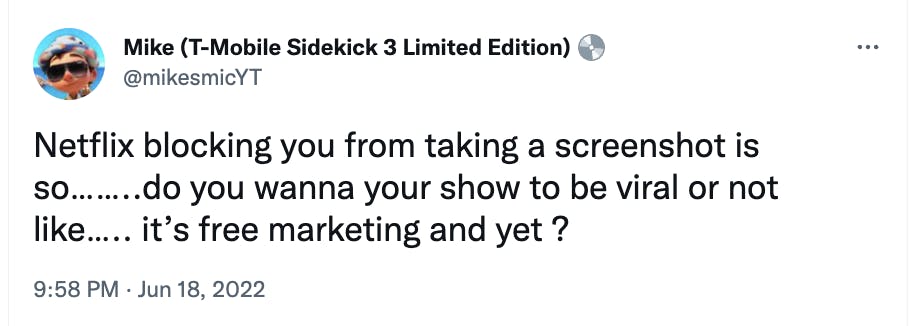

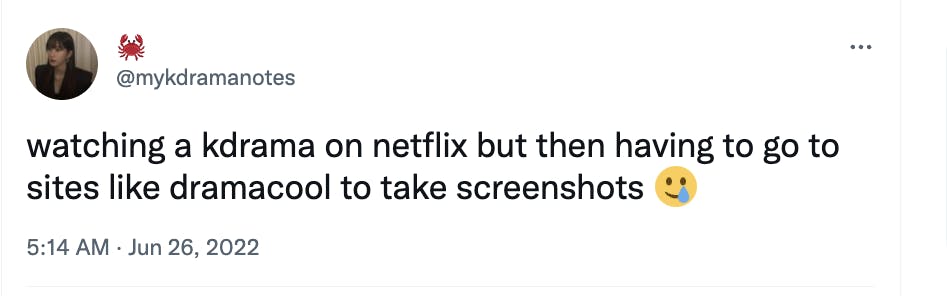

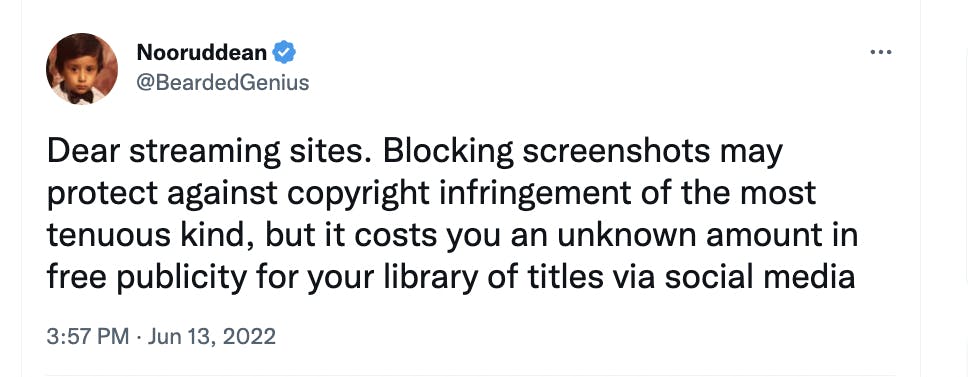

When you try to take a screenshot on Netflix, Disney+, or any of the major streaming services, you invariably end up with a blank, black screen. Automatic screenshot blocking is a point of frustration and confusion among many viewers, not least because it seems counterintuitive. When fans post screencaps on social media, they’re creating free advertising for the source material. So why are streaming services hell-bent on stopping them?

Well, despite what many subscribers believe, it’s not the streaming services blocking you from screenshotting. It’s your web browser.

Responding to an email from the Daily Dot, Netflix confirmed this wasn’t an internal decision: “Screenshot blocking happens on the browser level, and is not something we can stop or control.”

Unfortunately, this isn’t widespread knowledge, so when certain browsers tightened their Digital Rights Management (DRM) strategies in April 2022, many Netflix subscribers were quick to call out Netflix itself, accusing the platform of suddenly blocking their ability to take screenshots.

If you see people posting screenshots from Amazon, Disney+, Hulu, etc., they’re almost certainly bypassing their browser’s DRM security to do so. It’s more complicated than just hitting the screenshot button, but there are plenty of explainers out there on how to do it, typically by using third-party extensions. And judging by the vast array of Netflix screenshots and GIFs floating around social media, both browsers and streaming services are happy to turn a blind eye to this particular issue.

If you post a clandestine screenshot from, say, an unreleased Marvel movie, then the copyright holder (Disney) might request for that content to be taken down. But the streaming service Disney+ doesn’t penalize people for posting GIFs from stuff that’s already on the platform, and neither does your browser. The browser just tries to stop you making those GIFs in the first place, as part of its automated DRM technology.

What is DRM?

DRM is relevant to a wide variety of media from video games to ebooks, and it’s been controversial for years. The Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF), a non-profit digital rights organization, has criticized DRM for giving corporations too much control over media—for instance, Amazon being able to remotely delete a book from your Kindle.

Writing for the EFF in 2017, digital rights advocate Cory Doctorow emphasized the difference between old-school copyright and the more aggressive power of DRM. First off, “The reason companies want DRM has nothing to do with copyright.” That’s because “DRM law gives rightsholders more forceful, far-ranging legal powers than laws governing any other kind of technology.”

“It’s not a copyright infringement to watch Netflix in a browser that Netflix hasn’t approved,” Doctorow explains. “It’s not a copyright infringement to record a Netflix movie to watch later. It’s not a copyright infringement to feed a Netflix video to an algorithm that can warn you about upcoming strobe effects that can trigger life-threatening seizures in people with photosensitive epilepsy.”

In other words, by the old-fashioned rules of copyright, there’s no material difference between recording a show off Netflix versus doing the same on TV. But DRM law and technology are a lot more aggressive.

So while the internet theoretically gives us easier access to media, it also gives media corporations and tech companies more control over what we consume—and how. Alongside automated DMCA takedown notices, screenshot blockers are a prime example.

If you download a DRM-free video file, you can edit or screenshot it to your heart’s content. But if you’re watching something on Disney+, the situation is very different. Some streaming services will allow you to save a movie temporarily to your device, but their DRM prevents you from watching or editing it on a third-party media player. And, obviously, browsers like Safari, Chrome, and Firefox have wide-reaching digital rights management strategies that restrict your access even further.

So yes, it’s frustrating that we can’t just casually take screenshots on our phones, but this isn’t a matter of streaming services penalizing screenshots as copyright infringement. It’s a coincidental symptom of a more complicated conflict over digital rights.