Warning: This article contains massive spoilers for Ready Player One (the novel, not the film).

Parts of the internet are about to tear one another apart over a film that, on the surface, was made especially for them.

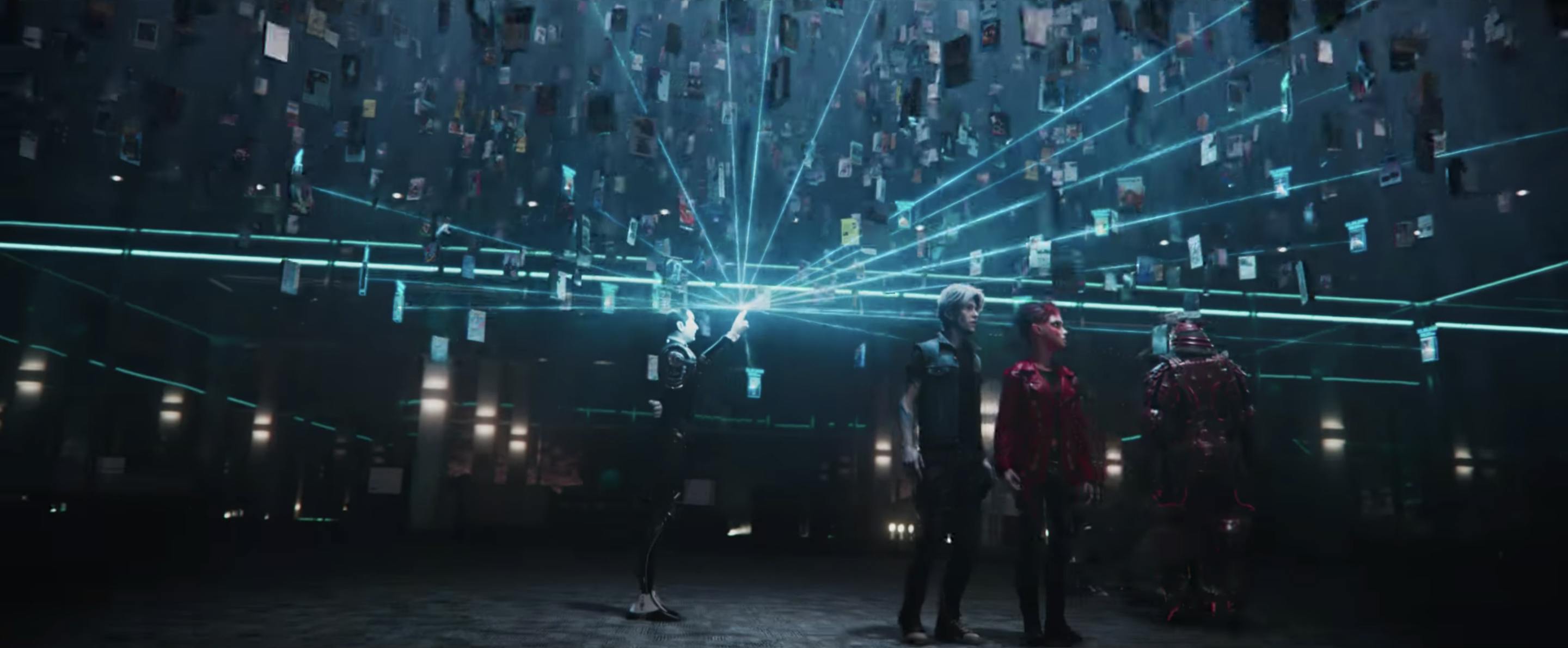

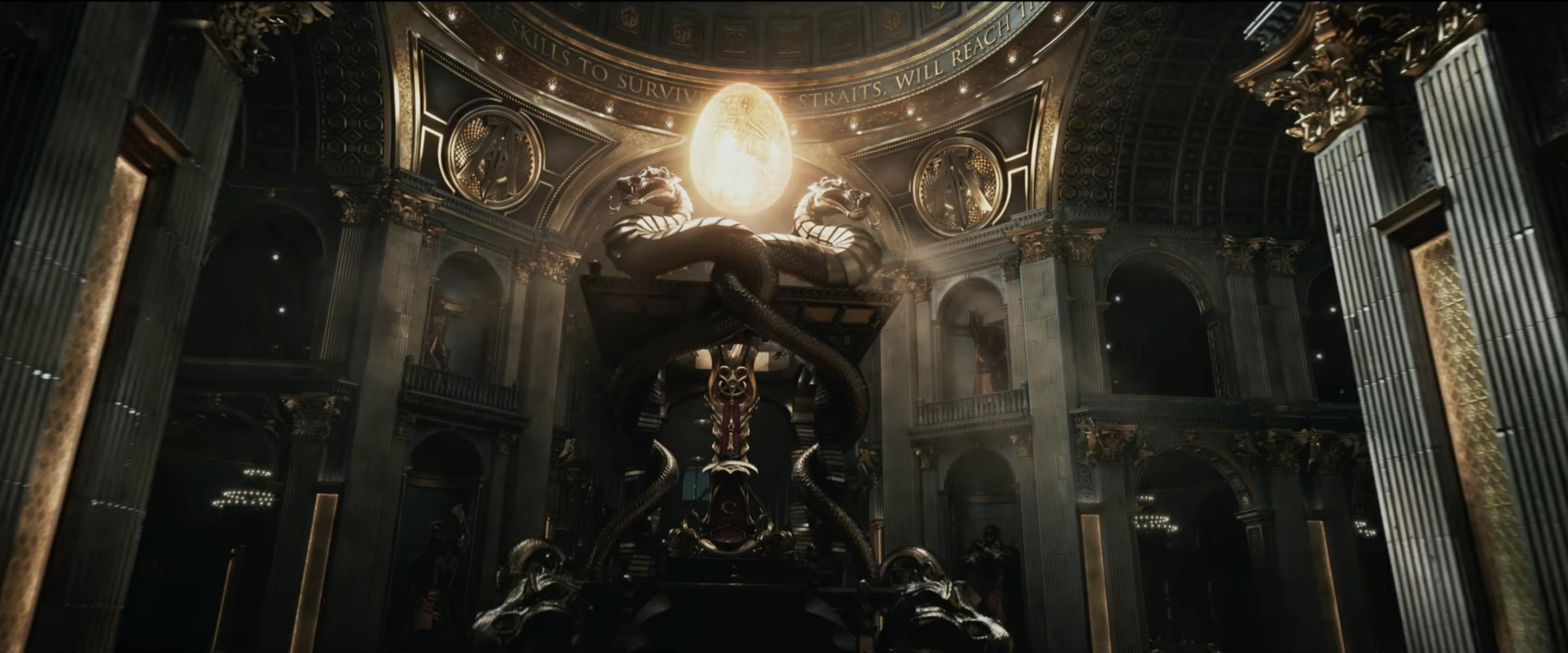

Steven Spielberg’s Ready Player One is a movie adaptation of the 2011 Ernest Cline novel by the same name. The book, best known for its ’80s pop culture nostalgia, is a futuristic story in which young players must compete for control of a virtual reality world called the OASIS to prevent a major corporation from monetizing and corrupting it.

I couldn’t tell you how I discovered Ready Player One. The only reason I know when I purchased it (in 2012, long before I noticed any of the backlash to the book itself) is because the date is captured in my Kindle order history. I sped through the book and remember liking it at the time, but until recently I probably couldn’t recall what happened apart from the broad strokes. It’s like a beach read, something you can pick up on a whim and consume without having to worry about losing your train of thought if interrupted. I think I enjoyed it, but it was forgettable.

