What’s the matter with Piers Morgan? Almost everything.

Yesterday, Piers Morgan published an article on the Daily Mail titled, “If black Americans want the ‘N-word’ to die, they will have to kill it themselves.” In it, Morgan voiced his opinion on what he views as a “grotesque, odious, evil stain on the English language,” citing a study recently released by the Washington Post that investigates the extensiveness of the use of the “N-word” on social media and decrying its prevalence. The use of this word, Morgan says, “has to be wrong, doesn’t it?” Morgan argues that its existence serves only to perpetuate racism. When “your average dim-witted, foul-mouthed bigot” observes black people’s use of the word, he argues, they see it as license to do the same, ensuring that, what Morgan calls in one tweet, “the lifespan of an evil word” is extended.

Rather than the word continuing to be used, Morgan argues for the following in his article: “Better, surely, to have it expunged completely. Eradicated, obliterated, tied to a literary post and whipped into such brutal submission that it never rears its vicious head again.”

It’s concerning that no editor read this piece and thought, “You know, Piers, using a whipping-post analogy and the words ‘brutal submission’ in a discussion of the ‘N-word’ and American’s legacy of slavery and racism probably isn’t the best idea.” It’s concerning that a white man felt that he was qualified—and entitled—to write a piece about what black people “have” to do in regard to a word that was invented to subjugate them. It’s concerning that Morgan even admits, “As a white man, I have no right to demand that any black person gives up using the ‘N-word’” but goes on to do just that anyway.

And it only gets more concerning when one looks at his Twitter account and the tweets that came afterwards, among them the following:

If you find my N-word column offensive or racist, then you’re part of the problem > https://t.co/3vtioEzUKX

— Piers Morgan (@piersmorgan) November 10, 2014

Ta-Nehisi Coates, renowned author, journalist, and national correspondent for the Atlantic, who recently wrote “The Case for Reparations,” was among the first of Morgan’s critics:

Morgan’s attempts to silence his critics with the above line of argument—“if you think I’m racist, then you’re the problem!”—is not only counterproductive, but it smacks of white privilege, the same white privilege that arms him with the entitlement it takes to write an article telling an oppressed group what he thinks they should do to end racism. An article leveled at white perpetuators of racism or systematic racism—one arguing against the prison industrial complex, for example, or police brutality— didn’t enter his mind; instead, the lens focuses (as it often does) on what black people are doing to “deserve” the racism of the aforementioned ignorant white bigots. Morgan acknowledges in his article that it is white people who invented the word, a “wicked derogatory insult against [black people’s] slave forebears,” but still places the onus of ending the hatred associated with it on black shoulders.

Morgan gets wrong what many “allies” get wrong—from the start of the opinion piece to the end of the tantrum on Twitter in which he defends himself from accusations of racism and white privilege—and it’s rooted in arrogance. Being aware of an issue—the contentiousness of the “N-word,” for example—does not give one license to weigh in on said issue. Our whiteness often fools us into believing that our opinion (however unqualified) matters, and social media has a way of convincing us of that myth even further. We have followers. We have people retweeting what we say. Trending topics encourage conversation about issues that may be considered out of bounds but…the Internet is for opinions!

So we plunge onward, wreaking havoc and doing damage that our privilege protects us from having to clean up. In the case of Morgan, his whiteness, maleness, and fame have combined to create a trifecta of disastrous arrogance that whispers to him, “You are the White Savior. Your time is now! Get on your white steed and save black people from themselves!”

I’ve been in his place. I’ve been the white person doing anti-racist work who sometimes gets so caught up in being part of the conversation that I don’t look down at my feet to realize I’m out of bounds. Now, in my experience with social media, there are two routes that “allies” tend to take when they find themselves out of bounds: 1) They apologize or 2) They plunge ahead, hoping that if they just run faster, they’ll find solid ground again soon.

Morgan has chosen route #2. Between last night and this morning, Morgan has retweeted dozens of people who back him up in his argument—and changed his Twitter header to a photo of himself standing between the Obamas, his display picture to a photo of himself with a group of people of color. Whether offline or online, conversations about race and racism seem to follow a very specific formula: white person accused of racism pulls out their “black friend” card, slaps it on the table. White person criticized for problematic position cites people who agree with him, never acknowledging people who don’t.

Another thing that Morgan gets wrong, not in his article, but afterwards on Twitter, is his belief that because he’s done anti-racist work in the past, he is absolved of all present and future wrongdoing. Advocating for equality for black people one time does not give one a license to talk about issues faced by oppressed groups without considering one’s own privilege. Yet Morgan tweets:

Nobody ordered me to ‘stay in your lane’ when I fought so vocally on CNN for Trayvon Martin’s right to justice.

— Piers Morgan (@piersmorgan) November 11, 2014

This is a pit that many allies fall into. Trayvon Martin had a right to justice whether Morgan or any other white person advocated for it or not: to demand gratitude (and latitude) now for doing the right thing is petulant and displays a self-centeredness that indicates Morgan’s true motivations for writing this article about the N-word to begin with: attention.

I am now trending in the United States. Read my N-word column and join the debate > https://t.co/3vtioEzUKX

— Piers Morgan (@piersmorgan) November 11, 2014

So now, Morgan, who was so concerned with the use of the “N-word” and clutched his pearls over the fact that it is used 500,000 times a day on Twitter, is now calling for one and all to join “the debate.” The debate that he, a white man with 4.28 million followers, initiated and framed around his own privileged perspective on the word. I wonder what the count for the use of the N-word on Twitter will be today, with Morgan’s blessing?

