Who’s better: Michael Jordan or LeBron James? Suppose you look at ESPN, NBA Twitter, NBA Instagram. Shoot, NBA anything. Among talking heads, writers, and so-called experts from my era (and before), the prevailing thought amongst those born between 1960 and 1985, principally Generation Xers, is that Jordan reigns.

Ask Skip Bayless.

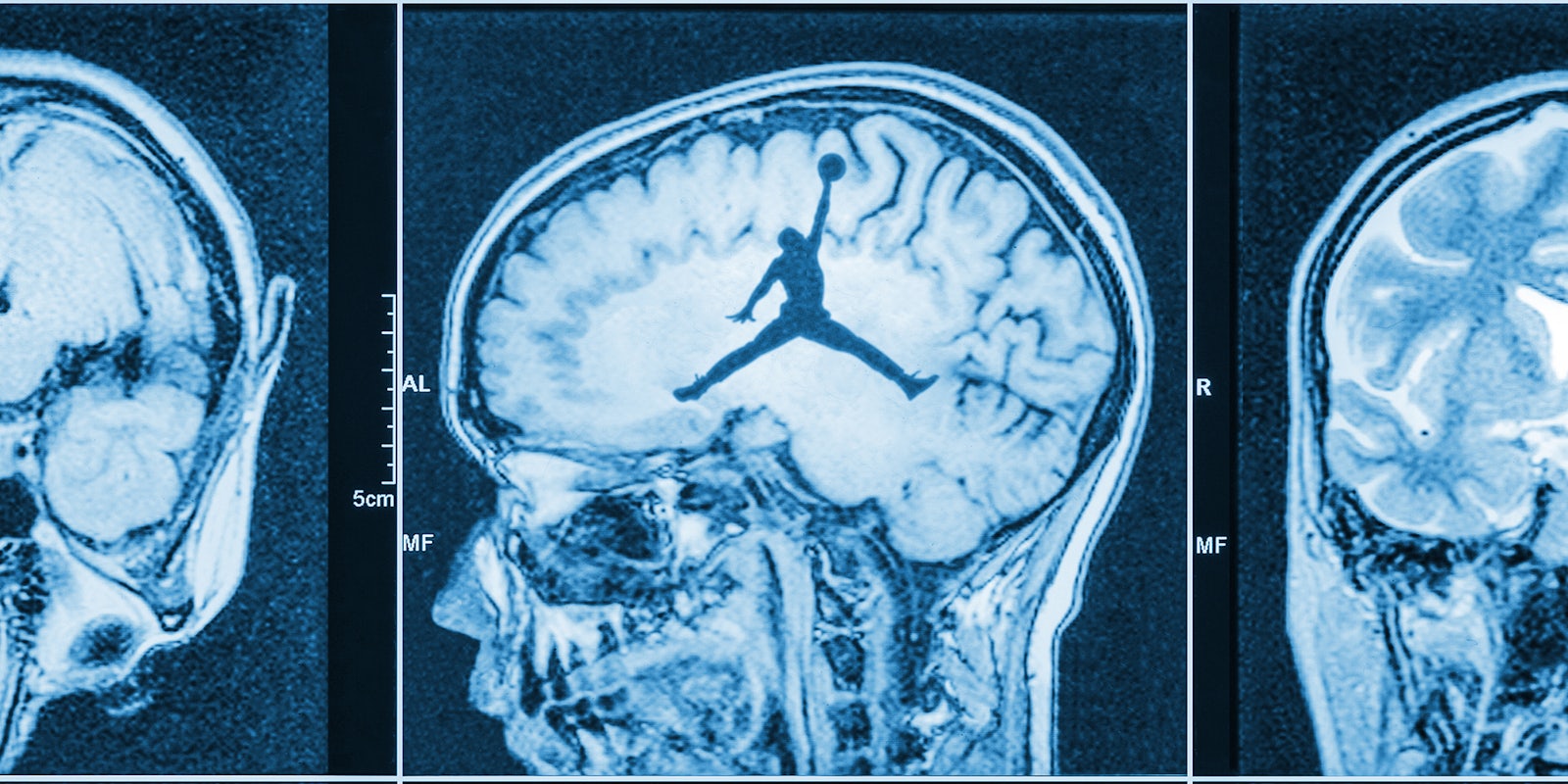

Of course, Jordan’s marketable talent was evident, even overwhelming. But how much of Jordan’s continued, seemingly untamed reign in hearts and minds was forged through Jordan’s ability to dominate his era? How much of it is Gen Xers’ collective memory and carriage of their nostalgia of the player?