But with the film coming out soon, the many criticisms of the book are resurfacing—primarily its treatment of women and obsession with trivia and name-drops over substance. So, I decided to revisit Ready Player One. I wanted to see how it fared now that we’re six years closer to the future that Cline imagined. But after reading it, it’s apparent that much of the book feels rooted in the past.

Ready Player One is entertaining, but the cringe-factor breaks the momentum

Engaging with Ready Player One can be thrilling and exhausting. The pages still fly by once you’re sucked into the story, and yes, there is something kind of cool about seeing those pop-culture references collide, even if most don’t leave anything more than a superficial impression. None of Ready Player One made me want to pick up any of the books, shows, movies, or games it mentions, many of which I had never heard of or missed while distracted by my own ’80s pop culture consumption. But just as soon I got into the story, a flash of secondhand embarrassment would take me out of it again.

There’s a passage from Ready Player One that has repeatedly gone viral, and critics often point to it as a summation of the surface-level essence of the book. You probably know the one, even if you haven’t read Ready Player One.

It takes place almost halfway through the book as Parzival—the username main character Wade Watts goes by in the OASIS—makes his entrance at the birthday party of OASIS co-founder Ogden Morrow. It’s a teenager’s description of all the modifications he made to his new car, but because all of the modifications come from fictional and iconic rides, it becomes more obnoxious by the second.

https://twitter.com/etdragonpunch/status/939927831869407232

This passage is also by far one of the lesser offenders of pop-culture overload. Early in the book, Wade and Aech, his best friend in the OASIS, spend three pages arguing about whether LadyHawke is a good movie. Aech calls it a “chick flick disguised as a sword-and-sorcery picture.” After the history behind the trivia-based challenge to find OASIS creator James Halliday’s world-controlling Easter egg is explained, Wade takes nearly five pages to list just about every movie, TV show, book, video game, comic, and album he’s consumed to prepare. Two of the quests Wade has to complete to find the Easter egg (a common nickname for hidden items) involve him reenacting WarGames and Monty Python and the Holy Grail in the role of major characters.

Hidden beneath the many, many references strung throughout is a message about the dark side of escapism and living your life in virtual reality. Wade sees glimpses of this throughout the book. After he moves to Columbus, Ohio, and assumes another public identity, Wade doesn’t leave his apartment for an entire year in fear that the book’s corporate antagonist will kill him. Wade becomes wealthy enough to afford gadgets galore (including what is essentially a sex doll you can use within the OASIS), but they still leave him feeling empty, lonely, and ashamed. At the end of the hunt, a version of Halliday in the OASIS puts it more plainly: As incredible as the OASIS might be, you should still experience what life has to offer in the real world.

“I created the OASIS because I never felt at home in the real world,” Halliday says to Wade. “I didn’t know how to connect with the people there. I was afraid, for all of my life. Right up until I knew it was ending. That was when I realized, as a terrifying and painful as reality can be, it’s also the only place where you can find true happiness. Because reality is real. Do you understand?”

It’s a fine message to be sure, even if it could be worded a little better. But it arrives after Wade devoted several years to living almost solely in the OASIS and consuming all of Halliday’s interests without pursuing any of his own. Hell, what’s the point of telling someone to live in the real world after you just handed them control of the virtual one?

The OASIS is a fantasy that ignores pretty much every one of its actual problems

At times, Wade Watts is an insufferable narrator. He made it his life’s mission to find Halliday’s Easter egg to escape his poor and miserable life in Oklahoma City. He thinks that becoming the world’s biggest expert on Halliday and ’80s pop culture will get him what he wants, and well, it eventually does. By the end of the book, Wade has inherited the OASIS and Halliday’s entire fortune, which he promised to split with the three other players who helped him get to the end. (He also gets the girl, who ends up being little more than a plot device and motivator for him at times.)

Many of us have probably met a Wade Watts—a gatekeeper who requires people (primarily women) to pass an arbitrary litmus test to be validated a “true fan.” They’re the person who may tell you they support women, but whose actions tend to say otherwise. The person who creepily continues to message a woman when she attempts to cut off contact. The person who refers to women as “females.”