There are many reasons white people can’t say the “N-word,” and many of them align with why conversations around the existence of the N-word are out of bounds for us. Simply put: It isn’t ours. We can’t get rid of something we don’t own, and we certainly can’t demand that its owners get rid of it simply because we don’t like it. Twitter is incredible in the way that it transports users inside communities with which they might have previously had little contact. Thanks to trending topics and hashtags, with a few clicks we might find ourselves deep in the midst of cultural conversations for which we have little context, eager to join and take part in those conversations. But that doesn’t mean we should join, and we certainly shouldn’t seek to own those conversations, as Morgan has done.

The “N-word” is not white people’s to embrace or eradicate, and the discussion around its future is not ours to begin with. The conversations we can start are ones that we have license to: conversations that center our own action and the steps we can take in destroying the “grotesque, odious, evil stain” that lingers on America. Morgan and people like him demand that black people look inward and to the future; meanwhile he looks outward and to the past, failing to acknowledge the structural racism that flourishes with or without a two-syllable word. He says:

I don’t recall Martin Luther King Jr ever using the N-word.

— Piers Morgan (@piersmorgan) November 11, 2014

Maybe not. But Martin Luther King, Jr. was murdered by racists, even without the “N-word” on his lips. So what’s the real problem here?

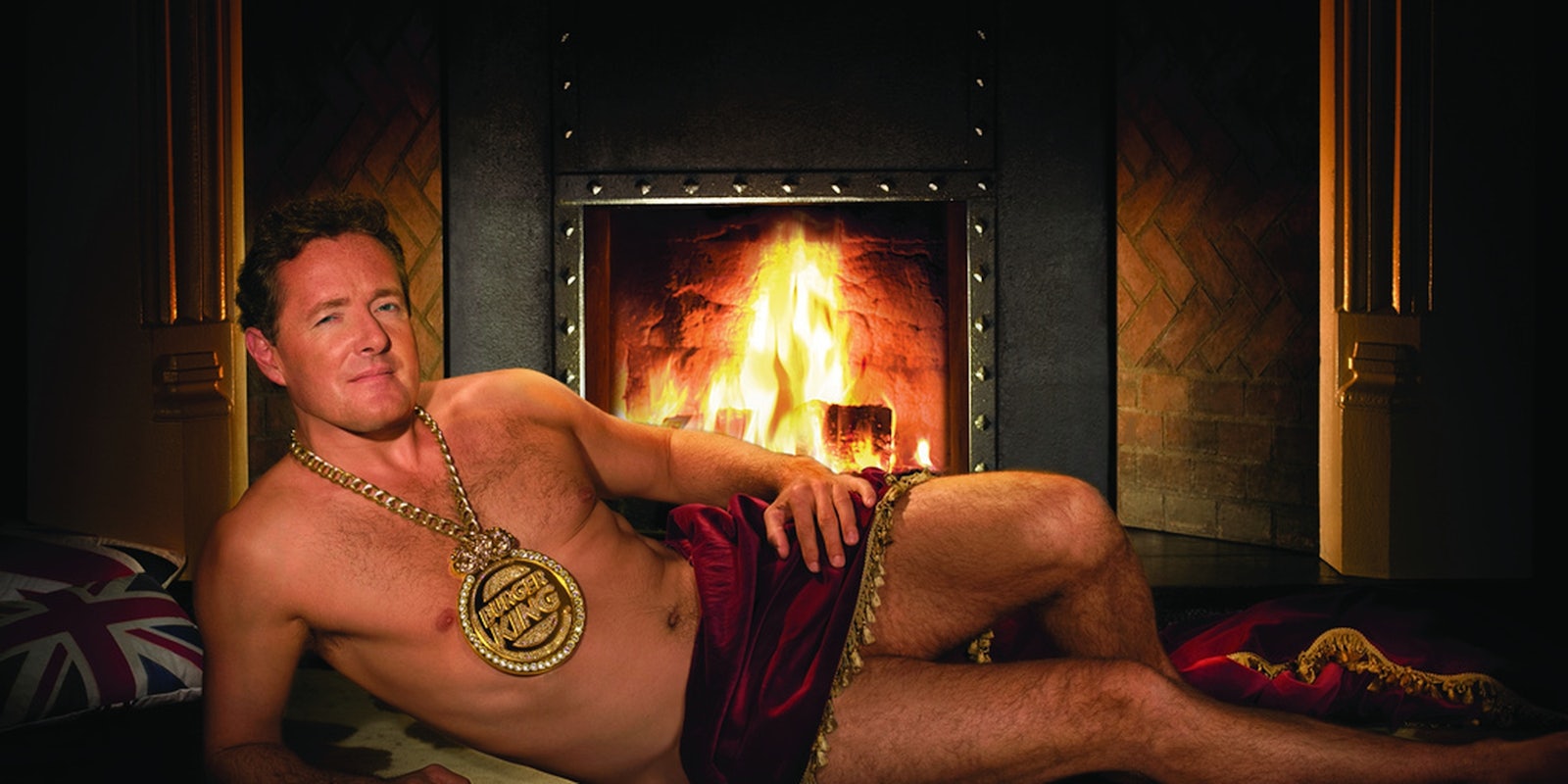

Photo via thisiscow/Flickr (CC BY N.D.-2.0)