More specifically, what’s the value of nostalgia created through a storytelling mechanism that has all but disappeared for any player post-Jordan? It is apparently immense, especially in the current day of NBA League Pass subscriptions and violent demystification of players’ lives.

Think back to the ’90s, back to heavily restricted player movement, Reebok Pumps, and hand-checking. Do you remember exactly how often you were able to watch literally any other team aside from the recurrent, predictable, market-based inclusions of the Knicks; Celtics; Lakers; the few teams the media built as Chicago-beaters (i.e., Utah Jazz); and the interesting NBA player de-jour, i.e., Charles Barkley, early Shaquille O’Neal, or Grant Hill?

Let’s look at this from a different lens: What if you didn’t understand precisely how Michael Jordan became imprinted into your brain, and the avenue was so inconspicuous that you’ve already forgotten it?

My live-action experience with Jordan’s all-consuming basketball greatness didn’t arrive via a Gatorade commercial, though I did “wanna be like Mike.” It wasn’t the Spike Lee-directed Nike commercials, though his product has dominated my evolving shoe collection.

It wasn’t the famed Bob Costas-hosted “NBA on NBC” telecasts, complete with John Tesh’s renowned theme, “Roundball Rock.” It wasn’t the 1992 Barcelona Olympics or a Wheaties commercial.

No, my first encounter with Jordan’s basketball ability was through a formerly semi-ubiquitous cable medium. And no, not TNT. I’m talking about WGN, or Channel 9, broadcasting live from the Chicagoland area right into a (stolen) cable box atop a 19-inch color CRT television in South Carolina, and a multitude of other markets. The channel allowed a 13-year-old in Greenville to memorize every single Chicago team, except the Bears. I knew as much or more about Frank Thomas and Mark Grace, as I did about my “hometown” Atlanta Braves, and the Atlanta Hawks to a lesser extent, who were featured on another superstation in TBS.

But having WGN meant non-Chicagoland regions across America could watch dozens of Bulls games every season. Ability aside, but also because of his ability, the proliferation of Michael Jordan offered an opportunity not provided to any other player or team, specifically during the Nineties’ heyday.

In fact, Jordan was the critical, non-boxing athlete, not only of the cable era, but of the recordable era. Given the greats immediately preceding him weren’t playing on superstations, you only saw Larry Bird or Magic Johnson regionally, or once a month (at best) via a national CBS broadcast.

By the end of Bird and Johnson’s careers, the Jordan propaganda machine was at full power. As a child, around 1990, I distinctly remember, playing seemingly endless, well-edited VHS tapes of four things at my uncle’s house: (1) essentially every championship boxing match shown on cable TV from the 160-pound weight class and up, (2) NBA Slam Dunk contests from 1985 to 1989, (3) the Jordan fluff doc Come Fly With Me, and (4) various Bulls games up to 1990.

“The thing that the advent of cable in the 1980s did is it gave people the alternative, the ability to fall somebody out of the market,” says Philip Lamar Cunningham, associate professor of media studies at Wake Forest University. “[It’s] something that I think it’s easy to overlook today because we have so many options. If you so desire, you could watch any team you want at any given time.”

The more-widely known, Atlanta-based TBS, which maverick Ted Turner openly marketed as a “superstation,” featured the Atlanta Braves as “America’s Team.” The channel also briefly put the Dominique Wilkins-led Atlanta Hawks into non-Southern living rooms, such as Cunningham’s hometown of Steubenville, Ohio. Similarly, and quiet as kept through recall of the history of our Jordan, WGN had become a regular “superstation” carried by numerous regional cable companies throughout America by the mid-’90s. The indoctrination of Michael Jordan, or rather its significant deepening, was well underway.

Generation Xers provided Jordan carriage from the cable era directly into social media, not only as a product of various brands, from the NBA, and WGN, to Nike, but also as an idea. But because he’d already been sealed in as a feeling, the broader diffusion of Jordan into digital spaces came and went without critical discussion. Therefore, LeBron James, who’d become the basketball giant of the social media age, would not be afforded the same room for mystique.

As soon as it became clear James was not a pretender but a legitimate threat to Jordan’s legacy, he became an enemy of Jordan, the player, and Jordan, the unassailable idea for an entire, still-living generation who held the world’s cultural purse-strings.

“Part of his ability to carry on as this mythic figure is due, in part, to his absence from social media,” explains Cunningham. “So we were the ones carrying water for [Jordan] to promote this ideal version of him.”