Wade doesn’t change all that much as a character throughout Ready Player One, so by the time he insists to his love interest Art3mis that he’s “a really nice guy, once you get to know me” it’s hard to believe him. And although he’s ready to retaliate against a corporation looking to monetize a free and open OASIS, would he have done the same if someone had suggested a social change? (Given that he happily votes to reelect fictional versions of Cory Doctorow and Wil Wheaton to the OASIS User Council, Wade isn’t too concerned about altering the status quo within the OASIS.)

That attitude extends to his closest friends. In a scene that smacks of transphobia, Wade interrogates Art3mis about whether she’s biologically female after she laments that everyone assumes that she’s a man. (They think a woman couldn’t solve Halliday’s riddles.) Wade also initially views it as a betrayal when he discovers Aech is, in reality, a black lesbian named Helen Harris, who uses a white male avatar because of privileges it grants her. Wade could have grown by exploring those problematic reactions further, but the character (or Ready Player One) isn’t interested in unpacking those ideas.

https://twitter.com/thelindsayellis/status/970019116554866689

Wade never comes to understand that there may have been valid reasons for them kept part of themselves hidden, even without the IOI conglomerate trying to eliminate them. Those fears are real and exist outside of Ready Player One by way of cyberstalking, blackmail, doxing, hacking, sexism, racism, homophobia, and widespread harassment campaigns. Wade’s privilege (and what Aech adopts with her avatar) is real in the OASIS. And while Wade is in the thick of it, he doesn’t engage with any of it; he even naïvely believes that his information is safe in the OASIS until the moments he discovers it isn’t.

We’re already so inundated with nostalgia that Ready Player One feels empty and outdated

Ready Player One was published in 2011, several years before our current reboot renaissance with all of its triumphs and blatant cash grabs. Reboots have taken over TV schedules. Video game manufacturers brought back the systems that defined our childhoods. And as obscure anniversaries roll in for the things we love, studios and companies have attempted to tap the collective zeitgeist and make money off old favorites. (Though fans can almost always smell bullshit.)

Around 30 years ago, being a fan of something or liking geeky things was something that often got mocked or ridiculed. In the kind of pop culture that Halliday (and Wade) revered, they were the underdogs, the heroes in their own stories. Their knowledge saved the day. They gained respect among their peers or at least an understanding. And while the heroes almost always looked like them, they probably never saw themselves in the villain.

In 2018, fandom has long since gone mainstream. Game of Thrones, based on a 20-year-old high fantasy book series, is the most popular TV show in the world. Marvel and Star Wars movies dominate the box office. Harry Potter is a literary staple, one that can still cast a spell in movie theaters and on Broadway. There’s pretty much a Funko for every franchise you can imagine—and the company still releases new figures every month. And that media is finally starting to reflect the fans who’ve always been there as they continue to disprove long-standing myths about who shows up on opening weekend.

And for all of its inventiveness and the endless possibility of the OASIS, it feels restricted on what kinds of pop culture it shows. Early on, Wade Watts listed the authors he read and the directors whose films he watched because Halliday considered them among his favorites. What’s striking about it now is how all of the people Wade mentions are men; the majority of those men are also white. Many of the movies and TV shows Wade watches have white male protagonists. Same with the video games that he plays. Ready Player One does reference abundant media from after the ’80s, but it largely follows the same pattern.

If Halliday’s goal with the contest—apart from bequeathing his entire fortune to one lucky person—is to get everyone as obsessed with the ’80s as he was, then Halliday had an unimaginative vision of it. (It was also the Golden Age of hip-hop, but you won’t find those artists lionized in this book.)

Ready Player One may resolve a number of the book’s larger issues, many of which are more glaring now than they were in 2011. It may find ways to slip some depth and broader resonance into the pop culture overload. But for fans long weary of culture battles and gratuitous nostalgia, there’s not much in Ready Player One worth revisiting.