdullahi originated the slogan. And in the streets of Abuja, chants of “Bring back our girls now and alive!” have been heard in protest.

If social media can make people more aware of the world they live in, then it is doing some good. This is one of Twitter’s best functions, and as always, we should hope that if people become more aware of social injustice this time, they will continue to educate themselves in order to prevent it in the future. It may only be a small piece of the puzzle, but it’s not worth discounting altogether.

Nevertheless, conservative naysayers are entitled to weigh in. It’s easy to see why John McCain would advocate for military action; to look at it as a real, tangible solution in a world that’s become increasingly digital. But just because one might sympathize with McCain’s perspective, doesn’t mean we should forget the complications that military involvement has consistently brought us in the past.

Rush Limbaugh, meanwhile, seems less interested in the situation’s outcome, and more interested in playing partisan politics. Limbaugh has found a way to turn the incident into an indictment of the Obama administration, which is of course what Limbaugh does best. And Ann Coulter has simply decided to keep on trolling, also playing to her strengths.

It is George Will’s sentiment which is ultimately the most troubling. He characterizes Boko Haram as “barbarians in the wilds of Nigeria.” By making their organization seem savage and animalistic, he’s missing the boat entirely. The citizens of Nigeria are people, and deserve to be thought of as such. This includes terrorists. In making our enemies out to be monsters, we forget that it’s people who do the most harm to people.

Chris Osterndorf is a graduate of DePaul University’s Digital Cinema program. He is a contributor at HeaveMedia.com, where he regularly writes about TV and pop culture.