Though he owns the Charlotte Bobcats, Jordan’s primary cultural touchpoint in the present has been his ongoing relationship with Nike, which continually “retroes” popular models of yesteryear. But even Jordan as “the product” has become separated from the iconic talent in the larger non-NBA specific sphere.

Cunningham notes that the inevitable hiccup in the matrix came during his infamous 2009 Basketball Hall of Fame induction speech. Through his own doing, Jordan came across as honest and thankful but also bitter and violently petty. (He flew out a player that had made the Wilmington, North Carolina varsity high school team over him.)

Says Cunningham: “For many people, that was the first time that they had to really confront the fact that Jordan is kind of a dick, right? And that you couldn’t deny it. There were always those folks who would say, ‘Oh, well, Jordan is not quite the guy you think he is,’ right?

“But the rest of us who grew up outside of that orbit, or just engaged with him as a media-constructed being, which the NBA essentially is responsible for, that moment was difficult for us.”

However, he does see the Technicolor dream of Michael Jordan coming to an end. He says he taught a course on Black athletes in a previous semester, including to Wake Forest (high-level, NCAA Division I) basketball players.

“People who are my students’ age, the Gen Z-ers, do not know anything about Michael Jordan other than he was somebody,” he noted. “They know Michael Jordan as a name; they know he did something remarkable. [The] beginning-of-the-end of that kind of legend, I think, is already occurring because Jordan looks dated to them.”

“I showed them highlights of him winning the slam dunk contest where he takes off from the free-throw line, and for us, that was like amazing. [Generation Xers] didn’t get to see that moment replayed at our leisure until the advent of YouTube. When you look at it again, particularly in the wake of what these guys can do now, it’s actually not that impressive.”

“Circling back, I think the most significant difference now is that the institutional gatekeeping, which we found essential, [and] the ability for us to share moments, for example, has been eroding since cable.” Unbeknownst to us then, Jordan, more than any other athlete of his age, aside Mike Tyson, Bo Jackson, and Hall of Fame quarterback Joe Montana, nestled into a time where story creation would peak, which seems counterintuitive.

But the digital revolution would make story creation disposable. Investment in particular stories cheapened because of the easily created media that would follow. You didn’t have to wait a month, a week, or a day, for a new story to occupy minds. Social media took the remainder of cover away completely. But it meant Jordan would be forever locked as the first, best, and last well-recorded player with which long-form, long-range storytelling would be possible.

The questions then become straightforward: How do you build stories around people for whom you know everything? Is storytelling still useful going forward?

Cunningham recalls the league-initiated contrivance of Jordan as the NBA’s ultimate white hat, the golden knight against wickedness bathed in the league’s oft-forgotten drug era of the early 1980s: “We have to remember: the NBA is still chasing after white fans. White fans abandoned the league when it was perceived as a den of rule breakers and cocaine abusers. And Jordan gets past that. The league needed somebody to restore some form of order.”

To some extent, and similarly, James became the white hat following the infamous “Malice at the Palace” in 2004; however, the former prep-to-pro phenom wasn’t afforded the rigorous storytelling mechanism provided to Jordan, as it simply does not exist in the social media age. Jordan himself has already admitted he would have been a casualty in this era.

“For someone like myself and this is what Tiger [Woods] deals with, is that I don’t know if I could’ve survived in this Twitter time, where you don’t have the privacy that you would want, and what seems to be very innocent can always be misinterpreted,” Jordan revealed in an interview with Cigar Aficionado.

Jordan referenced Woods’ golf career, which first surged as Jordan retired from the NBA after the 1998 season. However, Woods has suffered mightily in the public eye, even through resurgent periods, with tales of his private life spilling into digital spaces. Given the fact that Jordan has “final say-so with everything that involves (his) name and likeness,” his admission is especially telling.

“Tiger played at his peak somewhere toward the end of my career. Then, what changed from that time frame to now is social media, Twitter, and all those types of things that have invaded the personalities and personal time of individuals to the point where people have been able to utilize it to their financial gains and things of that nature,” he said.

Whatever remains down the narrative-building well will have been used up by the life and death of Kobe Bryant and the looming conclusion of James’ career. Running alongside this is another truth of why Jordan’s name remains at the tips of tongues of many pre-James, pro-Jordan acolytes: Michael Jordan also represents the peak of sports narrative. Even the story around Jordan is next to impossible to beat, simply because it’s the last of its kind.

The idea of Michael Jordan was of an impossibly well-leveraged, but fast-fading, particular place and time from which the next generation is disconnected, ironically by their phones. The place long evaporated, its time has also come to an end.